by Michael Liss

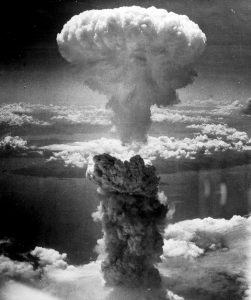

Will you know what to do when the atomic bomb drops? This question, and others like it, are vividly on display in the 4K restoration of Jayne Loader, Kevin Rafferty, and Pierce Rafferty’s 1982 documentary, The Atomic Café. Having seen the movie when it was first released (my kids’ reaction to this information was “of course you did”) I was determined to return to my roots. But, this being 2018, I took full advantage of technologies not available in the Neolithic Age: I quickly went online and bought two tickets for a night when the filmmakers themselves would be there for a Q&A. Then I fired off a few text messages to friendly liberals of a similar vintage to see who else was going, because you really don’t go to one of these things without a posse.

Will you know what to do when the atomic bomb drops? This question, and others like it, are vividly on display in the 4K restoration of Jayne Loader, Kevin Rafferty, and Pierce Rafferty’s 1982 documentary, The Atomic Café. Having seen the movie when it was first released (my kids’ reaction to this information was “of course you did”) I was determined to return to my roots. But, this being 2018, I took full advantage of technologies not available in the Neolithic Age: I quickly went online and bought two tickets for a night when the filmmakers themselves would be there for a Q&A. Then I fired off a few text messages to friendly liberals of a similar vintage to see who else was going, because you really don’t go to one of these things without a posse.

I was not to be disappointed. Six of us converged on the newly renovated, but still decidedly funky Film Forum. First, my 26-year old son, who spared me the dubious honor of being the only person in the audience in a suit, white shirt, and dark tie (we looked like refugees from a Book of Mormon casting call). Then four of the like-minded, three of whom could be described as gracefully aging hipsters (wearing, respectively, a pair of gray braids, a great-looking gray Van Dyke, and a graying inside out T-shirt) and finally, my pal (and liberal conscience) Melinda.

I could write books about Melinda, and I should, because there aren’t enough Melindas in the world. She’s a Yellow Dog Texas Democrat who brought with her to New York an indestructible accent, an odd affinity for driving minivans as basic transportation in a car-unfriendly city, and an inexhaustible capacity for good works. If there was a protest anywhere, Melinda knew about it, probably organized it, and occasionally got arrested for it. There are still places that are off-limits to her, for a variety of Deep State-ish reasons. Greenwich Village, of course, is not one of them. Melinda is the genuine article.

But I digress. The movie is the thing you came to see, and the movie is what you should get. Read more »

Even as we want to do the right thing, we may wonder if there is “really” a right thing to do. Through most of the twentieth-century most Anglo-American philosophers were some sort of subjectivist or other. Since they focused on language, the way that they tended to put it was something like this. Ethical statements look like straight-forward propositions that might be true or false, but in fact they are simply expressions or descriptions of our emotions or preferences. J.L. Mackie’s “error-theory” version, for example, implied that when I say ‘Donald Trump is a horrible person’ what I really mean is ‘I don’t like Donald Trump’. If we really believed that claims about what is right or wrong, good or bad, or just or unjust, were just subjective expressions of our own idiosyncratic emotions and desires, then our shared public discourse, and our shared public life, obviously, would look very different. One of Nietzsche’s “terrible truths” is that most of our thinking about right and wrong is just a hangover from Christianity that will eventually dissipate. We are like the cartoon character who has gone over a cliff but is not yet falling only because we haven’t looked down. Yet.

Even as we want to do the right thing, we may wonder if there is “really” a right thing to do. Through most of the twentieth-century most Anglo-American philosophers were some sort of subjectivist or other. Since they focused on language, the way that they tended to put it was something like this. Ethical statements look like straight-forward propositions that might be true or false, but in fact they are simply expressions or descriptions of our emotions or preferences. J.L. Mackie’s “error-theory” version, for example, implied that when I say ‘Donald Trump is a horrible person’ what I really mean is ‘I don’t like Donald Trump’. If we really believed that claims about what is right or wrong, good or bad, or just or unjust, were just subjective expressions of our own idiosyncratic emotions and desires, then our shared public discourse, and our shared public life, obviously, would look very different. One of Nietzsche’s “terrible truths” is that most of our thinking about right and wrong is just a hangover from Christianity that will eventually dissipate. We are like the cartoon character who has gone over a cliff but is not yet falling only because we haven’t looked down. Yet. Our first act of communication is to look in each other’s eyes, or not to. Many descriptors center subtly on the gaze: I might be shifty if I’m looking away from you too often and too purposefully, diffident if I cast downward when I ought to be looking you in the eyes, or unsettling if I never stop looking at you.

Our first act of communication is to look in each other’s eyes, or not to. Many descriptors center subtly on the gaze: I might be shifty if I’m looking away from you too often and too purposefully, diffident if I cast downward when I ought to be looking you in the eyes, or unsettling if I never stop looking at you.

In the science fiction short story “

In the science fiction short story “

The major “National-Socialist Underground” trial

The major “National-Socialist Underground” trial  The ill-defined term ‘populism’ is used in different senses not just by common people or the media, but even among social scientists. Economists usually interpret it as short-termism at the expense of the long-term health of the economy. They usually refer to it in describing macro-economic profligacy, leading to galloping budget deficits in pandering to all kinds of pressure groups for larger government spending and to the consequent inflation—examples abound in the recent history of Latin America (currently in virulent display in Venezuela). Political scientists, on the other hand, refer to the term in the context of a certain widespread distrust in the institutions of representative democracy, when people look for a strong leader who can directly embody the ‘popular will’ and cut through the tardy processes of the rule of law and encumbrances like basic human rights or minority rights. Even though I am an economist, in this article I shall mainly confine myself to the latter use of the term.

The ill-defined term ‘populism’ is used in different senses not just by common people or the media, but even among social scientists. Economists usually interpret it as short-termism at the expense of the long-term health of the economy. They usually refer to it in describing macro-economic profligacy, leading to galloping budget deficits in pandering to all kinds of pressure groups for larger government spending and to the consequent inflation—examples abound in the recent history of Latin America (currently in virulent display in Venezuela). Political scientists, on the other hand, refer to the term in the context of a certain widespread distrust in the institutions of representative democracy, when people look for a strong leader who can directly embody the ‘popular will’ and cut through the tardy processes of the rule of law and encumbrances like basic human rights or minority rights. Even though I am an economist, in this article I shall mainly confine myself to the latter use of the term. When Mrs. William Shakespeare died on this August day in 1623, her family and friends believed they would lay her to eternal rest beside her renowned husband. They did not. They did inter an ordinary wife and mother, but the memory of her went out to become a Frankenstein monster, cut up and reassembled down the centuries. Few of the many makeovers done to Anne Hathaway Shakespeare since her passing have been flattering.

When Mrs. William Shakespeare died on this August day in 1623, her family and friends believed they would lay her to eternal rest beside her renowned husband. They did not. They did inter an ordinary wife and mother, but the memory of her went out to become a Frankenstein monster, cut up and reassembled down the centuries. Few of the many makeovers done to Anne Hathaway Shakespeare since her passing have been flattering.

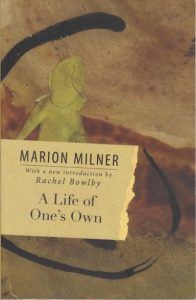

I’m tempted to describe Marion Milner’s book A Life of One’s Own as the missing manual for owners of a human mind. However, it’s not didactic or prescriptive. In fact, it’s useful mainly because it’s nothing like a manual or a self-help book. The book is more like an insightful travelogue by an articulate and honest observer with a gift for using vivid physical imagery and metaphors to describe her inner world.

I’m tempted to describe Marion Milner’s book A Life of One’s Own as the missing manual for owners of a human mind. However, it’s not didactic or prescriptive. In fact, it’s useful mainly because it’s nothing like a manual or a self-help book. The book is more like an insightful travelogue by an articulate and honest observer with a gift for using vivid physical imagery and metaphors to describe her inner world.