Emily Joshu in Eating well:

Chances are, if you have put on a few pounds, the cause is deeper than eating too much junk food or skipping one too many workouts. Chronic, low-grade inflammation that swells in the body is to blame for this gain. And the relationship is cyclical. Weight and inflammation go hand in hand, and working to maintain a healthy weight through diet, exercise, sleep and stress management can help tame inflammatory markers as well.

Chances are, if you have put on a few pounds, the cause is deeper than eating too much junk food or skipping one too many workouts. Chronic, low-grade inflammation that swells in the body is to blame for this gain. And the relationship is cyclical. Weight and inflammation go hand in hand, and working to maintain a healthy weight through diet, exercise, sleep and stress management can help tame inflammatory markers as well.

Inflammation, however, comes in two varieties: acute and chronic. Most of us are accustomed to acute inflammation, such as after sustaining an injury. This temporary response doesn’t serve as a catalyst for serious health conditions but actually protects the body.

Chronic inflammation manifests as a slow burn in the body. “Inflammation is designed so once your body needs some healing, inflammation rushes in, but it’s only supposed to be short term. Chronic inflammation is more subtle, and it’s caused by irritation in the body,” says Carolyn Williams, Ph.D., R.D., author of Meals That Heal. “And that may be environmental things, that may be food-related things, that may be stress, that may be lack of sleep. Just about any kind of irritation to the body can trigger subtle inflammation.” Williams compares chronic inflammation to a fire in the body that will continue to grow without intervention. Research suggests that reducing chronic, low-grade inflammation may even be as crucial a component as diet and activity, Williams says. And the relationship goes both ways.

More here.

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by clicking here now? We wouldn’t ask for your support if we did not need it to keep the site running. And, of course, you will get the added benefit of no longer seeing any distracting ads on the site. Thank you!

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by clicking here now? We wouldn’t ask for your support if we did not need it to keep the site running. And, of course, you will get the added benefit of no longer seeing any distracting ads on the site. Thank you!

One of the courses I teach is called “Science, Activism, and Political Conflict,” and one of my ambitions with that course is to show students that both of these things—activism and political conflict—are normal in science, and in academic life more generally. That’s a theme that we like to emphasize when speaking in “defense” of student protest. It’s part of a storied tradition, it’s respectable, it’s normal. But in order to explain why I think what you all are doing is so important, I want to start today by saying that actually, student protest is nowhere near normal enough in the history of higher education in this country. The real scandal is not that there has been student protest. It is that there has not been much, much more of it.

One of the courses I teach is called “Science, Activism, and Political Conflict,” and one of my ambitions with that course is to show students that both of these things—activism and political conflict—are normal in science, and in academic life more generally. That’s a theme that we like to emphasize when speaking in “defense” of student protest. It’s part of a storied tradition, it’s respectable, it’s normal. But in order to explain why I think what you all are doing is so important, I want to start today by saying that actually, student protest is nowhere near normal enough in the history of higher education in this country. The real scandal is not that there has been student protest. It is that there has not been much, much more of it. An artificial intelligence system has proven it can save lives by warning physicians to check on patients whose heart test results indicate a high risk of dying. In a randomised clinical trial with almost 16,000 patients at two hospitals, the AI reduced overall deaths among high-risk patients by 31 per cent.

An artificial intelligence system has proven it can save lives by warning physicians to check on patients whose heart test results indicate a high risk of dying. In a randomised clinical trial with almost 16,000 patients at two hospitals, the AI reduced overall deaths among high-risk patients by 31 per cent. A Moloch Trap is, in simple terms, a zero-sum game. It explains a situation where participants compete for object or outcome X but make something else worse in the process. Everyone competes for X, but in doing so, everyone ends up worse off.

A Moloch Trap is, in simple terms, a zero-sum game. It explains a situation where participants compete for object or outcome X but make something else worse in the process. Everyone competes for X, but in doing so, everyone ends up worse off.

Many other fine pieces in the Central Exhibition are textile-based: a dense, earthy slab of threads by the Colombian Olga de Amaral, who turns ninety-two this year; a selection of embroidered burlap pieces by the anonymous Chileans known as Arpilleristas; large, cool compositions by Susanne Wenger, who spent most of her long life in Nigeria, practicing the Yoruba religion and mastering batik, the art of wax-resist dyeing. Her pieces, which show mortals and deities floating side by side, stick to the same spiky patterns and subdued hues but never retrace their steps; you could imagine them continuing forever, and might well want them to. If not, walk a few feet to the exhibition’s other main batik specialist, Ṣàngódáre Gbádégẹsin Àjàlá, who passed away in 2021. His creations are as religiously inclined as Wenger’s—he was her adopted son—but with a livelier clamor of bodies pressed together. There’s almost too much to savor; the intricate coloring, combined with pale spiderweb shading, gives the figures a pimpled texture I can’t remember seeing in art before and now can’t stop noticing everywhere. Àjàlá, Wenger, and the rest of the fibre brigade may be the snappiest retort to the gripe that there are too many dead artists this year: when we’re dealing with textiles, one of the oldest visual art forms and still backlogged with brilliance, the distinction between new and old stops mattering so much. Good is good, even if it takes decades for anyone to notice.

Many other fine pieces in the Central Exhibition are textile-based: a dense, earthy slab of threads by the Colombian Olga de Amaral, who turns ninety-two this year; a selection of embroidered burlap pieces by the anonymous Chileans known as Arpilleristas; large, cool compositions by Susanne Wenger, who spent most of her long life in Nigeria, practicing the Yoruba religion and mastering batik, the art of wax-resist dyeing. Her pieces, which show mortals and deities floating side by side, stick to the same spiky patterns and subdued hues but never retrace their steps; you could imagine them continuing forever, and might well want them to. If not, walk a few feet to the exhibition’s other main batik specialist, Ṣàngódáre Gbádégẹsin Àjàlá, who passed away in 2021. His creations are as religiously inclined as Wenger’s—he was her adopted son—but with a livelier clamor of bodies pressed together. There’s almost too much to savor; the intricate coloring, combined with pale spiderweb shading, gives the figures a pimpled texture I can’t remember seeing in art before and now can’t stop noticing everywhere. Àjàlá, Wenger, and the rest of the fibre brigade may be the snappiest retort to the gripe that there are too many dead artists this year: when we’re dealing with textiles, one of the oldest visual art forms and still backlogged with brilliance, the distinction between new and old stops mattering so much. Good is good, even if it takes decades for anyone to notice. Chances are, if you have put on a few pounds, the cause is deeper than eating too much junk food or skipping one too many workouts. Chronic, low-grade

Chances are, if you have put on a few pounds, the cause is deeper than eating too much junk food or skipping one too many workouts. Chronic, low-grade  In some birding circles, people say that anyone who looks at birds is a birder — a kind, inclusive sentiment that overlooks the forces that create and shape subcultures. Anyone can dance, but not everyone would identify as a dancer, because the term suggests, if not skill, then at least effort and intent. Similarly, I’ve cared about birds and other animals for my entire life, and I’ve written about them throughout my two decades as a science writer, but I mark the moment when I specifically chose to devote time and energy to them as the moment I became a birder.

In some birding circles, people say that anyone who looks at birds is a birder — a kind, inclusive sentiment that overlooks the forces that create and shape subcultures. Anyone can dance, but not everyone would identify as a dancer, because the term suggests, if not skill, then at least effort and intent. Similarly, I’ve cared about birds and other animals for my entire life, and I’ve written about them throughout my two decades as a science writer, but I mark the moment when I specifically chose to devote time and energy to them as the moment I became a birder. Few computer science breakthroughs have done so much in so little time as the artificial intelligence design known as a transformer. A transformer is a form of deep learning—a machine model based on networks in the brain—that researchers at Google

Few computer science breakthroughs have done so much in so little time as the artificial intelligence design known as a transformer. A transformer is a form of deep learning—a machine model based on networks in the brain—that researchers at Google  The system that evolved in the last quarter of the twentieth century on both sides of the Atlantic came to be called neoliberalism. “Liberal” refers to being “free,” in this context, free of government intervention including regulations. The “neo” meant to suggest that there was something new in it; in reality, it was little different from the liberalism and laissez-faire doctrines of the nineteenth century that advised: “leave it to the market.”

The system that evolved in the last quarter of the twentieth century on both sides of the Atlantic came to be called neoliberalism. “Liberal” refers to being “free,” in this context, free of government intervention including regulations. The “neo” meant to suggest that there was something new in it; in reality, it was little different from the liberalism and laissez-faire doctrines of the nineteenth century that advised: “leave it to the market.” I

I Suddenly, everyone is talking about aliens. After decades on the cultural margins, the question of life in the Universe beyond Earth is having its day in the sun. The next big multibillion-dollar space telescope (the successor to the James Webb) will be tuned to search for signatures of alien life on alien planets and NASA has a robust, well-funded programme in astrobiology. Meanwhile, from breathless newspaper articles about unexplained navy pilot sightings to United States congressional testimony with wild claims of government programmes hiding crashed saucers, UFOs and UAPs (unidentified anomalous phenomena) seem to be making their own journey from the fringes.

Suddenly, everyone is talking about aliens. After decades on the cultural margins, the question of life in the Universe beyond Earth is having its day in the sun. The next big multibillion-dollar space telescope (the successor to the James Webb) will be tuned to search for signatures of alien life on alien planets and NASA has a robust, well-funded programme in astrobiology. Meanwhile, from breathless newspaper articles about unexplained navy pilot sightings to United States congressional testimony with wild claims of government programmes hiding crashed saucers, UFOs and UAPs (unidentified anomalous phenomena) seem to be making their own journey from the fringes. Because the likelihood of

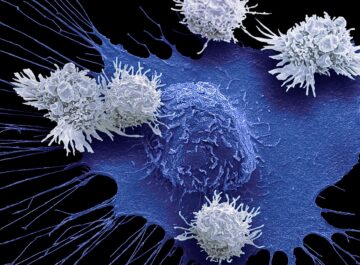

Because the likelihood of  US drug regulators dropped a bombshell in November 2023 when they announced an investigation into one of the most celebrated cancer treatments to emerge in decades. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said it was looking at whether a strategy that involves engineering a person’s immune cells to kill cancer was leading to new malignancies in people who had been treated with it.

US drug regulators dropped a bombshell in November 2023 when they announced an investigation into one of the most celebrated cancer treatments to emerge in decades. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said it was looking at whether a strategy that involves engineering a person’s immune cells to kill cancer was leading to new malignancies in people who had been treated with it.