Amanda Petrusich at The New Yorker:

One of my favorite Earle performances is an acoustic cover of Paul Simon’s “Graceland,” which he recorded in 2017 for Hamburger Küchensessions, a German series in which musicians perform from the corner of a kitchen. Take a breath before you watch it. His eyes are fluttering, and he appears unshaven, a little jittery. But his voice is beautiful—fragile and strong. “Graceland” is a kind of American hymn, a song about tragedy and heartache and also the part of a person’s spirit that tells them to keep going anyway, always—to atone and reclaim, as many times as it takes. Earle speeds the song up, and doesn’t quite cling to the melody or the lyrics as Simon wrote them, but his rendition is heavy, spare, and stunning. “I’m going to Graceland,” he promises, over and over as the song ends. It feels good to think that he is there right now, received and at peace.

One of my favorite Earle performances is an acoustic cover of Paul Simon’s “Graceland,” which he recorded in 2017 for Hamburger Küchensessions, a German series in which musicians perform from the corner of a kitchen. Take a breath before you watch it. His eyes are fluttering, and he appears unshaven, a little jittery. But his voice is beautiful—fragile and strong. “Graceland” is a kind of American hymn, a song about tragedy and heartache and also the part of a person’s spirit that tells them to keep going anyway, always—to atone and reclaim, as many times as it takes. Earle speeds the song up, and doesn’t quite cling to the melody or the lyrics as Simon wrote them, but his rendition is heavy, spare, and stunning. “I’m going to Graceland,” he promises, over and over as the song ends. It feels good to think that he is there right now, received and at peace.

more here.

Here is another

Here is another  In January, Robert Williams, an African-American man, was wrongfully arrested due to an inaccurate facial recognition algorithm, a computerized approach that analyzes human faces and identifies them by comparison to database images of known people. He was handcuffed and arrested in front of his family by Detroit police without being told why, then jailed overnight after the police took mugshots, fingerprints, and a DNA sample. The next day, detectives showed Williams a surveillance video image of an African-American man standing in a store that sells watches. It immediately became clear that he was not Williams. Detailing his arrest in the

In January, Robert Williams, an African-American man, was wrongfully arrested due to an inaccurate facial recognition algorithm, a computerized approach that analyzes human faces and identifies them by comparison to database images of known people. He was handcuffed and arrested in front of his family by Detroit police without being told why, then jailed overnight after the police took mugshots, fingerprints, and a DNA sample. The next day, detectives showed Williams a surveillance video image of an African-American man standing in a store that sells watches. It immediately became clear that he was not Williams. Detailing his arrest in the

Democracy imposes a substantial moral burden on citizens. They must regard one another as political equals, even when they disagree deeply about justice. Each side is likely to see the opposition as not only wrong about the issue, but on the side of injustice. How can citizens both stand up for justice and yet embrace a political arrangement that gives injustice an equal say? Political sympathy, a disposition to recognize in our opposition an attempt to live according to their conception of value, is proposed as a way to lighten democracy’s burden.

Democracy imposes a substantial moral burden on citizens. They must regard one another as political equals, even when they disagree deeply about justice. Each side is likely to see the opposition as not only wrong about the issue, but on the side of injustice. How can citizens both stand up for justice and yet embrace a political arrangement that gives injustice an equal say? Political sympathy, a disposition to recognize in our opposition an attempt to live according to their conception of value, is proposed as a way to lighten democracy’s burden. Human civilization is only a few thousand years old (depending on how we count). So if civilization will ultimately last for millions of years, it could be considered surprising that we’ve found ourselves so early in history. Should we therefore predict that human civilization will probably disappear within a few thousand years? This “Doomsday Argument” shares a family resemblance to ideas used by many professional cosmologists to judge whether a model of the universe is natural or not. Philosopher Nick Bostrom is the world’s expert on these kinds of anthropic arguments. We talk through them, leading to the biggest doozy of them all: the idea that our perceived reality might be a computer simulation being run by enormously more powerful beings.

Human civilization is only a few thousand years old (depending on how we count). So if civilization will ultimately last for millions of years, it could be considered surprising that we’ve found ourselves so early in history. Should we therefore predict that human civilization will probably disappear within a few thousand years? This “Doomsday Argument” shares a family resemblance to ideas used by many professional cosmologists to judge whether a model of the universe is natural or not. Philosopher Nick Bostrom is the world’s expert on these kinds of anthropic arguments. We talk through them, leading to the biggest doozy of them all: the idea that our perceived reality might be a computer simulation being run by enormously more powerful beings. “One way the internet distorts our picture of ourselves is by feeding the human tendency to overestimate our knowledge of how the world works,”

“One way the internet distorts our picture of ourselves is by feeding the human tendency to overestimate our knowledge of how the world works,”  At it

At it

There’s a trope of the British Asian identity narrative, once captured with such originality and brilliance in Hanif Kureishi’s

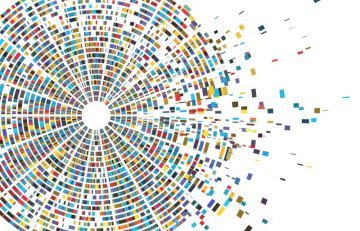

There’s a trope of the British Asian identity narrative, once captured with such originality and brilliance in Hanif Kureishi’s  With the refinement and reduced cost of sequencing technology, science has reached another inflection point: population-scale genomics, where clinical-grade assays can be used to advance healthcare, while fueling research. The Healthy Nevada Project (HNP) epitomizes that movement. A population health initiative run by the Renown Institute for Health Innovation (Renown IHI), a partnership between Renown Health and the Desert Research Institute, the project aims to combine genomic, environmental and medical data from 250,000 participants to assess the influence of genetics on health and disease. The study also uses sequencing data to screen participants for medically actionable genetic conditions, such as familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC), and Lynch syndrome (LS).

With the refinement and reduced cost of sequencing technology, science has reached another inflection point: population-scale genomics, where clinical-grade assays can be used to advance healthcare, while fueling research. The Healthy Nevada Project (HNP) epitomizes that movement. A population health initiative run by the Renown Institute for Health Innovation (Renown IHI), a partnership between Renown Health and the Desert Research Institute, the project aims to combine genomic, environmental and medical data from 250,000 participants to assess the influence of genetics on health and disease. The study also uses sequencing data to screen participants for medically actionable genetic conditions, such as familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC), and Lynch syndrome (LS).

first their concerted honks—

first their concerted honks—