by Michael Liss

We had reached a place in Virginia. It was a very hot day. In this jungle, there was a man, a very tall man. He had with him his wife and several small children. We invited them over to have something to eat with us, and they refused. Then I brought something over to them on an old pie plate. They still refused. It was the husband who told me he didn’t care for anything to eat. But see, the baby was crying from hunger. —Jim Sheridan, Bonus Marcher, quoted in Studs Terkel’s Hard Times

There is a mood, a color, to the Great Depression. It’s a shade of gray, sooty and ominous, without sun, almost without hope. Wherever its victims stopped—on city streets and farms, on a muster line or on one for bread, outside tents or structures made of bits and pieces of packing boxes and cardboard, on trussed-up jalopies headed West, or on boxcars with hoboes like Jim Sheridan—there were chroniclers of images and words, all gray. Gray and ominous as well were the faces of those who were leaders in business and politics. Dark suits, white shirts, muted ties, emitting seriousness of purpose, and consciousness of class. Those men were Authorities—vested with power, but often remote from those who would be impacted by their actions, or non-action. They shared with their peers a fervent belief in their own self-worth, earned through moral superiority.

Herbert Hoover was in this second group. He had fought for and secured it through intensely hard work and great talent. He was the “Great Engineer,” the perfect man to be heir to a pro-business philosophy that had, in the Harding-Coolidge years, brought abundance. His landslide victory in November 1928 promised more of the same—more jobs, more innovation, more wealth, an appreciably raised standard of living, and the possibility of moving up in class, as he had. A better statesman for Capitalism, for the American Dream, for the American Promise was hard to imagine.

It blew up, of course, most spectacularly in the stock-market crash, but also as a result of secular forces both in the United States and abroad that made seemingly healthy economies reel. That these problems pre-dated Hoover’s taking office did not grant absolution for their existence. You don’t get a honeymoon in a crisis. Nor did successive governments in other Western countries get one. Democracy tottered because its stewards seemed inadequate to the task. Should they continue to prove to be inadequate, then more authoritarian forms of government might be the answer. Italy was already under the fist of Mussolini, Japan was eyeing China as a resource-filled morsel, and Germany was considering an angry man with a funny mustache who seemed a bit bellicose, but maybe could put people back to work.

What of the United States? In what direction would it go? In the first test of his leadership, Hoover did something surprising. He went away from his strengths. The Great Engineer, the man who could jump in and fix things, decided to play politics. He blamed Europe for everything. He played at the optics of leadership, hosting countless meetings designed to make him look like he was in command. And, finally, he made some policy decisions rooted in conventional orthodoxy, some understandable, others unequivocally bad.

In fairness, Hoover had a point in blaming Europe. Their chaos unquestionably became ours. There was the bizarre merry-go-round where Germany borrowed money (from American banks) to pay England and France WW-I Reparations, so England and France could repay American loans made during the War. There was England’s on-again, off-again relationship with the gold standard, destabilizing markets and causing a run on U.S. gold reserves, as foreigners, worried about devaluation, looked to repatriate hard currency. With every country fighting for market share, international cooperation collapsed. There were tariffs, the quintessential instrument of self-harming catnip, now a vehicle of retaliation. Mr. Hoover himself, on June 17, 1930, signed into law Smoot-Hawley, which led to levies on some 20,000 goods and converted trading partners into trading blood-rivals. Why did Hoover, presumably a man who believed in free markets, ignore the advice of so many from across the spectrum who warned about possible toxicity? The best answer we have is that he was swayed by other advice-givers who thought protectionism was a good sell in their states, and Hoover was looking at the midterms.

The net of this? Bad went to worse. In the first four months of 1931, the total value of world trade sank to just 42% of what it had been during the same period in 1929. Steel, always a target, always economically sensitive, was barely showing a pulse. The American steel industry worked at 12% of capacity in 1932. World commodity prices, especially agricultural ones, dropped by half and even more. It was becoming prohibitively expensive to grow anything, to dig up or otherwise extract anything, to manufacture anything, because prices wouldn’t support it. If you can’t grow or extract or make anything, how do you apply the capital you have and create more? If you can’t do that, how do you maintain employment? And if people are not employed, how do they consume and create demand for products? The nation looked to Hoover, and Hoover…looked off into the horizon, where a magical land of classical economics combined with a particularly American variant of self-absorption would cure everything.

This is how many Americans, and many historians, came to see Hoover, and it is not entirely fair. He did do some things. He supported the creation of the National Credit Corporation, with the intention of shoring up a weaker segment of the banking system. It largely failed because it called for investments from industry and finance, neither of which were eager to pony up. So, the U.S. Treasury would have to fund it, which it did through a new organization called the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. That did some good, but came with a peculiar, Hooverian twist. The big guys, the men who came to Hoover’s meetings and whom he saw as near peers, put their hands out first. Charles Gates Dawes—recently Calvin Coolidge’s Vice President, and the 1925 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize and first head of the RFC—threatened to close his bank (the Central Republic Bank and Trust Company of Chicago), unless he got $80M from the RFC. He got it. The Missouri Pacific Bank borrowed several million, used it to pay back a loan to J.P. Morgan, and then filed for bankruptcy.

For the big guys with the muscle, plenty of money. For the average, formerly working man, thoughts and prayers. Hoover wasn’t entirely blind to mounting unemployment, but only prepared to do his usual when it came to the jobless: rely on local, community-based volunteerism, in this case presumably supercharged with high-level leadership—because Hoover would appoint them. A new committee, the impressively named “President’s Organization On Unemployment Relief,” sprang into life, but, without public funding, it, too, was aspirational. Presumably, the unemployed would be inspired by the quality of the Board, which included, as chair, Walter Gifford, the head of ATT. Mr. Gifford was a particularly felicitous choice, as he subsequently testified at a 1932 Congressional hearing that he had no specific information regarding unemployment in the cities of Illinois, New York, and Pennsylvania, and did not believe there were any cold or hungry in those cities. Perhaps, a year and a half from the Crash, there hadn’t been adequate time to collect data.

Still, by the early part of 1932, some parts of Hoover’s approach seemed to be working, and a modest but perceptible recovery began to emerge. Hoover was heartened by this endorsement of his leadership and the expectation that the voter would recognize his excellence by supporting him for a second term. Unfortunately, this proved evanescent. Several Midwestern banks went under, production continued to fail, and unemployment, already at 8 million in 1931 rose to over 12 million in 1932. One out of four workers was out of a job. In fact, that was understating it, because roughly two million more were beyond counting, lost to rural/agricultural unemployment and the awfulness of foreclosures and eviction. Those folks were on the road, sleeping in the fields, in trucks, in railroad boxcars.

Inevitably, civil unrest had to emerge. The monied classes, inside and outside the government, comforted themselves with the thought that these “flare-ups” were the product of outside agitators—Communists, of course, Socialists, Anarchists, those who aimed at bringing down free markets. It never seemed to occur to many of them that conditions on the ground might have made for fertile fields for the opportunistic.

But those in need did understand it, and they didn’t need the Communists’ help to see it. In rural areas, they declared “Farmers Holidays” and withheld crops from the market. Others banded together to stop foreclosures—refusing to bid (or bidding pennies) for on-the-auction-block family farms, and, in some areas, physically reminding local judges of the wisdom of discretion in the application of law.

Industrial relations went south, generally. On April 1, 1932, 150,000 miners went out from the South Illinois coalfields. Violence ensued—some strike leaders mysteriously disappeared, some strike breakers the same. At one point, protesters/marchers were met by a force of 1,000 specially sworn in deputies. These men were armed with clubs and guns, including machine guns, with instructions to use them. Quite a number followed orders.

Not every movement was oppositional. In Seattle, an Unemployed Citizens League had success as a mutual reliance society, encouraging barter and the development of an alternate form of script. The idea went national, with organizations in more than 30 states trying similar programs.

What’s fascinating about these “coping attempts” is how closely the delivery of them matched Hoover’s ideas of localities providing for their own. Some of Terkel’s subjects talk about this as well—about the communitarian ideals of interdependence, of burden-sharing. The problem was scope. No matter how open-hearted a town might be, it lacked the resources to provide for everyone—and the greater the need, the less likely there was anything left to meet that need.

There had to be federal intervention. Only the federal government could marshal the resources, could borrow and spend, could organize on a national level. Many Conservatives in positions of authority at the state and local level knew this. They could see the suffering, and they could extrapolate from it the political risks to themselves and their party. They could also see the appeal of an alternate ideology (like fascism) if the present one proved unable to help.

Federal intervention, however, could only happen with a willing Congress and a willing President. Two years into Hoover’s Presidency, it was clear that both were absent. This framed, in the spring of 1932, one of the most interesting and impactful moments for the entire decade—the Bonus March.

‘

The Bonus March was all about a little piece of paper called an “Adjustment Compensation Certificate” that had been authorized and issued by Congress (over Coolidge’s veto) in 1924. Recognizing the difference in rates of pay for the boys who had gone “Over There” with the American Expeditionary Force and those who had stayed home, Congress created a program whereby WW-I veterans would be given additional compensation for a portion of the differential. For each day they were overseas, they earned an additional $1.25, and, for service in the United States, $1.00. The hitch to “The Bonus” was that it wasn’t payable until 1945.

Still, it was an asset, and for many vets who were destitute, a potential lifeline. A group of Portland-area servicemen, led by a laid-off cannery worker by the name of Walter W. Waters, decided that their Bonus Certificates were the only way out. They needed the maturity date accelerated. This was not entirely a new idea. In December 1931, a Texas Congressman, Wright Patman, who had also served in the AEF, introduced a bill to do just that, but Patman’s bill was bottled up in the Ways and Means Committee, essentially putting it into a state of suspended animation.

Of course, the immediate fate of the bill didn’t eliminate the issue, and, in mid-May, roughly 300 of Waters’ vets decided t head across the county to Washington to make their case. They marched, perhaps not as crisply as they had done more than a decade before, but they marched, and, when they hit East St. Louis, Illinois, they tried to commandeer a freight train on the old B&O line. They were met by Illinois National Guardsmen and (not particularly gently) loaded onto trucks aimed out of state, where they reconnected with train lines headed in the general direction of DC. From there, it was like a relay. Sometimes they were driven by local veterans’ groups that wanted to lend a hand, sometimes more brusquely, by state governments that didn’t want to deal with them and so transported them as quickly as possible.

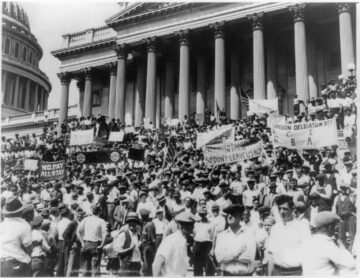

A real story was developing. The “Bonus March” caught the nation’s attention, and, not so gradually, its ranks began to increase. Each crossing added more men, some of whom brought along their families—and why not? There were no jobs to be had back home. By the time Waters and his advanced guard hit Washington, his vanguard of 300 had grown into perhaps 15,000. Soon, there would be roughly 60,000. They set up house in a few abandoned buildings ready for demolition, and, in the mud of the Anacostia River Flats, where they put up an entire town of shanties made of packing boxes, cardboard, and tarps.

Hoover, reading reports of their progress, was hostile. Hunger marches (and essentially that’s what the Bonus Army was, at least for a time) were something Washington had seen before, and Hoover had generally been neutral to supportive. For the veterans, he was not. He felt he’d already done things for them—and he had, including forming the Veterans Administration, and fighting for enhanced eligibility for disability pensions. He was not going to meet with them, and certainly not going to push for the type of legislation they wanted.

Strange loyalties ensued. The Bonus Army found a friend in Washington’s police chief, Pelham Glassford, who, for a time, had been the youngest United States Brigadier General in Europe and instantly empathized with them. He helped them lay out camps, arranged for fundraisers, and even testified before Congress. Congressman Patman rejected them. As did the American Legion. Some locals were impelled to help with food and cash, more didn’t like the mess and strain on city services. And the developers who wanted their abandoned buildings back for demolition began to pull strings to get a more forcible eviction process going.

One man had a change of heart—Hoover himself. Not on the actual issue of payment, but on basic needs. Privately, he authorized the distribution of cots, tents, field kitchens, and, after there were reports of illness, he ordered the army reserve to set up a field hospital.

Still, the marchers had come a very long way. They wanted a vote, and eventually they got one. No one in Congress really thought that the government had the money to pay out anywhere near what might have been earned at maturity. On June 15th, the Patman Bill came out of committee, and, by a narrow margin, the House adopted it, despite Hoover’s insistence that he would veto. Hope was permanently quashed when, two days later, the Senate overwhelmingly rejected it, 62-18.

They were done. There was no hope. By the hundreds, by the thousands, they drifted away, some using “borrowed money” from their Bonus Certificates (as authorized by Hoover and enacted by Congress) to get transport. But about 10,000 stayed, some stubborn, some hoping for a miracle, many with just no other place to go. Four weeks passed, and the stalemate continued.

It is what happened next that mattered and resonates even today. The owners of the 10 buildings scheduled for demolition were losing money, and pressed Glassford harder. On July 21st, he got a direct order to clear the buildings, by force, if necessary. He negotiated a private agreement to have the squatters move out of the buildings and relocated to other sites. On July 28th, a group of roughly 40 displaced members, led by an (actual) Communist, tried to retake one of the buildings. There, rocks and bricks were thrown, and Glassman himself was injured. At this, the District of Columbia’s Commissioners asked Hoover for federal troops.

Hoover balked, at first. Acutely aware of the optics of this, he demanded that the request be endorsed by Glassman personally. After a few hours, he got it. He then drafted precise orders to his Secretary of War, Patrick Hurley. Federal troops were not to be armed. Bonus Marchers were to be cleared from the downtown area and escorted to camps. Resisters would be arrested and turned over to the police. Hurley wanted more—for Hoover to declare a state of insurrection, but Hoover rejected it.

Hurley passed those orders on to the Army Chief of Staff, Major General Douglas MacArthur. The General ignored them. He ordered a mobilization in force, and dressed in his best peacock style. Fully be-medaled, he rode in on a white horse to take command. He wasn’t going to be satisfied with a small police action. He intended to clear the entire District of the marchers, to drive them out of their encampments, wherever they were located. He was accompanied by his aide, then-Major Dwight Eisenhower, who (may) have suggested MacArthur take a less prominent role. MacArthur had no intention of doing so.

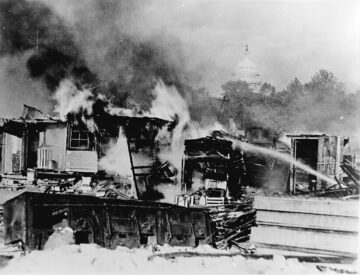

First, the squatters. The General’s men were superbly trained and outfitted, four troops of cavalry, bayonets fixed, a column of infantry, and five support tanks clanking behind them. After an exchange of rocks and tear gas, Major George S. Patton Jr. led what might have been the last horse cavalry charge down Pennsylvania Avenue. The tear gas, and Patton’s men’s sabers, were too much, and the Bonus Army men retreated to the Anacostia Flats. There, at the 11th Street Bridge, MacArthur reassembled his men, giving them first an hour for dinner and rest. During that time, he received another order (actually two) from Hoover not to cross the bridge.

This, he also ignored. MacArthur claimed to be certain that the “mob,” in his words, “was animated by the essence of revolution.” After an hour to give time for the women and children to be evacuated, his men resumed the advance. In the chaos, the entire settlement went up in flames. Patton, his blood up, personally torched the hut of Joseph T. Angelo, the man who had been decorated for saving Patton’s life during World War I. Questioned about it afterwards, Patton dismissed both the concerns, and the man.

MacArthur was exceptionally good at burnishing his own credentials, and that was true here. He held a news conference in which he took credit for ridding Washington of a dangerous element, while at the same time praising Hoover for acting decisively. That wrapped the two men together, locking Hoover into an unwanted embrace.

The public at large, as well as the media, was initially supportive, and the retreating Bonus Marchers were often faced with criticism and rejection. But, after a time, a different way of thinking began to take hold. The men, women, and children of the Bonus March were no mob, they were just ordinary people caught in a terrible present that was not their fault. The government’s claim that most of the Bonus Marchers were Communists and other radicals just didn’t ring true. Newsreels and newspaper photos showed that, and there was booing of the Army in movie houses. They seemed also to demonstrate something more—those gray, frightened, bedraggled people with absolutely nothing beyond a few tattered clothes could have been them. Even if there were some agitators in the crowd, that didn’t justify what many Americans thought of as a serious civic sin. Said Alabama Senator and future Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black:

As one citizen, I want to make my public protest against this militaristic way of handling a condition which has been brought about by widespread unemployment and hunger.

Hoover never quite got over it. He was angry with MacArthur for ignoring his orders, and angry with the press and public for failing to understand the need for firm leadership when, in his words,

the march was in considerable part organized and promoted by the Communists and included a large number of hoodlums and ex-convicts determined to raise a public disturbance.

As for his political opponents, he had nothing but anger. How awful of the Democrats, led by FDR, to try to capitalize on it. He carried those grievances for the rest of his public life. Twenty years later, he wrote this:

Probably the greatest coup of all was the distortion of the story of the Bonus March on Washington in July, 1932. About 11,000 supposed veterans congregated in Washington to urge action by Congress to pay a deferred war bonus in cash instead of over a period of years. The Democratic leaders did not organize the Bonus March nor conduct the ensuing riots. But the Democratic organization seized upon the incident with great avidity. Many Democratic speakers in the campaign of 1932 implied that I had murdered veterans on the streets of Washington.

Hoover had seen himself as savior, and, in doing so, forgot what he was supposed to save. As the ordinarily pro-Hoover Washington Daily News made clear:

If the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.