John Warner in Inside Higher Ed:

In 1965, James Baldwin debated William F. Buckley at the Cambridge Union Society, Cambridge University. The topic of the debate was, “The American Dream is at the expense of the American negro.”

In 1965, James Baldwin debated William F. Buckley at the Cambridge Union Society, Cambridge University. The topic of the debate was, “The American Dream is at the expense of the American negro.”

…Baldwin delivers his remarks slowly, somehow seeming both passionate and cool, like jazz. He is mesmerizing, as shown by the camera cutaways to the audience that sits rapt. It almost seems unfair, a distortion, to excerpt Baldwin’s remarks because as a work of rhetoric, it surpasses even the best of Martin Luther King or JFK. In the opening, he acknowledges the trap of segregation for the segregationists, that what he is discussing is a fundamental inequality born of an unjust system in which individuals are only actors:

“The white South African or Mississippi sharecropper or Alabama sheriff has at bottom a system of reality which compels them really to believe when they face the Negro that this woman, this man, this child must be insane to attack the system to which he owes his entire identity.”

He then makes deft use of the 2nd person in order to draw a circle around the experience of being black in 1960s America:

“In the case of the American Negro, from the moment you are born every stick and stone, every face, is white. Since you have not yet seen a mirror, you suppose you are, too. It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, 6, or 7 to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to see Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, and although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you.”

A small ripple of laughter coursed through the Cambridge fellows at that moment. A laugh not of amusement, but recognition. Baldwin shifts to the first person, reminding the audience that the man in front of them is indeed part of this “you”:

“From a very literal point of view, the harbors and the ports and the railroads of the country–the economy, especially in the South–could not conceivably be what they are if it had not been (and this is still so) for cheap labor. I am speaking very seriously, and this is not an overstatement: I picked cotton, I carried it to the market, I built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing. For nothing.”

The Southern oligarchy which has still today so very much power in Washington, and therefore some power in the world, was created by my labor and my sweat and the violation of my women and the murder of my children. This in the land of the free, the home of the brave.”

Baldwin hammers the “I” in his delivery in the first part. The final lines of this passage are delivered in some combination of sorrow and disbelief. Baldwin then returns to his theme that black America is not the only group being destroyed by this system:

“Sheriff Clark in Selma, Ala., cannot be dismissed as a total monster; I am sure he loves his wife and children and likes to get drunk. One has to assume that he is a man like me. But he does not know what drives him to use the club, to menace with the gun and to use the cattle prod. Something awful must have happened to a human being to be able to put a cattle prod against a woman’s breasts. What happens to the woman is ghastly. What happens to the man who does it is in some ways much, much worse. Their moral lives have been destroyed by the plague called color.”

Baldwin finishes with this:

“It is a terrible thing for an entire people to surrender to the notion that one-ninth of its population is beneath them. Until the moment comes when we, the Americans, are able to accept the fact that my ancestors are both black and white, that on that continent we are trying to forge a new identity, that we need each other, that I am not a ward of America, I am not an object of missionary charity, I am one of the people who built the country–until this moment comes there is scarcely any hope for the American dream. If the people are denied participation in it, by their very presence they will wreck it. And if that happens it is a very grave moment for the West.”

Baldwin received a standing ovation from the very white, very British audience. The announcer says in the video that he’s never seen such a reaction at these events before.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will honor The Black History Month. This year’s theme is “African Americans and the Vote.” Readers are encouraged to send in their suggestions)

When Alexa replied to my question about the weather by tacking on ‘Have a nice day,’ I immediately shot back ‘You too,’ and then stared into space, slightly embarrassed. I also found myself spontaneously shouting words of encouragement to ‘Robbie’ my Roomba vacuum as I saw him passing down the hallway. And recently in Berkeley, California, a group of us on the sidewalk gathered around a cute four-wheeled KiwiBot – an autonomous food-delivery robot waiting for the traffic light to change. Some of us instinctively started talking to it in the sing-song voice you might use with a dog or a baby: ‘Who’s a good boy?’

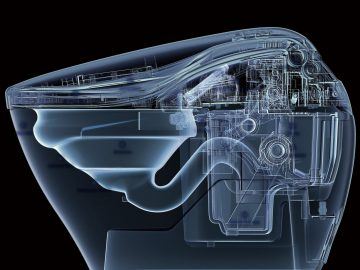

When Alexa replied to my question about the weather by tacking on ‘Have a nice day,’ I immediately shot back ‘You too,’ and then stared into space, slightly embarrassed. I also found myself spontaneously shouting words of encouragement to ‘Robbie’ my Roomba vacuum as I saw him passing down the hallway. And recently in Berkeley, California, a group of us on the sidewalk gathered around a cute four-wheeled KiwiBot – an autonomous food-delivery robot waiting for the traffic light to change. Some of us instinctively started talking to it in the sing-song voice you might use with a dog or a baby: ‘Who’s a good boy?’ Japanese toilets are marvels of technological innovation. They have integrated bidets, which squirt water to clean your private parts. They have dryers and heated seats. They use water efficiently, clean themselves and deodorize the air, so bathrooms actually smell good. They have white noise machines, so you can fill your stall with the sound of rain for relaxation and privacy. Some even have built-in night lights and music players. It’s all customizable and controlled by electronic buttons on a panel next to your seat.

Japanese toilets are marvels of technological innovation. They have integrated bidets, which squirt water to clean your private parts. They have dryers and heated seats. They use water efficiently, clean themselves and deodorize the air, so bathrooms actually smell good. They have white noise machines, so you can fill your stall with the sound of rain for relaxation and privacy. Some even have built-in night lights and music players. It’s all customizable and controlled by electronic buttons on a panel next to your seat. ‘Hate is a poison that… is responsible for far too many crimes’,

‘Hate is a poison that… is responsible for far too many crimes’,  Unfinished Business does not present as a work of literary criticism per se. While it is concerned with interpretation and meaning, its fundamental focus is on that most peculiar of phenomena, the way that texts appear to change as we reread them throughout our lives. The texts, of course, do no such thing; we’re the ones doing the changing, and this relatively banal truth is Gornick’s entry point, using select works to illustrate the effects of lived life as measured against the yardstick of that relatively stable artifact, the book. In this context, the books and authors Gornick treats are largely irrelevant: Gornick has selected them for the glimpse each provides of the reexaminations of herself and her mind that her rereadings have prompted, or that have prompted the rereadings. I note this because I need to confess my own unfamiliarity with many of the books she writes about; my own experience of Unfinished Business didn’t suffer on account of my ignorance.

Unfinished Business does not present as a work of literary criticism per se. While it is concerned with interpretation and meaning, its fundamental focus is on that most peculiar of phenomena, the way that texts appear to change as we reread them throughout our lives. The texts, of course, do no such thing; we’re the ones doing the changing, and this relatively banal truth is Gornick’s entry point, using select works to illustrate the effects of lived life as measured against the yardstick of that relatively stable artifact, the book. In this context, the books and authors Gornick treats are largely irrelevant: Gornick has selected them for the glimpse each provides of the reexaminations of herself and her mind that her rereadings have prompted, or that have prompted the rereadings. I note this because I need to confess my own unfamiliarity with many of the books she writes about; my own experience of Unfinished Business didn’t suffer on account of my ignorance. It was driven home to me repeatedly in my early efforts to build an investment strategy that, quite apart from the question of whether the quest for wealth is sinful in the sense understood by the painters of vanitas scenes, it is most certainly and irredeemably unethical. All of the relatively low-risk index funds that are the bedrock of a sound investment portfolio are spread across so many different kinds of companies that one could not possibly keep track of all the ways each of them violates the rights and sanctity of its employees, of its customers, of the environment. And even if you are investing in individual companies (while maintaining healthy risk-buffering diversification, etc.), you must accept that the only way for you as a shareholder to get ahead is for those companies to continue to grow, even when the limits of whatever good they might do for the world, assuming they were doing good for the world to begin with, have been surpassed. That is just how capitalism works: an unceasing imperative for growth beyond any natural necessity, leading to the desolation of the earth and the exhaustion of its resources. I am a part of that now, too. I always was, to some extent, with every purchase I made, every light switch I flipped. But to become an active investor is to make it official, to solemnify the contract, as if in blood.

