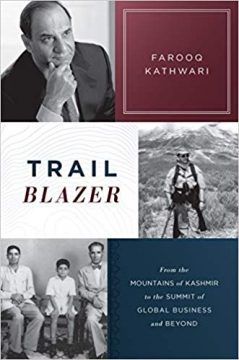

by Rafiq Kathwari

A Jewish grandfather and a Muslim man walk into a New York delicatessen….and 55 years later the Muslim man writes a trailblazing autobiography.

A Jewish grandfather and a Muslim man walk into a New York delicatessen….and 55 years later the Muslim man writes a trailblazing autobiography.

He’s scrawny when he leaves his native home in the Vale of Kashmir, a disputed land in the Himalayan foothills between India and Pakistan. He dodges an impending war. He has no formal passport, just an official residency permit which expired many years ago.

Yet, he takes a chance and, amazingly, boards the last flight from Delhi to Lahore before war breaks out.…it’s an electrifying moment among many, some heartbreaking, some joyful, others human, all too human.

Those moments lead one to believe that the young man was destined for the future of his adopted home, America, where his grit and pluck, his trysts with good luck, his innate belief in common sense all combined to feed his fire within before the fire could feed on him.

Read, how many years ago the Jewish grandfather saw the hunger in the eyes of the Muslim man and sent him on a Mission Impossible to Washington D.C.

Muslim man made the impossible possible, earning the trust of his Jewish mentor who, soon after, handed over the captaincy of his quintessentially Yankee company— Ethan Allen (named after a hero of the American Revolution) — that he had founded during the Great Depression to the young Muslim man named Farooq — which in Islamic tradition means “The Redeemer” or “the one who distinguishes between right and wrong.”

Read how Farooq brought his only previous role as captain (of his college cricket team in his native Kashmir) to bear upon his new captaincy of Ethan Allen in Danbury, Connecticut, its headquarters. Read more »

Ultimately, motivation is irrelevant—who cares if companies are merely pursuing the vegan pound, or if some self-declared “vegans” are self-obsessed wellness slaves ditching dairy for vanity’s sake? If they’re part of a movement that might help slam the brakes on impending environmental doom, then they are surely a force for good.

Ultimately, motivation is irrelevant—who cares if companies are merely pursuing the vegan pound, or if some self-declared “vegans” are self-obsessed wellness slaves ditching dairy for vanity’s sake? If they’re part of a movement that might help slam the brakes on impending environmental doom, then they are surely a force for good. And so, while the requirement for scientific and technical expertise about climate change cannot be denied, there are ways to reconcile this reality with the needs for inclusive, democratic processes about climate action. In his theory of deliberative democracy, the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas (1929-) provides a framework within which democratic processes can distinguish between the different dimensions of discourse – scientific-pragmatic and moral-political. In the context of climate change, this means that there are pathways to address the problem that don’t require scientific or technical expertise, and that are geared towards tackling the collective issues it raises democratically.

And so, while the requirement for scientific and technical expertise about climate change cannot be denied, there are ways to reconcile this reality with the needs for inclusive, democratic processes about climate action. In his theory of deliberative democracy, the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas (1929-) provides a framework within which democratic processes can distinguish between the different dimensions of discourse – scientific-pragmatic and moral-political. In the context of climate change, this means that there are pathways to address the problem that don’t require scientific or technical expertise, and that are geared towards tackling the collective issues it raises democratically. For the past several years, there has been a flood of commentary about how politics is poisoning social life, from first-person stories about “surviving” holidays or breaking off romantic relationships to surveys about the precipitous drop in inter-partisan friendships on college campuses. There are many who think this is a reasonable state of affairs: that “the personal is political” and that it is therefore only natural that all of a person’s social perceptions and choices be suffused with the eerie light of political analysis. But there are also those who dissent. These dissenters say that Americans need to relearn how to disagree with one another productively; the strength of our public dialogue and of our democratic process itself may depend, this crowd says, on our having more and better political discussion and more interactions with those outside our bubbles.

For the past several years, there has been a flood of commentary about how politics is poisoning social life, from first-person stories about “surviving” holidays or breaking off romantic relationships to surveys about the precipitous drop in inter-partisan friendships on college campuses. There are many who think this is a reasonable state of affairs: that “the personal is political” and that it is therefore only natural that all of a person’s social perceptions and choices be suffused with the eerie light of political analysis. But there are also those who dissent. These dissenters say that Americans need to relearn how to disagree with one another productively; the strength of our public dialogue and of our democratic process itself may depend, this crowd says, on our having more and better political discussion and more interactions with those outside our bubbles. It’s an unfashionable thought, but having spent many hours in the university sports hall where constituency votes for Boris Johnson and John McDonnell were counted, I feel freshly in love with democracy. There they all were, local councillors and party workers from across the spectrum; campaigners pursuing personal crusades, from animal rights to the way fathers are treated by the courts; eccentrics dressed as Time Lords. In the hot throng, there were extremists and a few who seemed frankly mad. But most were genial, thoughtful, balanced people giving of their free time to make this a slightly better country. Stuck in Westminster during relentless parliamentary crises, it’s easy to lose sight of just how energising real democracy is. I came home with my cynicism scrubbed off, and exhausted-refreshed.

It’s an unfashionable thought, but having spent many hours in the university sports hall where constituency votes for Boris Johnson and John McDonnell were counted, I feel freshly in love with democracy. There they all were, local councillors and party workers from across the spectrum; campaigners pursuing personal crusades, from animal rights to the way fathers are treated by the courts; eccentrics dressed as Time Lords. In the hot throng, there were extremists and a few who seemed frankly mad. But most were genial, thoughtful, balanced people giving of their free time to make this a slightly better country. Stuck in Westminster during relentless parliamentary crises, it’s easy to lose sight of just how energising real democracy is. I came home with my cynicism scrubbed off, and exhausted-refreshed. At Wat Doi Kham, my local temple in Chiang Mai in Thailand, visitors come in their thousands every week. Bearing money and garlands of jasmine, the devotees prostrate themselves in front of a small Buddha statue, muttering solemn prayers and requesting their wishes be granted. Similar rituals are performed in Buddhist temples across Asia every day and, as at Wat Doi Kham, their focus is usually a mythic representation of the Buddha, sitting serenely in meditation, with a mysterious half-smile, withdrawn and aloof. It is not just Buddhist temples in which the Buddha exists in an entirely mythic form. Buddhist scholars, bewildered by layers of legend as thick as clouds of incense, have mostly given up trying to understand the historical person. This might seem strange, given the ongoing relevance of the Buddha’s ideas and practices, most lately seen in the growing popularity of mindfulness meditation. As Western versions of Buddhism emerge, might space be made for the actual Buddha, a lost sage from ancient India? Might it be possible to separate myth from reality, and so bring the Buddha back into the contemporary conversation?

At Wat Doi Kham, my local temple in Chiang Mai in Thailand, visitors come in their thousands every week. Bearing money and garlands of jasmine, the devotees prostrate themselves in front of a small Buddha statue, muttering solemn prayers and requesting their wishes be granted. Similar rituals are performed in Buddhist temples across Asia every day and, as at Wat Doi Kham, their focus is usually a mythic representation of the Buddha, sitting serenely in meditation, with a mysterious half-smile, withdrawn and aloof. It is not just Buddhist temples in which the Buddha exists in an entirely mythic form. Buddhist scholars, bewildered by layers of legend as thick as clouds of incense, have mostly given up trying to understand the historical person. This might seem strange, given the ongoing relevance of the Buddha’s ideas and practices, most lately seen in the growing popularity of mindfulness meditation. As Western versions of Buddhism emerge, might space be made for the actual Buddha, a lost sage from ancient India? Might it be possible to separate myth from reality, and so bring the Buddha back into the contemporary conversation? Sanjay Reddy in The Print:

Sanjay Reddy in The Print: Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee in The Wire:

