Stefan Collini in the London Review of Books:

I hadn’t been expecting to bump into Frank in one of the remoter stacks of the Cambridge University Library. This is where they keep the back numbers of old scholarly periodicals, a morgue only likely to be violated by those, like me, who now spend their days picking over the cairns left by academic labourers seventy years ago. And Frank Kermode had been dead for almost ten years – he died on 17 August 2010. I’d seen him in my mind quite frequently in the intervening decade: one of my running routes takes me past his old flat, and the sight of the building is enough to stir memories of evenings spent drinking and talking. But this was different. One might expect to meet any number of those who navvied at Eng. Lit. in the first half of the 20th century here, names now largely unknown even to their successors. But, quite suddenly, as I was looking for something else in the back pages of the impeccably learned (read: dry as dust) Review of English Studies for July 1949, there he was: ‘Frank Kermode’. Not, I was interested to note, ‘J.F. Kermode’ or any other variant that signalled the first name he never used. (It was one of the lesser indignities of his time in hospital during his final illness that well-meaning nurses and auxiliaries, scanning his patient details, would cheerily address him as ‘John’.) He was already using the name that was to become so familiar, the byline that launched a thousand pieces. Was he already that ‘Frank Kermode’, that effortlessly elegant, perceptive, slyly amusing, wide-ranging critic? Not really, not to judge by this piece of scholarly flotsam. It was a review of a book called Music and Poetry of the English Renaissance by Bruce Pattison: a learned, exact, even exacting, piece, full of abstruse detail, acknowledging the book’s achievement but, in the manner of young scholars everywhere, ticking it off for not drawing on the latest scholarship.

More here.

When Don Lyons, director of the Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program visited a small inland valley in Japan, he found a local variety of rice colloquially called “cormorant rice.” The grain got its moniker not from its size or color or area of origin, but from the

When Don Lyons, director of the Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program visited a small inland valley in Japan, he found a local variety of rice colloquially called “cormorant rice.” The grain got its moniker not from its size or color or area of origin, but from the

Early in the coronavirus pandemic, a

Early in the coronavirus pandemic, a  Elena Ferrante

Elena Ferrante Nearly 60 years ago, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist Eugene Wigner captured one of the many oddities of quantum mechanics in a thought experiment. He imagined a friend of his, sealed in a lab, measuring a particle such as an atom while Wigner stood outside. Quantum mechanics famously allows particles to occupy many locations at once—a so-called superposition—but the friend’s observation “collapses” the particle to just one spot. Yet for Wigner, the superposition remains: The collapse occurs only when he makes a measurement sometime later. Worse, Wigner also sees the friend in a superposition. Their experiences directly conflict.

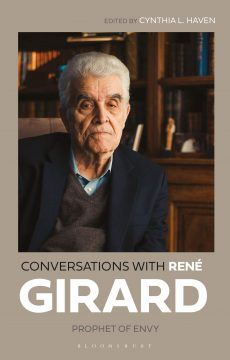

Nearly 60 years ago, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist Eugene Wigner captured one of the many oddities of quantum mechanics in a thought experiment. He imagined a friend of his, sealed in a lab, measuring a particle such as an atom while Wigner stood outside. Quantum mechanics famously allows particles to occupy many locations at once—a so-called superposition—but the friend’s observation “collapses” the particle to just one spot. Yet for Wigner, the superposition remains: The collapse occurs only when he makes a measurement sometime later. Worse, Wigner also sees the friend in a superposition. Their experiences directly conflict. IN 1953, ISAIAH BERLIN published his long essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” outlining his now-famous Oxbridge variant on there are two kinds of people in this world. He drew the title from an ambiguous fragment attributed to the ancient lyric poet Archilochus of Paros: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing.” Written with the aim of pointing out tensions between Tolstoy’s grand view of history and the artistic temperament that saw such a view as untenable, Berlin’s essay became an unlikely hit, although less for its argument about Russian literature than for its contention that two antithetical personae govern the world of ideas: hedgehogs, who view the world in terms of some all-embracing system, seeing all facts as fitting into a grand pattern; and foxes, those pluralists or particularists who refuse “big theory” for reasons either intellectual or temperamental.

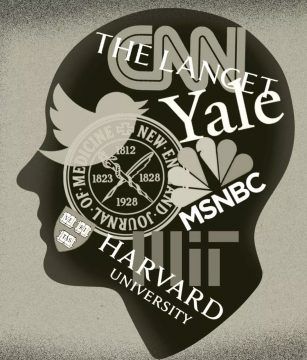

IN 1953, ISAIAH BERLIN published his long essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” outlining his now-famous Oxbridge variant on there are two kinds of people in this world. He drew the title from an ambiguous fragment attributed to the ancient lyric poet Archilochus of Paros: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing.” Written with the aim of pointing out tensions between Tolstoy’s grand view of history and the artistic temperament that saw such a view as untenable, Berlin’s essay became an unlikely hit, although less for its argument about Russian literature than for its contention that two antithetical personae govern the world of ideas: hedgehogs, who view the world in terms of some all-embracing system, seeing all facts as fitting into a grand pattern; and foxes, those pluralists or particularists who refuse “big theory” for reasons either intellectual or temperamental. Physicists have traditionally simplified systems as much as possible, in order to shed light on fundamental properties. But small, simple parts build up into large, complex wholes. Are there new rules and laws of nature that apply specifically to the realm of complexity? This has been a popular question for a few decades now, and we have some answers but not as many as we would like. Neil Johnson is an expert on complex systems generally, and information networks in particular. We discuss how self-organization can arise from individual units following their own agendas, and how we can mathematically characterize such behavior. Then we talk about information networks in the modern world, including how they have been used to spread disinformation and find recruits for radical fringe groups.

Physicists have traditionally simplified systems as much as possible, in order to shed light on fundamental properties. But small, simple parts build up into large, complex wholes. Are there new rules and laws of nature that apply specifically to the realm of complexity? This has been a popular question for a few decades now, and we have some answers but not as many as we would like. Neil Johnson is an expert on complex systems generally, and information networks in particular. We discuss how self-organization can arise from individual units following their own agendas, and how we can mathematically characterize such behavior. Then we talk about information networks in the modern world, including how they have been used to spread disinformation and find recruits for radical fringe groups. A first-hand account of Britain’s role in the 1953 coup that overthrew the elected prime minister of

A first-hand account of Britain’s role in the 1953 coup that overthrew the elected prime minister of  That the Latin name for the caper flower, Capparis spinosa, is related to the Italian word capriolare (meaning ‘to jump in the air’), is a droll enough visual/verbal play to suggest that Titian is intentionally teasing us with the placement of the prickly perennial plant directly under the bouncing Bacchus. But it is the plant’s medicinal use, since antiquity, as a natural carminative (or remedy for excessive flatulence) that reveals the artist is truly letting rip with some mischievous fun. In the context of Titian’s carefully deployed caper, Bacchus’s explosive propulsion from his seat appears more wittily, if crudely, choreographed by Titian, who demystifies the lovestruck levitation by providing us with a more down-to-earth explanation for the cheeky lift-off. In Titian’s retelling of Ovid’s myth, Bacchus has been hoisted by his own pungent petard, as Shakespeare, who likewise loved toilet humour, might have said.