It was driven home to me repeatedly in my early efforts to build an investment strategy that, quite apart from the question of whether the quest for wealth is sinful in the sense understood by the painters of vanitas scenes, it is most certainly and irredeemably unethical. All of the relatively low-risk index funds that are the bedrock of a sound investment portfolio are spread across so many different kinds of companies that one could not possibly keep track of all the ways each of them violates the rights and sanctity of its employees, of its customers, of the environment. And even if you are investing in individual companies (while maintaining healthy risk-buffering diversification, etc.), you must accept that the only way for you as a shareholder to get ahead is for those companies to continue to grow, even when the limits of whatever good they might do for the world, assuming they were doing good for the world to begin with, have been surpassed. That is just how capitalism works: an unceasing imperative for growth beyond any natural necessity, leading to the desolation of the earth and the exhaustion of its resources. I am a part of that now, too. I always was, to some extent, with every purchase I made, every light switch I flipped. But to become an active investor is to make it official, to solemnify the contract, as if in blood. Lamenting

Lamenting  As the global tide of populism challenges the very idea of liberal democracy, Donald Trump’s visit to India highlighted how Trump and India’s prime minister,

As the global tide of populism challenges the very idea of liberal democracy, Donald Trump’s visit to India highlighted how Trump and India’s prime minister,  By the time the British artist Isaac Julien’s iconic short essay-film “Looking for Langston” was released, in 1989, Julien’s ostensible subject, the enigmatic poet and race man Langston Hughes, had been dead for twenty-two years, but the search for his “real” story was still ongoing. There was a sense—particularly among gay men of color, like Julien, who had so few “out” ancestors and wanted to claim the prolific, uneven, but significant writer as one of their own—that some essential things about Hughes had been obscured or disfigured in his work and his memoirs. Born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, and transplanted to New York City as a strikingly handsome nineteen-year-old, Hughes became, with the publication of his first book of poems, “The Weary Blues” (1926), a prominent New Negro: modern, pluralistic in his beliefs, and a member of what the folklorist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston called “the niggerati,” a loosely formed alliance of black writers and intellectuals that included Hurston, the author and diplomat James Weldon Johnson, the openly gay poet and artist Richard Bruce Nugent, and the novelists Nella Larsen, Jessie Fauset, and Wallace Thurman (whose 1929 novel about color fixation among blacks, “The Blacker the Berry,” conveys some of the energy of the time).

