Emily Lordi in The New Yorker:

“I don’t want to make somebody else,” Toni Morrison’s character Sula declares, when urged to get married and have kids, “I want to make myself.” Morrison herself might have understood this to be a false dichotomy—she was a single mother of two by the time she published “Sula,” her second novel, in 1973—but, in her fiction, she split the individualist impulse to make an artful life and the domestic drive to make a home between two characters: Sula and her best friend, Nel. The tensions between these two desires animate the body of fiction and nonfiction about the private lives of women and mothers. It’s a canon that has been dominated by the accounts of white, straight writers, but it now includes Michelle Obama’s blockbuster memoir, “Becoming.”

“I don’t want to make somebody else,” Toni Morrison’s character Sula declares, when urged to get married and have kids, “I want to make myself.” Morrison herself might have understood this to be a false dichotomy—she was a single mother of two by the time she published “Sula,” her second novel, in 1973—but, in her fiction, she split the individualist impulse to make an artful life and the domestic drive to make a home between two characters: Sula and her best friend, Nel. The tensions between these two desires animate the body of fiction and nonfiction about the private lives of women and mothers. It’s a canon that has been dominated by the accounts of white, straight writers, but it now includes Michelle Obama’s blockbuster memoir, “Becoming.”

What Obama brings to this genre is, first, a powerful sense of self, which precedes and exceeds her domestic relationships—the book’s three sections are titled “Becoming Me,” “Becoming Us,” “Becoming More”—and, second, a conviction that the roles of wife and mother are themselves undefined. She makes and remakes her relationship to both throughout her adult life. In this, she draws on the literature of black women’s self-making that “Sula” represents. The modern matron saint of that tradition is Zora Neale Hurston, who, in a 1928 essay, describes “How It Feels to Be Colored Me”: a prismatic, mutable experience of being a loner, a spectacle, an ordinary woman, a goddess (“the eternal feminine with its string of beads”). Lucille Clifton shares Hurston’s sense of the need to invent oneself in a world without reliable mirrors or maps; as she writes in a poem, from 1992, “i had no model. / born in babylon / both nonwhite and woman / what did I see to be except myself? / i made it up…” Like these writers, Obama exposes the particular pressures and thrills of black women’s self-creation. But she also details the rather more modest creation of a stable domestic life. By bringing motherhood, marriage, and self-making together in “Becoming,” she combines the possibilities that Sula and Nel represent.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, we will publish at least one post dedicated to Black History Month)

During a six-month period in 1889, nearly 900,000 people descended upon the sprawling Universal Exposition in Paris, the fourth world’s fair to be held in the city, this one constructed in the shadows of the new Eiffel Tower. For the average Parisian strolling down the Esplanade des Invalides, the sight of a Tunisian palace, an Algerian bazaar, or a Cambodian pagoda would have meant pure enchantment, and nobody was more enchanted than Claude Debussy. Inside a replica of a Javanese village, the 26-year-old composer encountered the ensemble of bronze metallophones, gongs, and other instruments known as a gamelan, the musicians in the pavilion joined by a male singer and four young female dancers. For an artist recoiling from the rigid orthodoxy of the conservatory, the music’s bright, sensuous timbres, its feeling of spaciousness, and its vaguely pentatonic scales offered Debussy a path toward something new, even if he struggled to make sense of what he heard in the context of western harmony and counterpoint.

During a six-month period in 1889, nearly 900,000 people descended upon the sprawling Universal Exposition in Paris, the fourth world’s fair to be held in the city, this one constructed in the shadows of the new Eiffel Tower. For the average Parisian strolling down the Esplanade des Invalides, the sight of a Tunisian palace, an Algerian bazaar, or a Cambodian pagoda would have meant pure enchantment, and nobody was more enchanted than Claude Debussy. Inside a replica of a Javanese village, the 26-year-old composer encountered the ensemble of bronze metallophones, gongs, and other instruments known as a gamelan, the musicians in the pavilion joined by a male singer and four young female dancers. For an artist recoiling from the rigid orthodoxy of the conservatory, the music’s bright, sensuous timbres, its feeling of spaciousness, and its vaguely pentatonic scales offered Debussy a path toward something new, even if he struggled to make sense of what he heard in the context of western harmony and counterpoint.

From where I work at the University of Sydney, you cannot see the ocean. However, in Australia, the ocean is part of our national consciousness. This is perhaps why I think of the research literature as an ocean, linking researchers in disparate yet ultimately connected fields. Just as there is growing alarm about our rising, polluted oceans, scientists are increasingly talking about the swelling research literature and its contamination by incorrect research results.

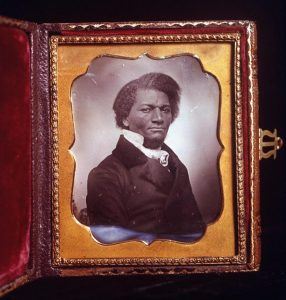

From where I work at the University of Sydney, you cannot see the ocean. However, in Australia, the ocean is part of our national consciousness. This is perhaps why I think of the research literature as an ocean, linking researchers in disparate yet ultimately connected fields. Just as there is growing alarm about our rising, polluted oceans, scientists are increasingly talking about the swelling research literature and its contamination by incorrect research results. Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass On Monday, a trail runner in Colorado was attacked by a mountain lion. While fighting to defend his life, the man managed to kill the lion. This is how he did that.

On Monday, a trail runner in Colorado was attacked by a mountain lion. While fighting to defend his life, the man managed to kill the lion. This is how he did that. Researchers in

Researchers in

As Zachary Lazar put it in his New York Times review: “It helps that James . . . is a virtuoso at depicting violence, particularly at the beginning of this book, where we witness scene after scene of astonishing sadism, as young men and boys are impelled by savagery toward savagery of their own.” Later he writes, “The novel’s great strength is the way it conveys the degradation of Kingston’s slums.” Lazar’s praise, the elements of the novel he highlighted, would be echoed again and again in each review I read, and I can’t say he’s wrong. James ismasterful with violence and sadism, and Kingston’s slums are vividly portrayed.

As Zachary Lazar put it in his New York Times review: “It helps that James . . . is a virtuoso at depicting violence, particularly at the beginning of this book, where we witness scene after scene of astonishing sadism, as young men and boys are impelled by savagery toward savagery of their own.” Later he writes, “The novel’s great strength is the way it conveys the degradation of Kingston’s slums.” Lazar’s praise, the elements of the novel he highlighted, would be echoed again and again in each review I read, and I can’t say he’s wrong. James ismasterful with violence and sadism, and Kingston’s slums are vividly portrayed. If, as one sometimes hears, people can be divided into two groups—those who run away from violence and danger and those who run toward it—something similar could be said about ones who, like Brassaï and Caravaggio, see themselves as nocturnal beings, as opposed to those who see themselves as creatures of daylight, or even identify with that loaded appellation morning person. Some, like Sancho Panza, wish only to go to bed at twilight and to sleep undisturbed—escaping the real and imagined terrors that they perhaps sense lurk in the dark. Others, like Don Quixote, feel the compulsion to stay awake for at least part of the night, to maintain a vigil.

If, as one sometimes hears, people can be divided into two groups—those who run away from violence and danger and those who run toward it—something similar could be said about ones who, like Brassaï and Caravaggio, see themselves as nocturnal beings, as opposed to those who see themselves as creatures of daylight, or even identify with that loaded appellation morning person. Some, like Sancho Panza, wish only to go to bed at twilight and to sleep undisturbed—escaping the real and imagined terrors that they perhaps sense lurk in the dark. Others, like Don Quixote, feel the compulsion to stay awake for at least part of the night, to maintain a vigil. You don’t turn to Thorn’s memoirs (this is her second; she is also a New Statesman columnist) for rock ’n’ roll name-dropping, but for someone who can – to quote her quoting Updike – “give the mundane its beautiful due”. My brother-in-law says of being a fan of the band: “The only difference between them and us was that we were listening to Everything but the Girl, while they were in Everything but the Girl.” The past is another planet and the diary twinkles with the arcane poetry of lost brand names – Aqua Manda, Green Shield Stamps.

You don’t turn to Thorn’s memoirs (this is her second; she is also a New Statesman columnist) for rock ’n’ roll name-dropping, but for someone who can – to quote her quoting Updike – “give the mundane its beautiful due”. My brother-in-law says of being a fan of the band: “The only difference between them and us was that we were listening to Everything but the Girl, while they were in Everything but the Girl.” The past is another planet and the diary twinkles with the arcane poetry of lost brand names – Aqua Manda, Green Shield Stamps. Last fall it was voted America’s best-loved book. This winter it made it to Broadway, grossing more at the box office in its first full week than any other play in history. Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” became a classic the moment it was published in 1960 – a tale of racial injustice set in Depression-era Alabama told through the eyes of 6-year-old Scout. It garnered the Pulitzer Prize in 1961, and its movie adaptation won three Oscars in 1963. That it has smashed theater records and risen to the top of

Last fall it was voted America’s best-loved book. This winter it made it to Broadway, grossing more at the box office in its first full week than any other play in history. Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” became a classic the moment it was published in 1960 – a tale of racial injustice set in Depression-era Alabama told through the eyes of 6-year-old Scout. It garnered the Pulitzer Prize in 1961, and its movie adaptation won three Oscars in 1963. That it has smashed theater records and risen to the top of  “I don’t want to make somebody else,” Toni Morrison’s character Sula declares, when urged to get married and have kids, “I want to make myself.” Morrison herself might have understood this to be a false dichotomy—she was a single mother of two by the time she published “

“I don’t want to make somebody else,” Toni Morrison’s character Sula declares, when urged to get married and have kids, “I want to make myself.” Morrison herself might have understood this to be a false dichotomy—she was a single mother of two by the time she published “ In Diego Rivera’s La creación, Nahui Olin sits among a gathering of figures that represent “the fable,” draped in gold and blue. She appears as the figure of Erotic Poetry, fitting for what she was known for at the time: her erotic writing and sexual freedom.

In Diego Rivera’s La creación, Nahui Olin sits among a gathering of figures that represent “the fable,” draped in gold and blue. She appears as the figure of Erotic Poetry, fitting for what she was known for at the time: her erotic writing and sexual freedom. A young evolutionary biologist, Barrett had come to Nebraska’s Sand Hills with a grand plan. He would build large outdoor enclosures in areas with light or dark soil, and fill them with captured mice. Over time, he would see how these rodents adapted to the different landscapes—a deliberate, real-world test of natural selection, on a scale that biologists rarely attempt.

A young evolutionary biologist, Barrett had come to Nebraska’s Sand Hills with a grand plan. He would build large outdoor enclosures in areas with light or dark soil, and fill them with captured mice. Over time, he would see how these rodents adapted to the different landscapes—a deliberate, real-world test of natural selection, on a scale that biologists rarely attempt. When

When  And yet the most surprising aspect of the tiny-house phenomenon might be that, while the lifestyle has never been more visible, real-life tiny-house dwellers are hard to find. Fewer than ten thousand of the homes are estimated to exist nationwide. The impracticalities of tiny living—shoebox-sized sinks, closetless rooms—can be daunting, but it’s not only that. There are also legal obstacles. In most states, houses built on a foundation must be at least 400 square feet. To get around that, builders have taken to putting tiny houses on wheels and building them to the less restrictive codes that apply to RVs. But many states and cities bar RVs from being parked in one place year-round. Also, when you buy a tiny house, the house is all you get; you have to either buy the land to put it on, use someone else’s for free, or find a landlord willing to lease land to you.

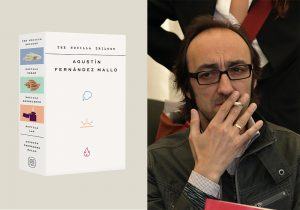

And yet the most surprising aspect of the tiny-house phenomenon might be that, while the lifestyle has never been more visible, real-life tiny-house dwellers are hard to find. Fewer than ten thousand of the homes are estimated to exist nationwide. The impracticalities of tiny living—shoebox-sized sinks, closetless rooms—can be daunting, but it’s not only that. There are also legal obstacles. In most states, houses built on a foundation must be at least 400 square feet. To get around that, builders have taken to putting tiny houses on wheels and building them to the less restrictive codes that apply to RVs. But many states and cities bar RVs from being parked in one place year-round. Also, when you buy a tiny house, the house is all you get; you have to either buy the land to put it on, use someone else’s for free, or find a landlord willing to lease land to you. In June 2007, in Seville, Spain, a conference was held under the banner “New Fictioneers: The Spanish Literary Atlas.” Around forty writers and critics came together at the Andalusian Center for Contemporary Art to discuss the conservatism they felt to be suffocating their national literature. United in their belief that the Spanish novel in particular was in a bad state, they pointed to a disregard for the increasing centrality of digital media in people’s lives and a knee-jerk resistance to anything that smacked of formal experimentation. They were mostly of a similar age, born in the twilight of the Franco regime, committed to the DIY punk ethos of the fledgling blogosphere, and more likely to claim lineage to J. G. Ballard or Jean Baudrillard than any garlanded compatriots of their own. Nonetheless, the only true point of agreement on the day was that they were not part of a unified movement. The conference’s inaugural address itself rejected any suggestion of a coherent generation—a commonplace criticism familiar in Spain ever since the clumping together, at the end of the nineteenth century, of the Generation of ’98. Within a few weeks, however, an article appeared dubbing these writers “The Nocilla Generation”: the most significant literary phenomenon of Spain’s democratic era now had a label, and it stuck.

In June 2007, in Seville, Spain, a conference was held under the banner “New Fictioneers: The Spanish Literary Atlas.” Around forty writers and critics came together at the Andalusian Center for Contemporary Art to discuss the conservatism they felt to be suffocating their national literature. United in their belief that the Spanish novel in particular was in a bad state, they pointed to a disregard for the increasing centrality of digital media in people’s lives and a knee-jerk resistance to anything that smacked of formal experimentation. They were mostly of a similar age, born in the twilight of the Franco regime, committed to the DIY punk ethos of the fledgling blogosphere, and more likely to claim lineage to J. G. Ballard or Jean Baudrillard than any garlanded compatriots of their own. Nonetheless, the only true point of agreement on the day was that they were not part of a unified movement. The conference’s inaugural address itself rejected any suggestion of a coherent generation—a commonplace criticism familiar in Spain ever since the clumping together, at the end of the nineteenth century, of the Generation of ’98. Within a few weeks, however, an article appeared dubbing these writers “The Nocilla Generation”: the most significant literary phenomenon of Spain’s democratic era now had a label, and it stuck.