by Thomas O’Dwyer

As Valentine’s Day fades away and the world returns to slippery gender normality, many Western men may still have some nagging questions. What did I do wrong this time? What do women want? Are we still on trial here? Older men may mutter that the male half of the young population has changed from manly men into little boys lost. Well, they have no one to blame but themselves. After centuries of entitled domination, some loutish cockerels have come home to roost. If manhood is on trial, it is for the bad attitudes, and worse, which it has long meted out to the other half of the population. Women are revolting only because male behaviour has been so revolting.

Yet, female rebellion is neither as new nor as rare as one might imagine. Women have often risen up against that most macho of male hobbies – warfare. The most famous example was the sex strike in the ancient Greek comedy Lysistrata by Aristophanes. Led by Lysistrata, the women withhold sex from their husbands as a strategy to end the Peloponnesian War.

In a modern re-enactment in 2003, Leymah Gbowee and the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace organized protests that included a sex strike. They brought peace to Liberia after a 14-year civil war and won the election of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the country’s first woman president. (Ms. Gbowee won the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize). Read more »

I don’t know how much you know about Petrarch. My guess is that you know him as a poet, primarily for his sonnets. Maybe you associate him with early Italian humanism and its reinvigorated dedication to the wisdom of classical Antiquity. Or perhaps you think of him as someone who expressed transcendental truths about the soul and its searching and wandering nature.

I don’t know how much you know about Petrarch. My guess is that you know him as a poet, primarily for his sonnets. Maybe you associate him with early Italian humanism and its reinvigorated dedication to the wisdom of classical Antiquity. Or perhaps you think of him as someone who expressed transcendental truths about the soul and its searching and wandering nature. History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events.

History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events. A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann)

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann) impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt?

impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt?

Like most people of a certain age, at any one time I have the unfortunate experience of knowing several people, some close, some not, who have cancer. It has become standard for the friend or spouse of the ill person to join one of the many message boards devoted to the subject and post updates to keep their friends and relatives informed. Others use Facebook to share information. Currently there are three people whose lives I follow, mostly from a distance, all with serious forms of cancer, one newly diagnosed but metastasized, two others who have been fighting for months and months.

Like most people of a certain age, at any one time I have the unfortunate experience of knowing several people, some close, some not, who have cancer. It has become standard for the friend or spouse of the ill person to join one of the many message boards devoted to the subject and post updates to keep their friends and relatives informed. Others use Facebook to share information. Currently there are three people whose lives I follow, mostly from a distance, all with serious forms of cancer, one newly diagnosed but metastasized, two others who have been fighting for months and months.

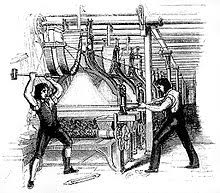

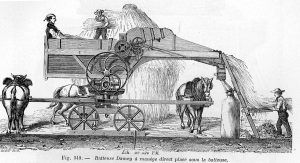

“Luddite” is a word that is thrown around a lot these days. It signifies someone who is opposed to technological progress, or who is at least not climbing on board the technological bandwagon. 21st century luddites tend to eschew social media, prefer presentations without PowerPoint, still write cheques, and may even, in extreme cases, get by without a cell phone. When used in the first person, “luddite” is often a badge of honour. “I’m a bit of a luddite,” usually means “I see through and am unimpressed by the false promise of constant technological novelty.” Used in the third person, though, it typically suggests criticism. “So-and-so’s a bit of a luddite,” is likely to imply that So-and-so finds the latest technology confusing and has failed to keep up with it, probably due to intellectual limitations.

“Luddite” is a word that is thrown around a lot these days. It signifies someone who is opposed to technological progress, or who is at least not climbing on board the technological bandwagon. 21st century luddites tend to eschew social media, prefer presentations without PowerPoint, still write cheques, and may even, in extreme cases, get by without a cell phone. When used in the first person, “luddite” is often a badge of honour. “I’m a bit of a luddite,” usually means “I see through and am unimpressed by the false promise of constant technological novelty.” Used in the third person, though, it typically suggests criticism. “So-and-so’s a bit of a luddite,” is likely to imply that So-and-so finds the latest technology confusing and has failed to keep up with it, probably due to intellectual limitations.

The traffic had been slow all day but by four pm, it was reduced to a trickle. Those cars that passed him on the street did so in two and threes as if they were sticking together for safety like lumbering animals caught out in a storm. It was, in fact, a very harsh winter day. The afternoon temperatures dipped well below zero: one of the coldest days ever recorded in Chicago. The only sounds now were from an occasional plane passing overhead, and from distant cackling from those venturesome neighbors who had left snug homes to experience the cold. He could hear the sound of his feet crunching through the snow.

The traffic had been slow all day but by four pm, it was reduced to a trickle. Those cars that passed him on the street did so in two and threes as if they were sticking together for safety like lumbering animals caught out in a storm. It was, in fact, a very harsh winter day. The afternoon temperatures dipped well below zero: one of the coldest days ever recorded in Chicago. The only sounds now were from an occasional plane passing overhead, and from distant cackling from those venturesome neighbors who had left snug homes to experience the cold. He could hear the sound of his feet crunching through the snow. One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism.

One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism.