Jim Robbins in The New York Times:

ELY, Nev. — A crew of five wildlife biologists wearing overalls, helmets and headlamps walked up the flanks of a juniper-studded mountain and climbed through stout steel bars to enter an abandoned mine that serves as a bat hibernaculum.

ELY, Nev. — A crew of five wildlife biologists wearing overalls, helmets and headlamps walked up the flanks of a juniper-studded mountain and climbed through stout steel bars to enter an abandoned mine that serves as a bat hibernaculum.

The swinging white light of the headlamps probed cracks and crevices in the walls of the long dark and narrow tunnel, as the team walked half a mile into the earth. When they spied a bat, they gently plucked the mouse-sized, chestnut brown mammal — Townsend’s long eared and Western small footed are the two most abundant species here — off the walls and deposited them in white cloth bags. A lone big brown bat was also gathered. At one point a bat, disturbed by the scientific ruckus, fluttered by, the headlamps illuminating its membranous, négligée-thin wings. During the survey in November, the bats were in their pre-hibernation phase, clinging to the gray rock wall with tiny grappling hook-like feet, gently breathing. They are in full hibernation mode now. “They are biologically interesting,” said Catherine G. Haase, a postdoctoral researcher from Montana State University, as she affectionately handled a docile bat. “And they are really cute.”

Cute, interesting and facing a deeply uncertain future. This foray is part of a continentwide effort, from Canada to Oklahoma, to plumb mines and caves in hopes of figuring out how a virulent and rapidly spreading invasive fungal bat disease called white-nose syndrome, which is bearing down on the West, will behave when it hits the native populations here. “White-nose syndrome represents one of the most consequential wildlife diseases of modern times,” wrote the authors of one recent paper published in mSphere, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology. Since 2006, “the disease has killed millions of bats and threatens several formerly abundant species with extirpation or extinction.” White-nose syndrome, caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd), is named for the fuzzy spots that appear on bats’ noses and wings.

More here.

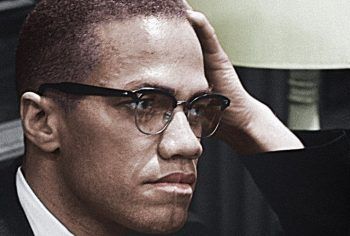

More than fifty years after his death, Malcolm X remains a polarizing and misunderstood figure. Not unlike the leader he is too often contrasted with—Martin Luther King, Jr.—he has been a symbol to mobilize around, a foil to abjure, or a commodity to sell, rather than a thinker to engage. As political philosopher Brandon Terry reminded us

More than fifty years after his death, Malcolm X remains a polarizing and misunderstood figure. Not unlike the leader he is too often contrasted with—Martin Luther King, Jr.—he has been a symbol to mobilize around, a foil to abjure, or a commodity to sell, rather than a thinker to engage. As political philosopher Brandon Terry reminded us  Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

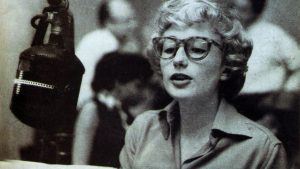

Blossom Dearie: incredibly, it was her legal name. The pianist and jazz singer was born Margrethe Blossom Dearie in 1924; all she had to do to get her stage name was to drop the Margrethe. The name perhaps overdetermines the voice. But you’ve got to hear the voice. Light and slim, with little to no vibrato, Dearie’s voice is ingenuous to such a degree that you begin to wonder whether it isn’t, in fact, the least ingenuous thing you have ever heard. It echoes with the four-square court—or was that the tomb? Imagine a sphinx posing her fatal riddle to Oedipus. Then ditch the immortal growl and try hearing, instead, a girl. That’s Dearie, singing her riddles of love and disaster. But unlike the sphinx, she wagers her own life, not other people’s. She knows the stakes, and still, that light, slim voice, with no vibrato, comes floating onto the air.

Blossom Dearie: incredibly, it was her legal name. The pianist and jazz singer was born Margrethe Blossom Dearie in 1924; all she had to do to get her stage name was to drop the Margrethe. The name perhaps overdetermines the voice. But you’ve got to hear the voice. Light and slim, with little to no vibrato, Dearie’s voice is ingenuous to such a degree that you begin to wonder whether it isn’t, in fact, the least ingenuous thing you have ever heard. It echoes with the four-square court—or was that the tomb? Imagine a sphinx posing her fatal riddle to Oedipus. Then ditch the immortal growl and try hearing, instead, a girl. That’s Dearie, singing her riddles of love and disaster. But unlike the sphinx, she wagers her own life, not other people’s. She knows the stakes, and still, that light, slim voice, with no vibrato, comes floating onto the air.

I don’t know how much you know about Petrarch. My guess is that you know him as a poet, primarily for his sonnets. Maybe you associate him with early Italian humanism and its reinvigorated dedication to the wisdom of classical Antiquity. Or perhaps you think of him as someone who expressed transcendental truths about the soul and its searching and wandering nature.

I don’t know how much you know about Petrarch. My guess is that you know him as a poet, primarily for his sonnets. Maybe you associate him with early Italian humanism and its reinvigorated dedication to the wisdom of classical Antiquity. Or perhaps you think of him as someone who expressed transcendental truths about the soul and its searching and wandering nature. History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events.

History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events. A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann)

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann) impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt?

impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt?

Michael E Mann is one of two climate scientists who have been awarded the 2019

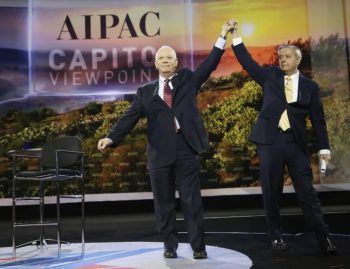

Michael E Mann is one of two climate scientists who have been awarded the 2019  One thing that should be said about Representative Ilhan Omar’s tweet about the power of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (more commonly known as AIPAC, or the “Israel lobby”) is that the hysterical reaction to it proved her main point: The power of AIPAC over members of Congress is literally awesome, although not in a good way. Has anyone ever seen so many members of Congress, of both parties, running to the microphones and sending out press releases to denounce one first-termer for criticizing the power of… a lobby?

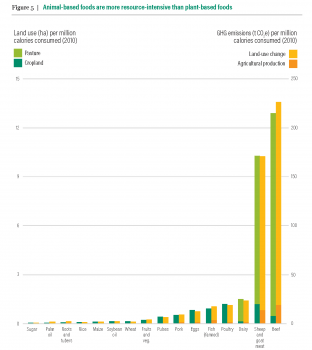

One thing that should be said about Representative Ilhan Omar’s tweet about the power of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (more commonly known as AIPAC, or the “Israel lobby”) is that the hysterical reaction to it proved her main point: The power of AIPAC over members of Congress is literally awesome, although not in a good way. Has anyone ever seen so many members of Congress, of both parties, running to the microphones and sending out press releases to denounce one first-termer for criticizing the power of… a lobby? For decades, environmentalists have been rightly concerned about the environmental impact of humanity’s food systems. Often, this has meant advocating for shifting diets — in particular, away from meat, given its outsized environmental impact.

For decades, environmentalists have been rightly concerned about the environmental impact of humanity’s food systems. Often, this has meant advocating for shifting diets — in particular, away from meat, given its outsized environmental impact. SATIRES OF THE ART WORLD

SATIRES OF THE ART WORLD