by Thomas Fernandes

Part I can be seen here.

Being obligate scavengers, vultures are highly dependent on finding carrion, an unpredictable and patchy resource. This sometimes means going without food for two to three weeks while actively scouting 200 km per day. Unlike other animals that evolved strategies to enable them to secure food by hunting, vultures have evolved remarkable adaptations for energy conservation, enabling them to survive extended fasting periods.

Energy expenditure arises from three main sources: basal metabolism (organ function), thermoregulation, and activity such as flight. Vultures basal metabolic rate is already 40% lower than expected for birds of their size even if the mechanism behind it remains unclear. The second component, thermoregulation, can usually increase metabolic cost by ~15% under moderate conditions. However, vultures are exposed to extreme temperatures, from the intense desert heat on the ground to the very cold of high-altitude flight and desert night.

In other desert birds, when heat rises too much, they resort to panting to dissipate heat (as birds cannot sweat). This strategy is very energy intensive, increasing the metabolic rate drastically as the temperature rises, up to 150% in the most extreme case. In addition, this strategy uses water, again not ideal in deserts. If we approximate panting to the increased respiratory rate in flying pigeon it would cause an 8 fold increase in respiratory water loss which represented 30% of total water loss during flight.

Vultures instead rely on passive thermoregulation strategies, much like insulating a house reduces energy used in active air conditioning. Their measured thermal conductance is about 21% lower than expected for eagle relatives, which helps prevent rapid heating or cooling. However, in a living organism, this insulation also makes it harder to shed internal heat generated by exertion or prolonged exposure to high temperatures. To overcome this, they have evolved highly adaptable heat exchangers in their bare neck, head, and legs. All of these regions are highly vascularized with many superficial small veins sitting right under the skin, where they can shed heat efficiently into the environment, complemented by larger veins deeper in the tissues. From there, two pathways emerge.

One involves the majority of the returning blood flow to pass through the outside “scenic route” close to the skin and getting cooled. The outgoing blood in the arteries flows very close to these veins, sometimes with the veins partially enveloping the arteries, allowing heat to transfer from hot artery to cooling vein before reaching the surface. In short, a heat exchanger. The other path is when the blood returns mostly via the internal “highway veins” which reduce heat exchanges with the outside and with the arteries. The two paths are controlled by dilatation of blood vessels. Dilating the superficial small vessels orient more blood toward the skin, boosting heat dissipation; constricting them forces blood inward, conserving warmth.

Interestingly, little to no active control is needed as heat will in itself cause dilatation of the outside vessels, increasing blood flow through them and cold will constrict the outside vessels promoting the inside route.

Vulture behavior further exploit this mechanism for adaptable insulation levels. In hot weather, they stretch their head and neck outward and the bare skin darkens to a deep red as blood flow rises. This posture increases their total exposed skin to 32% of the surface. In the cold, the skin grows pale and wrinkled as the bird tucks its head, reducing the exposed area to only 7%. Such postural shifts can, under still air, nearly double the heat loss. This is the most probable reason behind the naked head of vulture.

As you know, after isolation, the second-best thing you can do limit your AC cost is to allow a slightly higher room temperature. This works for body temperature as well. Vultures tolerate wide core temperature fluctuations, up to 5 °C between dawn and midday. Instead of constantly countering the desert heat and night-time cold, they allow their bodies to accumulate heat steadily during the day and release it gradually at night. The energy stored this way, possibly every day, amounts to about one hour of metabolic demand.

If postural adjustments are insufficient, vultures employ another passive thermoregulation tool, urohydrosis (peeing on their legs). Because their legs are already highly effective heat exchangers, coating them in water greatly enhances cooling. Water thermal conduction is 25 times higher than air and the heat to evaporate the water can reduce their body temperature by about 2°C for a few minutes of urohydrosis.

If all else fails their most energy-efficient final measure is soaring at high altitude. If we consider a 1°C loss every 100m of altitude with vultures’ common flying altitude around 1000m, taking flight can easily reduce temperature by 10-15 °C.

This strategy is particularly effective because vultures are extremely efficient fliers. In complete contrast to insects, which must beat their wings hundreds of times per second (raising metabolic cost by 2,000% and body temperature by 15 °C) soaring vultures beat their wings only one to two times per minute, increasing their energy expense by barely 40%. This makes vultures among the most energy-efficient travelers of all animals. This efficiency comes mainly from vultures extremely large wingspans, which allows them to soar efficiently on thermals and cover vast distances while expending minimal energy.

The wide wings reduce wing loading and drag, enabling slow, gliding flight that maximizes energy savings. However, this design comes with a trade-off in their ability to pursue live prey. The longer wings are less maneuverable, making rapid turns or sudden bursts of speed more difficult. Albatrosses, the famous wingspan record holder, who also rely on scanning large oceanic areas for dispersed food, face a similar compromise and prioritized efficient travel over agile maneuvering.

