Fifteen influencers weigh in on the company’s 15th birthday in Vox:

Jonathan Haidt, author of The Coddling of the American Mind and professor at NYU

Jonathan Haidt, author of The Coddling of the American Mind and professor at NYU

There’s an old joke about an optimist who fell off of the observation deck of the Empire State Building. As he was passing the 30th floor someone called out to him: “How’s it going?” He replied: “So far, so good!” I think that joke has some relevance for humanity in the Facebook era. So far, the billions of small positive effects of massively increasing human interconnectivity may well outweigh the growing roster of negatives, large and small. Yet when I look to the future, I see two giant negative effects looming larger and larger, like the pavement rushing up to the optimistic jumper.

First, rates of depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicide are rising rapidly in young people born after 1995 — “Gen Z” — which has largely been on social-media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat since middle school. This rise in mood disorders is not happening in all countries, but it is happening — particularly to girls — in the US, the UK, and Canada. There are empirical studies pointing to a causal connection to heavy social media use, and there are studies indicating no connection. I predict that a consensus will emerge by the end of 2019, and that it will be that heavy use of social media damages many young teenage girls, reducing their odds of success in life.

The second potentially gigantic problem is that large, diverse, secular democracies are inherently unstable, inherently prone to division unless there are sufficient “centripetal” forces pulling toward the center (such as having a shared language, shared rituals and values, and high trust in the basic political and economic institutions of the country).

Facebook and other social media platforms are powerful centrifugal forces, binding groups together to fight other groups within their own country, driven mad and propelled into battle by an eternal mudslide of outrage-inducing viral videos and conspiracy theories. We are already seeing these effects in many countries.

More here.

“If you really want to erase or distort a story,” Khaled Khalifa declares in his astonishing new novel “Death Is Hard Work,” “you should turn it into several different stories with different endings and plenty of incidental details.” He’s referring to the salutary comforts of narrative. This — or so we like to reassure ourselves — is one reason we turn to literature: as a balm, an expression of the bonds that bring us together, rather than the divisions that tear us apart.

“If you really want to erase or distort a story,” Khaled Khalifa declares in his astonishing new novel “Death Is Hard Work,” “you should turn it into several different stories with different endings and plenty of incidental details.” He’s referring to the salutary comforts of narrative. This — or so we like to reassure ourselves — is one reason we turn to literature: as a balm, an expression of the bonds that bring us together, rather than the divisions that tear us apart.

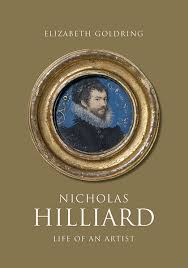

According to Elizabeth Goldring in this engrossing biography, the earliest recorded use of the term ‘miniature’ in English literature comes in Sir Philip Sidney’s prose romance The New Arcadia, written in the early 1580s. Four ladies bathe and splash playfully in the River Ladon, personified as male, and he responds delightedly by making numerous bubbles, as if ‘he would in each of those bubbles set forth the miniature of them’. It’s a pleasing image, calling to mind the delicacy and radiance of the works of Nicholas Hilliard, the leading miniaturist (or ‘limner’) of the Elizabethan age, whom Sidney knew and with whom he discussed emerging ideas about the theory and practice of art. In some ways, a miniature had the ephemerality of a bubble, capturing an individual at a fleeting moment in time, often recorded in an inscription noting the date and the sitter’s age. Yet it also made that moment last for posterity, as shown in this sumptuous book, where Hilliard’s subjects gaze back at us piercingly from many of the 250 colour illustrations.

According to Elizabeth Goldring in this engrossing biography, the earliest recorded use of the term ‘miniature’ in English literature comes in Sir Philip Sidney’s prose romance The New Arcadia, written in the early 1580s. Four ladies bathe and splash playfully in the River Ladon, personified as male, and he responds delightedly by making numerous bubbles, as if ‘he would in each of those bubbles set forth the miniature of them’. It’s a pleasing image, calling to mind the delicacy and radiance of the works of Nicholas Hilliard, the leading miniaturist (or ‘limner’) of the Elizabethan age, whom Sidney knew and with whom he discussed emerging ideas about the theory and practice of art. In some ways, a miniature had the ephemerality of a bubble, capturing an individual at a fleeting moment in time, often recorded in an inscription noting the date and the sitter’s age. Yet it also made that moment last for posterity, as shown in this sumptuous book, where Hilliard’s subjects gaze back at us piercingly from many of the 250 colour illustrations. When we meet Julie Yip-Williams at the beginning of “The Unwinding of the Miracle,” her eloquent, gutting and at times disarmingly funny memoir, she has already died, having succumbed to colon cancer in March 2018 at the age of 42, leaving behind her husband and two young daughters. And so she joins the recent spate of debuts from dead authors, including Paul Kalanithi and Nina Riggs, who also documented their early demises. We might be tempted to assume that these books were written mostly for the writers themselves, as a way to make sense of a frightening diagnosis and uncertain future; or for their families, as a legacy of sorts, in order to be known more fully while alive and kept in mind once they were gone.

When we meet Julie Yip-Williams at the beginning of “The Unwinding of the Miracle,” her eloquent, gutting and at times disarmingly funny memoir, she has already died, having succumbed to colon cancer in March 2018 at the age of 42, leaving behind her husband and two young daughters. And so she joins the recent spate of debuts from dead authors, including Paul Kalanithi and Nina Riggs, who also documented their early demises. We might be tempted to assume that these books were written mostly for the writers themselves, as a way to make sense of a frightening diagnosis and uncertain future; or for their families, as a legacy of sorts, in order to be known more fully while alive and kept in mind once they were gone. A writer’s life and work are not a gift to mankind; they are its necessity,” says

A writer’s life and work are not a gift to mankind; they are its necessity,” says  Unlikely as it might sound, one of the most electric political meetings I have ever attended was a lecture on the Finnish educational system given by

Unlikely as it might sound, one of the most electric political meetings I have ever attended was a lecture on the Finnish educational system given by  T

T AROUND 2014

AROUND 2014 Amid the global rise of the Christian right, some

Amid the global rise of the Christian right, some  Bolz-Weber had flown in from her home in Denver to promote her book “

Bolz-Weber had flown in from her home in Denver to promote her book “ In 1972 the socialist left swept to power in Jamaica. Calling for the strengthening of workers’ rights, the nationalization of industries, and the expansion of the island’s welfare state, the People’s National Party (PNP), led by the charismatic Michael Manley, sought nothing less than to overturn the old order under which Jamaicans had long labored—first as enslaved, then indentured, then colonized, and only recently as politically free of Great Britain. Jamaica is a small island, but the ambition of the project was global in scale.

In 1972 the socialist left swept to power in Jamaica. Calling for the strengthening of workers’ rights, the nationalization of industries, and the expansion of the island’s welfare state, the People’s National Party (PNP), led by the charismatic Michael Manley, sought nothing less than to overturn the old order under which Jamaicans had long labored—first as enslaved, then indentured, then colonized, and only recently as politically free of Great Britain. Jamaica is a small island, but the ambition of the project was global in scale. To those convinced that a secretive cabal controls the world, the usual suspects are Illuminati, Lizard People, or “globalists.” They are wrong, naturally. There is no secret society shaping every major decision and determining the direction of human history. There is, however, McKinsey & Company.

To those convinced that a secretive cabal controls the world, the usual suspects are Illuminati, Lizard People, or “globalists.” They are wrong, naturally. There is no secret society shaping every major decision and determining the direction of human history. There is, however, McKinsey & Company. A couple of months ago, Twitter user @emrazz asked women

A couple of months ago, Twitter user @emrazz asked women  An army unit known as the “Six Triple Eight” had a specific mission in

An army unit known as the “Six Triple Eight” had a specific mission in  Jonathan Haidt, author of The Coddling of the American Mind and professor at NYU

Jonathan Haidt, author of The Coddling of the American Mind and professor at NYU IN A SERIES

IN A SERIES  Grime music is catharsis delivered from a vertiginous height. Born and bred in London’s inner city housing projects in the early 2000’s, among a Black youth subculture that drew more on Jamaican reggae than American rap, grime was a product of confinement. London’s social housing tower blocks, in which many of grime’s pioneers grew up, became synonymous with the genre’s grittiness and hyperlocal roots, but they were also essential to the music’s distribution. Grime was first popularized by pirate radio stations broadcast from illegal transmitters and squatted “studios” erected on the rooftops of 20- and 30-story buildings. Up there, elevated from their impoverished upbringings, grime’s founders found space to breathe. What they created was unapologetically strange and uncompromising: music built from beats too irregular to dance to, rapping too fast to be intelligible on the radio, lyrics full of niche slang and swear words, and songs not geared around hooks and choruses. Moreover, all of this was produced by artists unwilling to play with a British music industry focused on developing homegrown guitar bands and importing rap and R&B from the United States.

Grime music is catharsis delivered from a vertiginous height. Born and bred in London’s inner city housing projects in the early 2000’s, among a Black youth subculture that drew more on Jamaican reggae than American rap, grime was a product of confinement. London’s social housing tower blocks, in which many of grime’s pioneers grew up, became synonymous with the genre’s grittiness and hyperlocal roots, but they were also essential to the music’s distribution. Grime was first popularized by pirate radio stations broadcast from illegal transmitters and squatted “studios” erected on the rooftops of 20- and 30-story buildings. Up there, elevated from their impoverished upbringings, grime’s founders found space to breathe. What they created was unapologetically strange and uncompromising: music built from beats too irregular to dance to, rapping too fast to be intelligible on the radio, lyrics full of niche slang and swear words, and songs not geared around hooks and choruses. Moreover, all of this was produced by artists unwilling to play with a British music industry focused on developing homegrown guitar bands and importing rap and R&B from the United States. A crisis of this magnitude almost invariably reveals wider dysfunctions, and so it has been with Macron’s debacle with the gilets jaunes. The President seemed oblivious to the plight of the provinces, and unable to show any personal empathy with the lives of ordinary citizens. Visiting all corners of the territory and making an emotional connection with the people are key functions of the French republican monarch. De Gaulle managed this with his systematic tournées across small towns and villages: by the end of his first term, he had visited every metropolitan département. The very incarnation of this esprit de proximité was Jacques Chirac, who genuinely delighted in his encounters with the public, especially when they afforded opportunities to sample tasty local victuals. Macron, in contrast, has failed to cultivate these organic (and gastronomical) ties with the citizenry. He has also communicated very patchily, with long periods of Olympian silence combined with clumsy off-the-cuff interventions – as when he grumbled about his compatriots’ “Gaulois tendency to resist change”, or when he told an unemployed man that he could find a job by “just crossing the street”. In his December 10 speech, he expressed his sorrow for having “hurt” the French people by “some of his words”, and for seeming “indifferent” to their everyday concerns. This is one of the areas where his combination of intellectual superiority and political inexperience – he never held elected office before becoming President – have come back to haunt him.

A crisis of this magnitude almost invariably reveals wider dysfunctions, and so it has been with Macron’s debacle with the gilets jaunes. The President seemed oblivious to the plight of the provinces, and unable to show any personal empathy with the lives of ordinary citizens. Visiting all corners of the territory and making an emotional connection with the people are key functions of the French republican monarch. De Gaulle managed this with his systematic tournées across small towns and villages: by the end of his first term, he had visited every metropolitan département. The very incarnation of this esprit de proximité was Jacques Chirac, who genuinely delighted in his encounters with the public, especially when they afforded opportunities to sample tasty local victuals. Macron, in contrast, has failed to cultivate these organic (and gastronomical) ties with the citizenry. He has also communicated very patchily, with long periods of Olympian silence combined with clumsy off-the-cuff interventions – as when he grumbled about his compatriots’ “Gaulois tendency to resist change”, or when he told an unemployed man that he could find a job by “just crossing the street”. In his December 10 speech, he expressed his sorrow for having “hurt” the French people by “some of his words”, and for seeming “indifferent” to their everyday concerns. This is one of the areas where his combination of intellectual superiority and political inexperience – he never held elected office before becoming President – have come back to haunt him. In 724 A.D., the twenty-three-year-old poet Li Bai got on a boat and set out from his home region of Shu, today’s Sichuan province, in search of Daoist learnings and a political career. He wasn’t headed anywhere in particular. Instead, he began a life of roaming—hiking up mountains to Daoist sites, meeting men of letters all over the country, and leaving behind hundreds of poems about his travels, his solitude, his friends, the moon, and the pleasures of drinking wine. In the centuries since, Li’s verse, by turns playful and profound, has made him China’s most beloved poet.

In 724 A.D., the twenty-three-year-old poet Li Bai got on a boat and set out from his home region of Shu, today’s Sichuan province, in search of Daoist learnings and a political career. He wasn’t headed anywhere in particular. Instead, he began a life of roaming—hiking up mountains to Daoist sites, meeting men of letters all over the country, and leaving behind hundreds of poems about his travels, his solitude, his friends, the moon, and the pleasures of drinking wine. In the centuries since, Li’s verse, by turns playful and profound, has made him China’s most beloved poet.