That the Latin name for the caper flower, Capparis spinosa, is related to the Italian word capriolare (meaning ‘to jump in the air’), is a droll enough visual/verbal play to suggest that Titian is intentionally teasing us with the placement of the prickly perennial plant directly under the bouncing Bacchus. But it is the plant’s medicinal use, since antiquity, as a natural carminative (or remedy for excessive flatulence) that reveals the artist is truly letting rip with some mischievous fun. In the context of Titian’s carefully deployed caper, Bacchus’s explosive propulsion from his seat appears more wittily, if crudely, choreographed by Titian, who demystifies the lovestruck levitation by providing us with a more down-to-earth explanation for the cheeky lift-off. In Titian’s retelling of Ovid’s myth, Bacchus has been hoisted by his own pungent petard, as Shakespeare, who likewise loved toilet humour, might have said. The original Garden of Emptiness, Kyle Chayka explains in his pugnacious whistlestop tour of minimalism, is to be found in the 16th-century rock garden of the Kyoto Zen temple Ryoan-Ji. Chayka journeys to this sacred spot in search of the philosophical minimalism that has been obscured by today’s commodified decluttering. His book, which ranges from the Stoics and Buddhism to Mies van der Rohe, is a rebuke to the Shintoistic declutterer Marie Kondo, whose bestselling Netflix-powered KonMari method urges us to retain only those possessions that ‘spark joy’ and to practise such techniques as folding trousers vertically and not – heavens! – horizontally. Chayka warms to Donald Judd’s Plexiglas, Philip Johnson’s Glass House and Brian Eno’s ‘Discreet Music’. He is irked by minimalist hipsters’ all-grey uniforms and the solipsistic sensory deprivation of the Soulex company’s amniotic ‘float spas’. But such businesses are booming. In hard times, many go minimal by default, yet others pay handsomely for the ultimate postmodern lifestyle commodity, which, Kayla observes, they can of course never possess: nothing.

The original Garden of Emptiness, Kyle Chayka explains in his pugnacious whistlestop tour of minimalism, is to be found in the 16th-century rock garden of the Kyoto Zen temple Ryoan-Ji. Chayka journeys to this sacred spot in search of the philosophical minimalism that has been obscured by today’s commodified decluttering. His book, which ranges from the Stoics and Buddhism to Mies van der Rohe, is a rebuke to the Shintoistic declutterer Marie Kondo, whose bestselling Netflix-powered KonMari method urges us to retain only those possessions that ‘spark joy’ and to practise such techniques as folding trousers vertically and not – heavens! – horizontally. Chayka warms to Donald Judd’s Plexiglas, Philip Johnson’s Glass House and Brian Eno’s ‘Discreet Music’. He is irked by minimalist hipsters’ all-grey uniforms and the solipsistic sensory deprivation of the Soulex company’s amniotic ‘float spas’. But such businesses are booming. In hard times, many go minimal by default, yet others pay handsomely for the ultimate postmodern lifestyle commodity, which, Kayla observes, they can of course never possess: nothing. In 1994, the term ‘straight to TV movie’ was used mostly as an insult. So when a small film called The Last Seduction premiered on HBO, nobody expected much. But those who caught it were floored by a darkly comic noir thriller with a knockout performance from Linda Fiorentino as Bridget Gregory. Bridget is a smart-talking New Yorker who hits ‘cow country’ with a suitcase of cash her husband Clay (Bill Pullman) had acquired in a drug deal. Advised to lie low for a while, Bridget shacks up with smitten local Mike (Peter Berg) and uses him to enact a devious plan. Directed by John Dahl and written by Steve Barancik, The Last Seduction is bitterly funny and deliciously clever – the razor-sharp dialogue is loaded with one-liners. It’s also sexy in a way that appeals to both women and men. With its manipulative femme fatale, it touches on similar themes to the big-budget Basic Instinct – but many believe it does it much better.

In 1994, the term ‘straight to TV movie’ was used mostly as an insult. So when a small film called The Last Seduction premiered on HBO, nobody expected much. But those who caught it were floored by a darkly comic noir thriller with a knockout performance from Linda Fiorentino as Bridget Gregory. Bridget is a smart-talking New Yorker who hits ‘cow country’ with a suitcase of cash her husband Clay (Bill Pullman) had acquired in a drug deal. Advised to lie low for a while, Bridget shacks up with smitten local Mike (Peter Berg) and uses him to enact a devious plan. Directed by John Dahl and written by Steve Barancik, The Last Seduction is bitterly funny and deliciously clever – the razor-sharp dialogue is loaded with one-liners. It’s also sexy in a way that appeals to both women and men. With its manipulative femme fatale, it touches on similar themes to the big-budget Basic Instinct – but many believe it does it much better. Soon after the Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan

Soon after the Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan  Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.

Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.