by Dave Maier

Most philosophical chestnuts leave me cold. Their standard formulations usually have some confusion or preconception or equivocation in there somewhere, so that even when the original puzzle makes sense, the real philosophical action has moved on, often to places unrecognizable to the layman (for good or ill). Take the one about whether, when a tree falls in the forest with no one around to hear, it makes a sound. (According to a recent TV ad, yes, to wit: “Aaaagh! [*wham*] … little help? Anyone? Hello?”) My answer: it depends on what you mean by “sound”; in one sense, yes, in another, no. Both uses of the term are perfectly well established – you just can't use them interchangeably. There are of course some live philosophical questions about perception and reality to keep us busy; this just isn't one of them.

Most philosophical chestnuts leave me cold. Their standard formulations usually have some confusion or preconception or equivocation in there somewhere, so that even when the original puzzle makes sense, the real philosophical action has moved on, often to places unrecognizable to the layman (for good or ill). Take the one about whether, when a tree falls in the forest with no one around to hear, it makes a sound. (According to a recent TV ad, yes, to wit: “Aaaagh! [*wham*] … little help? Anyone? Hello?”) My answer: it depends on what you mean by “sound”; in one sense, yes, in another, no. Both uses of the term are perfectly well established – you just can't use them interchangeably. There are of course some live philosophical questions about perception and reality to keep us busy; this just isn't one of them.

Naturally this isn't enough for some people. The answer is “merely semantic,” and doesn't engage the real mystery of subjects in an objective world. The other questions about perception I mentioned – where for my money the “real action” is – don't give us that same buzz. They're boring, technical, overly analytic. Worse, their focus is disappointingly narrow. Whatever the fate of, say, the doctrine of epistemological disjunctivism, we're a long way from the wonder in which philosophy supposedly begins. Whatever happened, these people ask, to the quest for the True, the Good, and the Beautiful?

My own response to this is that if we just keep our eyes on the true (in inquiry), the good (in action), and the beautiful (in lots of places), then the all-caps TGB (whatever, if anything, they turn out to be) can take care of themselves. But other philosophers – let's call them “naturalists” – take a more actively deflationary line against what they see as mystical obscurantism. If there are any mysteries here, they are scientific mysteries, best answered with the no-nonsense tools of empiricial science; and philosophy's task is not to try to deal with these questions itself, but just to clear the way for science. To do otherwise, according to naturalists, leads to metaphysics – or worse, theology.

If we get all that from just the tree in the forest, imagine what happens when our question is the greatest chestnut of them all: why is there anything at all, instead of nothing? Here a theological answer is so close you can taste it – and whether that taste be yummy or foul, that tends to be what underlies the more contentious answers to our question. To the main combatants, who think it of such monumental importance, there doesn't seem to be any room between naturalism and metaphysics.

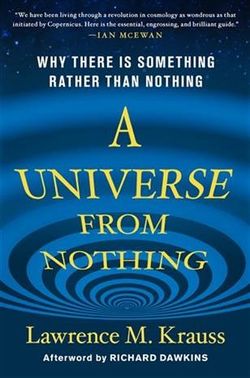

I bring this up today not because I have suddenly developed a philosophical interest in this question (that is, the chestnut itself), but instead because I have just begun physicist Lawrence Krauss's 2012 book A Universe From Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather than Nothing, which comes down firmly on the naturalist side, and I'm already not appreciating the characteristic naturalist tendency to run together resistance to naturalism, on the one hand, with creationism/theology/metaphysics (along with right-wing politics and who knows what else) on the other. (Nor do I accept the converse identification, made by the TGB brigade, of resistance to their metaphysical project, on the one hand, with a nihilistic “scientism” on the other.) My kind of philosopher tends to ignore this particular chestnut completely, so it's not surprising that our sensibility is not well represented in these discussions, but I'd like to get a couple of cents in if I may.

Read more »