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee in The Wire: Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman in Foreign Affairs:

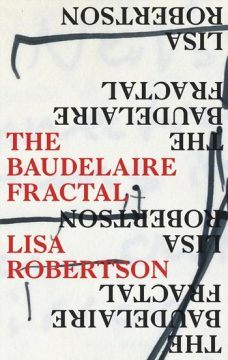

Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman in Foreign Affairs: In the years before a woman becomes a writer, the rooms are never her own, and that can be a very fine thing. Decades before receiving the Baudelairian authorship, when she first moved to Paris as a young woman, Hazel Brown stayed in cheap hotels, admiring the neutrality of spaces designed for everyone and no one: “No judgment, no need, no contract, no seduction: just the free promiscuity of a disrobed mind.” She thereafter sublets teensy, humble apartments, living alongside the unremarkable belongings of people she doesn’t know—an actress (a role-player), a graphologist (a handwriting analyst). She spends her days reading in the park, filling her head with the words of others, of people she also doesn’t know, and picking up boys to kiss and fuck. She is equally enamored of sex and sentences; each, sensual and electrifying, grazes her body, at once possessing it and proving its otherness. She takes menial jobs: one at the summer house of a convalescing widow, for whom she performs all manner of household duties; later, she’s hired to mind the daughter of a wealthy couple, shuttling her from school back to their apartment, where Hazel Brown does the ironing and dusting, playing proxy for the wife and mother who recently returned to work.

In the years before a woman becomes a writer, the rooms are never her own, and that can be a very fine thing. Decades before receiving the Baudelairian authorship, when she first moved to Paris as a young woman, Hazel Brown stayed in cheap hotels, admiring the neutrality of spaces designed for everyone and no one: “No judgment, no need, no contract, no seduction: just the free promiscuity of a disrobed mind.” She thereafter sublets teensy, humble apartments, living alongside the unremarkable belongings of people she doesn’t know—an actress (a role-player), a graphologist (a handwriting analyst). She spends her days reading in the park, filling her head with the words of others, of people she also doesn’t know, and picking up boys to kiss and fuck. She is equally enamored of sex and sentences; each, sensual and electrifying, grazes her body, at once possessing it and proving its otherness. She takes menial jobs: one at the summer house of a convalescing widow, for whom she performs all manner of household duties; later, she’s hired to mind the daughter of a wealthy couple, shuttling her from school back to their apartment, where Hazel Brown does the ironing and dusting, playing proxy for the wife and mother who recently returned to work. Of all the ill-fated revolutions of the

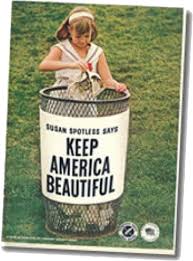

Of all the ill-fated revolutions of the  Modern recycling as we know it—the byzantine system of color-coded bins and asterisk-ridden instruction sheets about what is or isn’t “recyclable”—was conceived in a boardroom. The anti-litter campaigns of the 1950s, championed under the slogan of “Keep America Beautiful,” were funded by the producers of that litter, who sought to position recycling as a viable alternative to the sustainable packaging laws that had percolated in nearly two dozen states. In primetime commercials over the decades, American audiences met characters like Susan Spotless and “The Crying Indian” (played by Italian-American actor Espera Oscar de Corti) who urged consumers to lead the charge against debris: “People start pollution. People can stop it.”

Modern recycling as we know it—the byzantine system of color-coded bins and asterisk-ridden instruction sheets about what is or isn’t “recyclable”—was conceived in a boardroom. The anti-litter campaigns of the 1950s, championed under the slogan of “Keep America Beautiful,” were funded by the producers of that litter, who sought to position recycling as a viable alternative to the sustainable packaging laws that had percolated in nearly two dozen states. In primetime commercials over the decades, American audiences met characters like Susan Spotless and “The Crying Indian” (played by Italian-American actor Espera Oscar de Corti) who urged consumers to lead the charge against debris: “People start pollution. People can stop it.” SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY,

SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY,