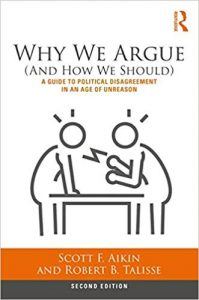

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

The second edition of our Why We Argue (And How We Should) is set to be released this month. The new edition is an update of the previous 2014 edition, and in particular, it is occasioned by the argumentative events leading up to and subsequent to the 2016 US Presidential election. New forms of fallacy needed to be diagnosed, and different strategies for their correction had to be posed. But we also saw that another element of a book on critical thinking and politics was necessary, one that has been all-too-often left out: a program for argument-repair. We looked at strategies for finding out what arguers are trying to say, what motivates them, and how to address not just the things argued, but the things that drive us to argue. We think that very often, repairing an argument requires repairing the culture of argument.

One reason why arguments go so badly is because the disagreement and interplay between us, our interlocutors, and our onlooking audiences starts off as fraught. And so, further exchange often makes things worse instead of better. We call this phenomenon argument escalation. Again, we’ve all seen it happen — a difference of opinion about some small matter grows into an argument, an argument becomes a verbal fight, and the verbal fight becomes a fight involving more than merely words. And it’s worse when there are onlookers who will judge us and our performances. Half of the time, we want to stop it all and say, “We are all grownups here . . . can’t we just calm down?” But were one to say this, the interlocutor is liable to respond, “Are you calling me a child, then? And don’t tell me to calm down!” How can we repair arguments without further escalating them? Read more »

The dangers of climate change pose a threat to all of humankind and to ecosystems all over the world. Does this mean that all humans need to equally shoulder the responsibility to mitigate climate change and its effects? The concept of CBDR (common but differentiated responsibilities) is routinely discussed at international negotiations about climate change mitigation. The basic principle of CBDR in the context of climate change is that highly developed countries have historically contributed far more than to climate change and therefore need to reduce their carbon footprint far more than less developed countries. The per capita rate of vehicles in the United States is approximately 90 cars per 100 people, whereas the rate in India is 5 cars per 100 people. The total per capita carbon footprint includes a plethora of factors such as carbon emissions derived from industry, air travel and electricity consumption of individual households. As of 2015, the

The dangers of climate change pose a threat to all of humankind and to ecosystems all over the world. Does this mean that all humans need to equally shoulder the responsibility to mitigate climate change and its effects? The concept of CBDR (common but differentiated responsibilities) is routinely discussed at international negotiations about climate change mitigation. The basic principle of CBDR in the context of climate change is that highly developed countries have historically contributed far more than to climate change and therefore need to reduce their carbon footprint far more than less developed countries. The per capita rate of vehicles in the United States is approximately 90 cars per 100 people, whereas the rate in India is 5 cars per 100 people. The total per capita carbon footprint includes a plethora of factors such as carbon emissions derived from industry, air travel and electricity consumption of individual households. As of 2015, the

A number of scenes in Eugene Zamyatin’s dystopian novel

A number of scenes in Eugene Zamyatin’s dystopian novel

The link to Charles McGrath’s ‘No Longer Writing, Philip Roth Still Has Plenty to Say’ which appeared in the New York Times in January, only a few months prior to Roth’s death in May this year, was forwarded to me by a friend who thought I might find the article interesting. How indebted I am to my friend that he thought of me in those terms, for the sending of that article rekindled my acquaintance with Roth; life’s events and circumstances had left my reading of his work to the margins.

The link to Charles McGrath’s ‘No Longer Writing, Philip Roth Still Has Plenty to Say’ which appeared in the New York Times in January, only a few months prior to Roth’s death in May this year, was forwarded to me by a friend who thought I might find the article interesting. How indebted I am to my friend that he thought of me in those terms, for the sending of that article rekindled my acquaintance with Roth; life’s events and circumstances had left my reading of his work to the margins.

The past years have seen many debates about the limits of science. These debates are often phrased in the terminology of scientism, or in the form of a question about the status of the humanities. Scientism is a

The past years have seen many debates about the limits of science. These debates are often phrased in the terminology of scientism, or in the form of a question about the status of the humanities. Scientism is a  The career of Kenneth Widmerpool defined an era of British social and cultural life spanning most of the 20th century. He is fictional – a character in

The career of Kenneth Widmerpool defined an era of British social and cultural life spanning most of the 20th century. He is fictional – a character in

It’s a Saturday in May. I’m 17, and I’ve spent the morning washing and waxing my first car, a 1974 Gremlin. I’m so delighted that I drive around the block, windows down, Chuck Mangione playing on the radio. Feels so good, indeed. I’ve successfully negotiated a crucial passage on the road to adulthood, and I’m pleased with myself and my little car. Times change, though, and sometimes even people change. Forty years later, with, I hope, many miles ahead of me, I sold what I expect to be my last car.

It’s a Saturday in May. I’m 17, and I’ve spent the morning washing and waxing my first car, a 1974 Gremlin. I’m so delighted that I drive around the block, windows down, Chuck Mangione playing on the radio. Feels so good, indeed. I’ve successfully negotiated a crucial passage on the road to adulthood, and I’m pleased with myself and my little car. Times change, though, and sometimes even people change. Forty years later, with, I hope, many miles ahead of me, I sold what I expect to be my last car. I like playing Scrabble, and part of the reason is creating new words. That and the smack talk. I played a game with the swain of the day decades ago, and he challenged my word, which was not in and of itself surprising. As you may recall, if you lose a challenge, you lose a turn. With stakes so stupendously high, you mount a vigorous defense. I ended up losing the battle (and probably won the war) and thought no more of it. The ex-boyfriend brought it up a few years ago; I think he has put that on-the-spot coinage next to a picture of me in his mind. It is a shame that the word he will forever associate with me is “beardful.”

I like playing Scrabble, and part of the reason is creating new words. That and the smack talk. I played a game with the swain of the day decades ago, and he challenged my word, which was not in and of itself surprising. As you may recall, if you lose a challenge, you lose a turn. With stakes so stupendously high, you mount a vigorous defense. I ended up losing the battle (and probably won the war) and thought no more of it. The ex-boyfriend brought it up a few years ago; I think he has put that on-the-spot coinage next to a picture of me in his mind. It is a shame that the word he will forever associate with me is “beardful.”