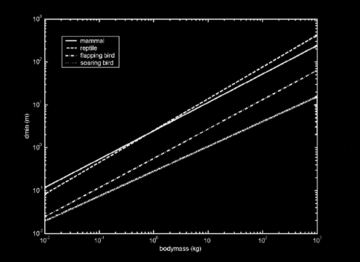

These adaptations illuminate why vultures are uniquely suited as scavengers. Supporting this, mathematical models estimated the minimal detection distances needed for different species to survive under a given food availability. The key principle is that a scavenger can only persist if its ability to locate food exceeds its energetic demands. Predictably, lowering energy costs is only part of the story; efficient travel and accurate food detection are equally crucial. In theory, some mammals could survive as obligate scavengers, but they face an additional challenge: locating food is not enough, they must reach it before competitors do. In this competition, vultures’ soaring efficiency gives them a decisive advantage, even with a minimal detection radius, these birds can subsist on smaller or more widely dispersed resources and flying only increases their detection range.

From their 1 km vantage points and with a visual accuracy superior to our own, they can spot even small carcasses, like 50 cm, from up to 2 km away. Beyond scanning the ground, they watch for other circling vultures; a single bird can alert others to a carcass tens of kilometers away, far beyond what it could detect alone. All those adaptations feed into the guild described in part one. The smaller gulpers that usually feed last on the remains would benefit more from attending other vultures’ clues than rippers looking to be the first to open the carcass.

This reliance on distant visual cues fits the wide, open habitats typical of Old-World vultures. But in more forested regions, where sight lines collapse and the ground is hidden under canopy, the situation changes. Here, some New World species, most famously the turkey vulture, appear to follow a different sensory path. Their olfactory bulb is unusually large for a bird, and they are very sensitive to specific decomposition volatiles produced within a day of death. Still, even with this sensitivity, smell behaves differently from sight: airborne compounds disperse rapidly and quantities become truly infinitesimal over long distances. This means that, unlike vision, olfaction does not scale well with altitude or offer broad detection radii. Precise olfactory detection distances for turkey vultures aren’t well quantified but behavioral evidence supports the notion that smell provides a reliable foraging cue over local scales. Under very dense vegetation where visual detection is limited, we could assume this developed sense of smell represents an increase in detection radius.

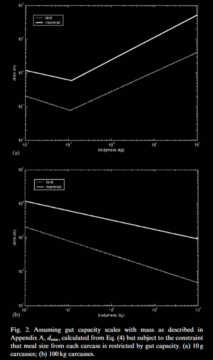

Figure 5 plots minimal detection efficiency against body size, suggesting that smaller scavengers would be more competitive because of lower energy demands. Even for soaring flyers where a larger mass confers advantages in soaring flight this doesn’t seem to offset the increased energy demands. Yet vultures are among the largest birds, which at first seems paradoxical. However, this only tells part of the story, because the model behind Figure 1 assumes food is distributed evenly in “very small packages”.

In reality, carrion is highly patchy, appearing unpredictably as scattered large units rather than uniform small meals. When models account for this patchiness, even as little as 10g carcasses shift equilibrium to 100g birds being favored as shown in Figure 6. As soon as we consider large animals like antelopes, the evolutionary pressure shifts toward larger scavengers: bigger individuals can consume more from a single carcass and store enough energy to wait for the next one.

This also explains the diversity of body sizes across vulture guilds and their dietary specializations. Rippers and gulpers can exploit an all‑you‑can‑eat buffet favoring larger size, whereas smaller “scrappers” feeding on the remains face more modest rewards of discovery and possibly mitigate some of the benefits of increased size.

Focusing specifically on this challenge of long fasting followed by rapid gorging proves insightful in explaining the acidic stomachs of vultures as well. Interestingly albatrosses not only share the wingspan of vulture but also have large and very acidic stomachs, despite not being primary carrion eaters. When they do find food, albatross can eat over 3 kg of food in one sitting which is more than 30% of their weight. This much food makes taking off difficult and considerably increases the energetic cost of flying until digestion is complete. A low stomach pH gives wandering albatrosses a strategic advantage since it allows them a rapid chemical breakdown of ingested food and therefore a rapid digestion. Like their bald heads, vultures’ acidic stomachs were once thought of mainly as defense against pathogens but seem better understood as a response to the twin pressures of a patchily distributed food supply and the energy-saving demands it imposes.

Bringing it all together, a simple model illustrates why scavenging is most efficient for birds capable of soaring flight. A ten-kilogram vulture feeding on a one-hundred-kilogram antelope carcass could survive with a minimal detection radius of only 150 meters, whereas a one-hundred-kilogram terrestrial carnivore, such as a hyena, would need to detect carcasses from a kilometer away to meet its energy demands. While the absolute numbers are somewhat arbitrary due to the simplicity of the model, the ratio highlights a key point: Scavenging is highly favored in birds that can travel long distances with minimal energy expenditure.

If soaring flight provides the functional advantage, efficient thermoregulation and acute sensory abilities all further reduce the energetic cost of locating and reaching carrion. Together, these pressures shaped vultures’ physiology and behavior to survive on scarce resources.

Finally, the long, broad wings that make vultures such efficient travelers come at the cost of maneuverability and the bursts of power needed for hunting. In short, obligate scavenging is rewarded. Terrestrial predators face no similar trade-offs, and thus there is little evolutionary pressure for them to abandon active hunting and specialize in obligate scavenging.

In this way, vultures occupy a singular ecological niche, shaped not by speed or aggression but by energy economy, patience, and extreme specialization.

Apologies for not responding to comments on my previous posts. A browser security setting was masking them without me noticing; this is now fixed.

Also I recently launched my substack: librotium. Animal behavior posts are for this 3QD series only but feel free to check out my attempts at understanding other things, starting with the name of my newsletter.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.