Tania Lombrozo in Nautilus:

Last November Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced the birth of twin babies whose germline he claimed to have altered to reduce their susceptibility to contracting HIV. The news of embryo editing and gene-edited babies prompted immediate condemnation both within and beyond the scientific community. An ABC News headline asked: “Genetically edited babies—scientific advancement or playing God?”

Last November Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced the birth of twin babies whose germline he claimed to have altered to reduce their susceptibility to contracting HIV. The news of embryo editing and gene-edited babies prompted immediate condemnation both within and beyond the scientific community. An ABC News headline asked: “Genetically edited babies—scientific advancement or playing God?”

The answer may be “both.” He’s application of gene-editing technology to human embryos flouted norms of scientific transparency and oversight, but even less controversial scientific developments sometimes provoke the reaction that humans are overstepping their appropriate sphere of influence. The arrival of the first IVF baby in 1978, for example, was denounced as playing God with human reproduction1; more than 8 million “IVF-babies” have been born since.2 As we face a global climate crisis, an article at Religion News Service questions whether proposed climate fixes based on geoengineering are playing God with the climate system.3 For many, the idea that mere humans can or should interfere in lofty natural or human domains, whether it’s the earth’s climate or human reproduction, is morally repugnant.

Where does this aversion to playing God come from? And might it present an obstacle to scientific and technological advance?

More here.

It’s the stuff of a Hollywood blockbuster: Five hundred years ago, a son of Christopher Columbus assembled one of the greatest libraries the world has ever known. The volumes inside were mostly lost to history. Now, a precious book summarizing the contents of the library has turned up in a manuscript collection in Denmark.

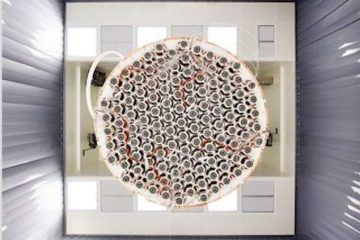

It’s the stuff of a Hollywood blockbuster: Five hundred years ago, a son of Christopher Columbus assembled one of the greatest libraries the world has ever known. The volumes inside were mostly lost to history. Now, a precious book summarizing the contents of the library has turned up in a manuscript collection in Denmark. How do you observe a process that takes more than one trillion times longer than the age of the universe? The XENON Collaboration research team did it with an instrument built to find the most elusive particle in the universe—dark matter. In a paper to be published tomorrow in the journal Nature, researchers announce that they have observed the radioactive decay of xenon-124, which has a half-life of 1.8 X 1022 years.

How do you observe a process that takes more than one trillion times longer than the age of the universe? The XENON Collaboration research team did it with an instrument built to find the most elusive particle in the universe—dark matter. In a paper to be published tomorrow in the journal Nature, researchers announce that they have observed the radioactive decay of xenon-124, which has a half-life of 1.8 X 1022 years. For more than 30 years, the critic Camille Paglia has taught at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. Now a faction of art-school censors wants her fired for sharing wrong opinions on matters of sex, gender identity, and sexual assault.

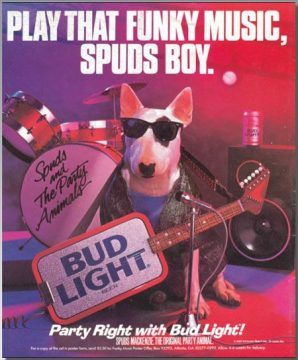

For more than 30 years, the critic Camille Paglia has taught at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. Now a faction of art-school censors wants her fired for sharing wrong opinions on matters of sex, gender identity, and sexual assault. For a concrete demonstration, consider comedian Yakov Smirnoff, careening at Spuds Factor 10. Today, Smirnoff’s cultural activities have largely been quarantined to the town of

For a concrete demonstration, consider comedian Yakov Smirnoff, careening at Spuds Factor 10. Today, Smirnoff’s cultural activities have largely been quarantined to the town of  For some, the Grand Bazaar, with its remnants of Ottoman behaviors and designs and artisanal crafts, might suggest itself as Turkey’s most authentic self, but in Turkey the quest for authenticity often leads you further and further away from how life is actually lived. Since even before the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923, Turks have seen the Grand Bazaar eclipsed many times: first by the European-style shopping boulevard, then by the stand-alone shopping mall, then by the stand-alone luxury shopping mall and apartment and office complex, and then most recently—in one of neoliberalism’s uglier incarnations—by the luxury shopping mall that invades and occupies what was once a fine nineteenth-century building on a beloved European boulevard. (See: the Demirören mall on İstiklal Street, itself a commercial and artistic center during the Ottoman and modern eras.) Turkey’s cities have also expanded tenfold—Istanbul is roughly four times London’s physical size—and bazaars and pedestrianized shopping streets now serve every neighborhood, each of them microcities with their own microeconomies, their own bakkal (corner shop) and manav (greengrocer) and kasap (butcher), which are as faithfully patronized as they would have been a century ago. By now every neighborhood also has its own mall. The Galleria belongs to the neighborhood of Ataköy, Forum Istanbul belongs to Bayrampaşa, Zorlu Center to Gayrettepe, Kanyon to Levent, İstinye Park to İstinye. There is even a Mall of Istanbul—though it should be called the Mall of Başakşehir, where it is actually located. I would never go there, for example, because it is an hour and fifteen minutes away by public transportation. The Mall of Istanbul belongs to another Istanbul entirely.

For some, the Grand Bazaar, with its remnants of Ottoman behaviors and designs and artisanal crafts, might suggest itself as Turkey’s most authentic self, but in Turkey the quest for authenticity often leads you further and further away from how life is actually lived. Since even before the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923, Turks have seen the Grand Bazaar eclipsed many times: first by the European-style shopping boulevard, then by the stand-alone shopping mall, then by the stand-alone luxury shopping mall and apartment and office complex, and then most recently—in one of neoliberalism’s uglier incarnations—by the luxury shopping mall that invades and occupies what was once a fine nineteenth-century building on a beloved European boulevard. (See: the Demirören mall on İstiklal Street, itself a commercial and artistic center during the Ottoman and modern eras.) Turkey’s cities have also expanded tenfold—Istanbul is roughly four times London’s physical size—and bazaars and pedestrianized shopping streets now serve every neighborhood, each of them microcities with their own microeconomies, their own bakkal (corner shop) and manav (greengrocer) and kasap (butcher), which are as faithfully patronized as they would have been a century ago. By now every neighborhood also has its own mall. The Galleria belongs to the neighborhood of Ataköy, Forum Istanbul belongs to Bayrampaşa, Zorlu Center to Gayrettepe, Kanyon to Levent, İstinye Park to İstinye. There is even a Mall of Istanbul—though it should be called the Mall of Başakşehir, where it is actually located. I would never go there, for example, because it is an hour and fifteen minutes away by public transportation. The Mall of Istanbul belongs to another Istanbul entirely. Not all readers will agree with the claims Miller makes for L.E.L.’s significance, but it is hard to dispute that the very ephemerality of L.E.L.’s work makes her a peculiarly appropriate spokeswoman for a literary age marked by artifice. L.E.L. came to maturity just as the voices of Shelley, Keats and Byron faded away and her life was over by the time the dominant figures of the Victorian novel made their names. Her nearest literary contemporaries were Edward Bulwer, Lady Blessington and the young Disraeli, all of whose early work shared in the neglect accorded to hers. From the late 1820s, the whiff of scandal attached to L.E.L. barred her from more respectable drawing rooms; the majority of her acquaintances were drawn from the raffish circles surrounding the Bulwers and a small circle of equally shady figures. Mary Anne Wyndham Lewis, who subsequently married Disraeli and courted scandal herself, gave her dresses and jewellery, and the art critic Samuel Carter Hall abetted her relationship with Jerdan. Jerdan himself never acknowledged the central role L.E.L. played in his emotional life, and, throughout the period in which she conceived and bore his children, he remained with his wife and legitimate children, escorting his mistress to parties before returning to the family home while she sought sanctuary in attic lodgings nearby.

Not all readers will agree with the claims Miller makes for L.E.L.’s significance, but it is hard to dispute that the very ephemerality of L.E.L.’s work makes her a peculiarly appropriate spokeswoman for a literary age marked by artifice. L.E.L. came to maturity just as the voices of Shelley, Keats and Byron faded away and her life was over by the time the dominant figures of the Victorian novel made their names. Her nearest literary contemporaries were Edward Bulwer, Lady Blessington and the young Disraeli, all of whose early work shared in the neglect accorded to hers. From the late 1820s, the whiff of scandal attached to L.E.L. barred her from more respectable drawing rooms; the majority of her acquaintances were drawn from the raffish circles surrounding the Bulwers and a small circle of equally shady figures. Mary Anne Wyndham Lewis, who subsequently married Disraeli and courted scandal herself, gave her dresses and jewellery, and the art critic Samuel Carter Hall abetted her relationship with Jerdan. Jerdan himself never acknowledged the central role L.E.L. played in his emotional life, and, throughout the period in which she conceived and bore his children, he remained with his wife and legitimate children, escorting his mistress to parties before returning to the family home while she sought sanctuary in attic lodgings nearby. Not far from the monstrous checkpoint at Qalandia – the main gateway through which the Israeli military controls the passage of human beings between Ramallah and Jerusalem – is a small, outdoor, stonecutters’ workshop, one of hundreds scattered throughout the West Bank. Whatever may be happening at the checkpoint, at least one worker can usually be seen standing in the stone-cutters’ yard, his face, hair and clothes caked with the same white dust that covers the high concrete wall and the watchtower, where it mixes with the black smoke and char from burning tyres and the molotov cocktails that local youths, on particularly bad days, hurl at the checkpoint and barrier that confine them.

Not far from the monstrous checkpoint at Qalandia – the main gateway through which the Israeli military controls the passage of human beings between Ramallah and Jerusalem – is a small, outdoor, stonecutters’ workshop, one of hundreds scattered throughout the West Bank. Whatever may be happening at the checkpoint, at least one worker can usually be seen standing in the stone-cutters’ yard, his face, hair and clothes caked with the same white dust that covers the high concrete wall and the watchtower, where it mixes with the black smoke and char from burning tyres and the molotov cocktails that local youths, on particularly bad days, hurl at the checkpoint and barrier that confine them. Conceived by

Conceived by  Abdullah the Cossack”, the antihero of HM Naqvi’s follow-up to the award-winning

Abdullah the Cossack”, the antihero of HM Naqvi’s follow-up to the award-winning  L

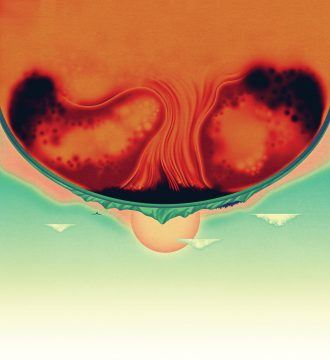

L Wallace-Wells stresses that these scenarios are the signs not of a new normal, but of a world in which “normal” ceases to be a useful framework for understanding an environment that is constantly changing, and almost always for the worse. “By 2040, the summer of 2018 will likely seem normal,” he writes. “But extreme weather is not a matter of ‘normal’; it is what roars back at us from the ever-worsening fringe of climate events. This is among the scariest features of rapid climate change: not that it changes the everyday experience of the world, though it does that, and dramatically; but that it makes once-unthinkable outlier events much more common, and ushers whole new categories of disaster into the realm of the possible.”

Wallace-Wells stresses that these scenarios are the signs not of a new normal, but of a world in which “normal” ceases to be a useful framework for understanding an environment that is constantly changing, and almost always for the worse. “By 2040, the summer of 2018 will likely seem normal,” he writes. “But extreme weather is not a matter of ‘normal’; it is what roars back at us from the ever-worsening fringe of climate events. This is among the scariest features of rapid climate change: not that it changes the everyday experience of the world, though it does that, and dramatically; but that it makes once-unthinkable outlier events much more common, and ushers whole new categories of disaster into the realm of the possible.” To read

To read It is one of the great dilemmas of climate change: We take such comfort from air conditioning that worldwide energy consumption for that purpose has already tripled since 1990. It is on track to grow even faster through mid-century—and assuming fossil-fuel–fired power plants provide the electricity, that could cause enough carbon dioxide emissions to warm the planet by another deadly half-degree Celsius. A

It is one of the great dilemmas of climate change: We take such comfort from air conditioning that worldwide energy consumption for that purpose has already tripled since 1990. It is on track to grow even faster through mid-century—and assuming fossil-fuel–fired power plants provide the electricity, that could cause enough carbon dioxide emissions to warm the planet by another deadly half-degree Celsius. A  The idea that humans have cognitive instincts is a cornerstone of evolutionary psychology, pioneered by Leda Cosmides, John Tooby and Steven Pinker in the 1990s. ‘[O]ur modern skulls house a Stone Age mind,’

The idea that humans have cognitive instincts is a cornerstone of evolutionary psychology, pioneered by Leda Cosmides, John Tooby and Steven Pinker in the 1990s. ‘[O]ur modern skulls house a Stone Age mind,’  Climate change is the greatest challenge humanity has collectively faced. That challenge is, to put it mildly, practical; but it also poses a problem to the imagination. Our politics, our societies, are arranged around individual and group interests. These interests have to do with class, or ethnicity, or gender, or economics — make your own list. By asserting these interests, we call out to each other so that as a collective we see and hear one another. From that beginning, we construct the three overlapping, interacting R’s of recognition, representation and rights.

Climate change is the greatest challenge humanity has collectively faced. That challenge is, to put it mildly, practical; but it also poses a problem to the imagination. Our politics, our societies, are arranged around individual and group interests. These interests have to do with class, or ethnicity, or gender, or economics — make your own list. By asserting these interests, we call out to each other so that as a collective we see and hear one another. From that beginning, we construct the three overlapping, interacting R’s of recognition, representation and rights.