Month: February 2019

Rushdie’s Deal with the Devil

Kevin Blankinship in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

ON VALENTINE’S DAY 1989, the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, declared a death sentence on British Indian novelist Salman Rushdie for his book The Satanic Verses, along with any who helped its release: “I ask all Muslims to execute them wherever they find them.” The Ayatollah accused Rushdie of blasphemy, of sullying Islam and its prophet Muhammad, though many saw it as a desperate cry for popular support after a humiliating decade of war with Iraq. There followed riots, demonstrations, and book burnings across Europe and the Middle East. Death threats poured in. Viking Penguin, Rushdie’s UK publisher, was threatened with bombings. The author himself was forced into hiding under the pseudonym “Joseph Anton,” a mash-up of Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov and the title of Rushdie’s 2012 memoir of the controversy. The media and public still remember it as “The Rushdie Affair,” though most people born after the 1980s have never heard of it.

ON VALENTINE’S DAY 1989, the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, declared a death sentence on British Indian novelist Salman Rushdie for his book The Satanic Verses, along with any who helped its release: “I ask all Muslims to execute them wherever they find them.” The Ayatollah accused Rushdie of blasphemy, of sullying Islam and its prophet Muhammad, though many saw it as a desperate cry for popular support after a humiliating decade of war with Iraq. There followed riots, demonstrations, and book burnings across Europe and the Middle East. Death threats poured in. Viking Penguin, Rushdie’s UK publisher, was threatened with bombings. The author himself was forced into hiding under the pseudonym “Joseph Anton,” a mash-up of Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov and the title of Rushdie’s 2012 memoir of the controversy. The media and public still remember it as “The Rushdie Affair,” though most people born after the 1980s have never heard of it.

Unlike the recent attack on lampoon magazine Charlie Hebdo or the threats against Danish daily Jyllands-Posten, the creative text behind the Rushdie Affair was renowned as high art. It netted the 1988 Whitbread Award and was named a Booker Prize finalist (Rushdie had already won a Booker for his second novel, Midnight’s Children). It was lauded by the Who’s Who of 20th-century literature: Norman Mailer, Bruce Chatwin, Marina Warner, Joan Didion, Martin Amis, Nadine Gordimer, Peter Carey, David Lodge.

More here.

What Is Trump?

Dylan Riley in New Left Review:

Debates around the politics of Trump and other new-right leaders have led to an explosion of historical analogizing, with the experience of the 1930s looming large. According to much of this commentary, Trump—not to mention Orbán, Kaczynski, Modi, Duterte, Erdoğan—is an authoritarian figure justifiably compared to those of the fascist era. The proponents of this view span the political spectrum, from neoconservative right and liberal mainstream to anarchist insurrectionary. The typical rhetorical device they deploy is to advance and protect the identification of Trump with fascism by way of nominal disclaimers of it. Thus for Timothy Snyder, a Cold War liberal, ‘There are differences’—yet: ‘Trump has made his debt to fascism clear from the beginning. From his initial linkage of immigrants to sexual violence to his continued identification of journalists as “enemies” . . . he has given us every clue we need.’ For Snyder’s Yale colleague, Jason Stanley, ‘I’m not arguing that Trump is a fascist leader, in the sense that he’s ruling as a fascist’—but: ‘as far as his rhetorical strategy goes, it’s very fascist.’ For their fellow liberal Richard Evans, at Cambridge: ‘It’s not the same’—however: ‘Trump is a 21st-century would-be dictator who uses the unprecedented power of social media and the Internet to spread conspiracy theories’—‘worryingly reminiscent of the fascists of the 1920s and 1930s.’

Debates around the politics of Trump and other new-right leaders have led to an explosion of historical analogizing, with the experience of the 1930s looming large. According to much of this commentary, Trump—not to mention Orbán, Kaczynski, Modi, Duterte, Erdoğan—is an authoritarian figure justifiably compared to those of the fascist era. The proponents of this view span the political spectrum, from neoconservative right and liberal mainstream to anarchist insurrectionary. The typical rhetorical device they deploy is to advance and protect the identification of Trump with fascism by way of nominal disclaimers of it. Thus for Timothy Snyder, a Cold War liberal, ‘There are differences’—yet: ‘Trump has made his debt to fascism clear from the beginning. From his initial linkage of immigrants to sexual violence to his continued identification of journalists as “enemies” . . . he has given us every clue we need.’ For Snyder’s Yale colleague, Jason Stanley, ‘I’m not arguing that Trump is a fascist leader, in the sense that he’s ruling as a fascist’—but: ‘as far as his rhetorical strategy goes, it’s very fascist.’ For their fellow liberal Richard Evans, at Cambridge: ‘It’s not the same’—however: ‘Trump is a 21st-century would-be dictator who uses the unprecedented power of social media and the Internet to spread conspiracy theories’—‘worryingly reminiscent of the fascists of the 1920s and 1930s.’

More here.

Why Elizabeth Warren’s Wealth Tax Would Work

John Cassidy in The New Yorker:

In 1995, Edward Wolff, an economist at N.Y.U., published a short book called “Top Heavy,” which detailed the increasingly alarming concentration of wealth in the United States, and warned of the threat that it posed to American democracy, as the ultra-rich sought to exercise more political power. At the time, the richest one per cent of families controlled about forty per cent of all household wealth—defined as stocks, bonds, other financial assets, equity in private businesses, trusts, real estate, and bank deposits—while much of the population had virtually no wealth at all once debts and mortgages were taken into account. To address this disparity, Wolff called for the introduction of an annual tax on wealth. Aware that this might be considered a radical idea, he kept his proposed tax rates at pretty low levels. Under his plan, households with a net worth of a hundred thousand dollars would pay five cents in tax on every hundred dollars of their wealth; the rate would rise to thirty cents per hundred dollars for households worth a million dollars or more. (Back then, about three per cent of U.S. households fell into the latter bracket.)

In 1995, Edward Wolff, an economist at N.Y.U., published a short book called “Top Heavy,” which detailed the increasingly alarming concentration of wealth in the United States, and warned of the threat that it posed to American democracy, as the ultra-rich sought to exercise more political power. At the time, the richest one per cent of families controlled about forty per cent of all household wealth—defined as stocks, bonds, other financial assets, equity in private businesses, trusts, real estate, and bank deposits—while much of the population had virtually no wealth at all once debts and mortgages were taken into account. To address this disparity, Wolff called for the introduction of an annual tax on wealth. Aware that this might be considered a radical idea, he kept his proposed tax rates at pretty low levels. Under his plan, households with a net worth of a hundred thousand dollars would pay five cents in tax on every hundred dollars of their wealth; the rate would rise to thirty cents per hundred dollars for households worth a million dollars or more. (Back then, about three per cent of U.S. households fell into the latter bracket.)

Despite the modest scale of Wolff’s proposal, it didn’t get much traction in the policy world. Prior to publishing the book, he did have a lunch meeting with Bill Bradley, the Democratic senator from New Jersey, where they discussed the idea, but that was as far as it went. “He sounded enthusiastic at the lunch, but when push came to shove he walked away,” Wolff recalled when I spoke with him earlier this week. “He thought that politically it was dynamite.”

Twenty-five years later, how have things changed?

More here.

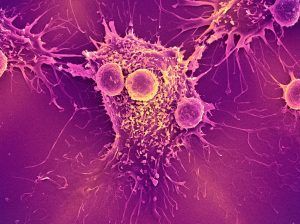

The ‘Complete’ Cancer Cure Story Is Both Bogus And Tragic

Unfortunately, I am one of the people who should have known better but relying on the Jerusalem Post normally being a reasonable paper I posted what has turned out to be a very shady story here on 3QD. I am sorry.

Megan Molteni in Wired:

On Monday, the Jerusalem Post, a centrist Israeli newspaper, published an online story profiling a small company called Accelerated Evolution Biotechnologies that has been working on a potential anti-cancer drug cocktail since 2000. It was somewhat cautiously headlined “A Cure for Cancer? Israeli Scientists Think They Found One” and relied almost entirely on an interview with the company’s board chair, Dan Aridor, one of just three individuals listed on AEBi’s website. In it, Aridor made a series of sweeping claims, including this eye-popper: “We believe we will offer in a year’s time a complete cure for cancer.

On Monday, the Jerusalem Post, a centrist Israeli newspaper, published an online story profiling a small company called Accelerated Evolution Biotechnologies that has been working on a potential anti-cancer drug cocktail since 2000. It was somewhat cautiously headlined “A Cure for Cancer? Israeli Scientists Think They Found One” and relied almost entirely on an interview with the company’s board chair, Dan Aridor, one of just three individuals listed on AEBi’s website. In it, Aridor made a series of sweeping claims, including this eye-popper: “We believe we will offer in a year’s time a complete cure for cancer.

It was an especially brash move considering the company has not conducted a single trial in humans or published an ounce of data from its completed studies of petri dish cells and rodents in cages. Under normal drug development proceedings, a pharmaceutical startup would submit such preclinical work to peer review to support any claims and use it to drum up funding for clinical testing.

More here.

Friday Poem

Heritage Test

I might spit in a bag and wait to find out

I don’t have enough African in me to be

excellent. Afua says

one drop and you’re black but I still remember

Ebony, who is herself mixed, tagging me

on Facebook, “LOL @RaymondAntrobus

IS NOT BLACK!” just as I was visiting

Bob Marley’s grave and he came back

from the dead as a duppy and laughed

at my hair as he sang Slave Driver

and threw his shoe polished dreadlocks

across the cemetery.

My middle name is Sulaiman.

An African name. It’s always made people

look at me sideways, even other

mixed race people look at me like the ghosts

of Picasso’s African masks.

I was drawing myself as a blue hedgehog

before I was drawing myself

as Alex The Kid, before

I started making friends with other

mixed race boys in London with African names.

Je-Je, Eli, Dawit, all of us, secretly needing

each other’s praise. Sometimes

I just want to sit on Dad’s lap again, watching

Titanic while he yells

“white people are crazy!”

and tickles under my armpits

while I squirm, laughing

as the picture of Marcus Garvey

stares from the wall––

that’s why I laugh now

when Drake spits “Black excellence!

but I guess when it comes to me

it’s not the same,” the line pulling me

out of my body, pinning me

to the wall. What happens if I spit

in a bag and find out I don’t have enough

African in me to be my own portrait?