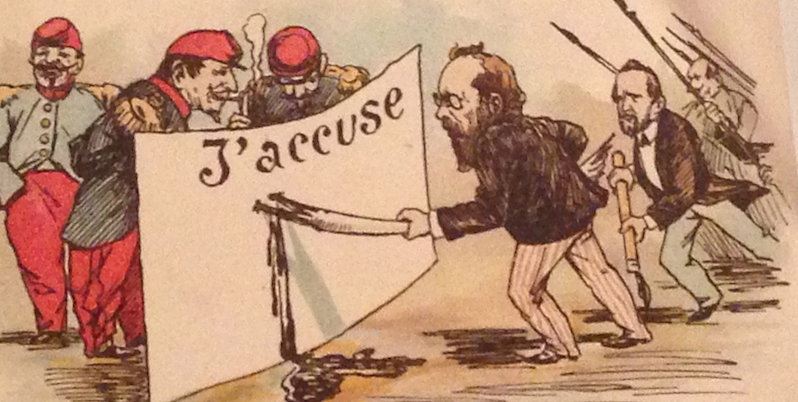

By the time the British artist Isaac Julien’s iconic short essay-film “Looking for Langston” was released, in 1989, Julien’s ostensible subject, the enigmatic poet and race man Langston Hughes, had been dead for twenty-two years, but the search for his “real” story was still ongoing. There was a sense—particularly among gay men of color, like Julien, who had so few “out” ancestors and wanted to claim the prolific, uneven, but significant writer as one of their own—that some essential things about Hughes had been obscured or disfigured in his work and his memoirs. Born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, and transplanted to New York City as a strikingly handsome nineteen-year-old, Hughes became, with the publication of his first book of poems, “The Weary Blues” (1926), a prominent New Negro: modern, pluralistic in his beliefs, and a member of what the folklorist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston called “the niggerati,” a loosely formed alliance of black writers and intellectuals that included Hurston, the author and diplomat James Weldon Johnson, the openly gay poet and artist Richard Bruce Nugent, and the novelists Nella Larsen, Jessie Fauset, and Wallace Thurman (whose 1929 novel about color fixation among blacks, “The Blacker the Berry,” conveys some of the energy of the time). Merrie England, the Golden Age, la Belle Epoque: such shiny brand names are always coined retrospectively. No one in Paris ever said to one another, in 1895 or 1900, “We’re living in the Belle Epoque, better make the most of it.” The phrase describing that time of peace between the catastrophic French defeat of 1870–71 and the catastrophic French victory of 1914–18 didn’t come into the language until 1940–41, after another French defeat. It was the title of a radio program which morphed into a live musical-theater show: a feel-good coinage and a feel-good distraction which also played up to certain German preconceptions about oh-la-la, can-can France.

Merrie England, the Golden Age, la Belle Epoque: such shiny brand names are always coined retrospectively. No one in Paris ever said to one another, in 1895 or 1900, “We’re living in the Belle Epoque, better make the most of it.” The phrase describing that time of peace between the catastrophic French defeat of 1870–71 and the catastrophic French victory of 1914–18 didn’t come into the language until 1940–41, after another French defeat. It was the title of a radio program which morphed into a live musical-theater show: a feel-good coinage and a feel-good distraction which also played up to certain German preconceptions about oh-la-la, can-can France.

A newly identified coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (formerly 2019-nCoV) has been spreading in China, and has now reached multiple other countries. Here’s what you need to know about the virus and the disease it causes, called COVID-19.

A newly identified coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (formerly 2019-nCoV) has been spreading in China, and has now reached multiple other countries. Here’s what you need to know about the virus and the disease it causes, called COVID-19. BREATHING FINE PARTICLES

BREATHING FINE PARTICLES Pádraig: Well, I think that language used well becomes its own scripture. And we’re in need of all kinds of new scriptures. In poetry, there is an attempt to create a scripture that’s sufficient for the moment. But for the poet, and for anybody that’s reading that poet’s work, there is a recognition to say, “These words haven’t been put in the right way for me yet, so therefore I’m going to do it myself, or I’m going to read around to see who has done it.” And that that can bless the human experience and also create the human experience. By feeling created and validated, to be made—to be truthed into being (valid comes from the French for truth)—to have the deepest part of ourselves recognized, there is something sacramental in that whether or not you’re a person of religion. There’s something saving in it whether or not you’re a person of religion. It brings you into the possibility of thinking: “There’s agency here.”

Pádraig: Well, I think that language used well becomes its own scripture. And we’re in need of all kinds of new scriptures. In poetry, there is an attempt to create a scripture that’s sufficient for the moment. But for the poet, and for anybody that’s reading that poet’s work, there is a recognition to say, “These words haven’t been put in the right way for me yet, so therefore I’m going to do it myself, or I’m going to read around to see who has done it.” And that that can bless the human experience and also create the human experience. By feeling created and validated, to be made—to be truthed into being (valid comes from the French for truth)—to have the deepest part of ourselves recognized, there is something sacramental in that whether or not you’re a person of religion. There’s something saving in it whether or not you’re a person of religion. It brings you into the possibility of thinking: “There’s agency here.” The temptation to read Piglia’s books as straightforward journals—despite the author’s insistence on treating them as fiction—can occasionally be maddening, as if their readers have been unwittingly enlisted in a postmodern game. And indeed we have, though much more is at stake. As Piglia witnessed the dissolution of Argentine society under a series of repressive governments, he sought new models of writing and representing reality. In metafiction, he found a means to subvert the conformity and censorship that flourished under these regimes. While he rejected the idea that fictional “coding” was possible only when living and writing under a restrictive government, he believed, as he told an interviewer, that “political contexts define ways of reading.” Through indirection and other literary techniques, Piglia revealed the frightening mechanisms of state power that had subjugated Argentina and the ways in which they might be resisted.

The temptation to read Piglia’s books as straightforward journals—despite the author’s insistence on treating them as fiction—can occasionally be maddening, as if their readers have been unwittingly enlisted in a postmodern game. And indeed we have, though much more is at stake. As Piglia witnessed the dissolution of Argentine society under a series of repressive governments, he sought new models of writing and representing reality. In metafiction, he found a means to subvert the conformity and censorship that flourished under these regimes. While he rejected the idea that fictional “coding” was possible only when living and writing under a restrictive government, he believed, as he told an interviewer, that “political contexts define ways of reading.” Through indirection and other literary techniques, Piglia revealed the frightening mechanisms of state power that had subjugated Argentina and the ways in which they might be resisted. Unlike much that was extracted from India, these paintings were not plunder, and those who created them were properly remunerated and often received due credit for their work. When annotating the paintings of birds and animals she commissioned, Lady Impey, wife of the chief justice of the Supreme Court in Calcutta, left a space for the artists’ names to be inscribed in Persian. Similarly, the outstanding studies of animals commissioned between 1795 and 1818 by the surgeon Francis Buchanan bear the inscription ‘Haludar Pinxt’, which means that this Bengali artist became known in Europe during his lifetime. Indeed, his image of an Indian Sambar deer, sent to the Company’s library in Leadenhall Street in 1808, was cited at the time in French and German scientific journals precisely because it had been ‘painted on the spot’ and provided the first accurate record of the animal’s appearance. It was also, like many of these paintings, a work of art in its own right, a perfect example of the fruitful confluence of European science and Indian sensibility.

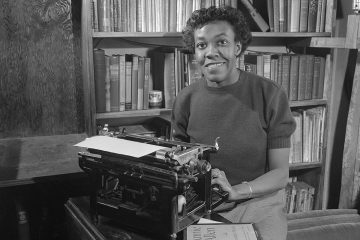

Unlike much that was extracted from India, these paintings were not plunder, and those who created them were properly remunerated and often received due credit for their work. When annotating the paintings of birds and animals she commissioned, Lady Impey, wife of the chief justice of the Supreme Court in Calcutta, left a space for the artists’ names to be inscribed in Persian. Similarly, the outstanding studies of animals commissioned between 1795 and 1818 by the surgeon Francis Buchanan bear the inscription ‘Haludar Pinxt’, which means that this Bengali artist became known in Europe during his lifetime. Indeed, his image of an Indian Sambar deer, sent to the Company’s library in Leadenhall Street in 1808, was cited at the time in French and German scientific journals precisely because it had been ‘painted on the spot’ and provided the first accurate record of the animal’s appearance. It was also, like many of these paintings, a work of art in its own right, a perfect example of the fruitful confluence of European science and Indian sensibility. The opening lines of Gwendolyn Brooks’s epic “The Anniad” are, like the rest of the poem, deceptively uncomplicated. “Think of sweet and chocolate,” she writes:

The opening lines of Gwendolyn Brooks’s epic “The Anniad” are, like the rest of the poem, deceptively uncomplicated. “Think of sweet and chocolate,” she writes: