by Jonathan Kujawa

This spring I attended the annual meeting of the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute. While there I heard a fantastic talk by Dr. Holly Krieger about which I'd like to tell you. If you'd like to hear Dr. Krieger tell you herself, I highly recommend the Numberphile video she hosted. You can see it here.

This spring I attended the annual meeting of the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute. While there I heard a fantastic talk by Dr. Holly Krieger about which I'd like to tell you. If you'd like to hear Dr. Krieger tell you herself, I highly recommend the Numberphile video she hosted. You can see it here.

Dr. Krieger works in the area of dynamic systems. Faithful 3QD readers will remember that we ran into this topic a few months ago when we talked about the Collatz conjecture and the mathematics of billiards (see here). Dynamical systems is the field which studies systems (the weather, the stock market, the hands on a clock, a ball ricocheting around a billiard table) which changes over time according to some rule.

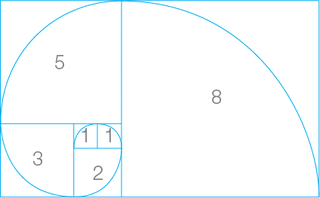

A seemingly simple example of this is the Fibonacci sequence. You probably saw it as kid:

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765, 10946, 17711, 28657, 46368, 75025, 121393, 196418, 317811, 514229, 832040, 1346269,….

This is the sequence of numbers which starts with a 0 and 1, and then each subsequent number is the sum of the previous two: 0+1=1, 1+1=2, 1+2=3, 2+3=5, etc. To a mathematician this is a dynamical system. We can think of the nth number in the sequence as the state of the system after n seconds and the addition rule tells us how the system changes from one second to the next.

Last time we talked about dynamical systems we were interested in the question of whether such a system ever returns to its starting state. A properly working clock always ends up back where it was twenty-four hours ago. At the other extreme, the stock market will never end up back in the exact same state. Somewhere in the middle we have the billiard ball. It may or may not return, depending on the shape of the table and where you start the ball.

From this point of view the Fibonacci sequence is boring as all get out. It just gets bigger and bigger forever. But Dr. Krieger is the sort who isn't satisfied with such an answer. She asks questions like: You get a new number every time, but is it really “new” or “mostly old” [1]?

What do I mean? Well, we first need to recall the prime numbers. These are numbers like 2, 3, 5, and 7 which can't be evenly divided by another number (except 1 and itself, of course). On the other hand, 4, 6, 8, and 9 are not prime as they can be divided by 2's and 3's. That is, a non-prime can be written as a product of other numbers (like 24=4×6). If you keep subdividing you can eventually write any number as product of primes (like 24=2x2x2x3).

You should think of the prime numbers as the atoms of numbers: every number can be broken down into primes and you can't go any further. To stretch the analogy a little further, most folks are more excited when you discover a new atomic element than if you “just” discover a new combination of old elements. In the same spirit, you might think to ask if the Fibonacci sequence is made up of a few primes used over and over (like using 2 and 3 to make 6, 9, 12, 18, and 864), or if new primes are used as you go along.

Read more »

Gil Anidjar in a forum remembering Derrida at the LA Review of Books: