by Mark Harvey

The dark power at first held so high a place that it could wound all who were on the side of good and of the light. But in the end it perishes of its own darkness… —I Ching, #36, Ming

Years ago, someone gave me a copy of the I Ching, Book of Changes, translated by Richard Wilhelm. It’s a heavy little brick, more than 700 pages, and bound with a bright yellow cover. When I received the gift, I looked at it skeptically and never expected to read it. To my surprise, it’s been with me ever since, I’ve read it dozens of times, and the spine of the book is sadly broken from too many readings.

I grew up in a family with fairly skeptical parents and some very skeptical siblings. I vividly remember asking my parents if Santa Claus was real at an age when parents should definitely not disillusion a child of that belief. My parents looked at each other with pained expressions and then, too honest to lie about it, tried to let me down gently. So nothing in my formative years prepared me to like the I Ching.

Not all I Chings are equal, and there are some pretty flimsy versions out there. There’s even an app called I Ching Lite. Of the English versions, the Wilhelm/Baynes translation is one of the most respected.

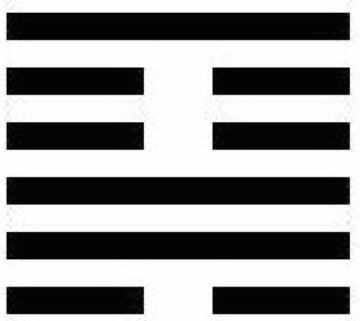

The I Ching is said to be almost 3,000 years old and originated in China’s Zhou Dynasty. The structure consists of six stacked lines (called hexagrams), each either broken or unbroken. You’ll remember from your high school math that if you have two binary options (broken or unbroken) on six lines, you end up with 64 possible combinations. And that’s what the I Ching looks like: 64 hexagrams, each with its own special meaning.

To read the I Ching properly, you’re supposed to use 50 yarrow stalks and a fairly complicated process of selection and elimination to arrive at any of the 64 hexagrams. You can also simplify the process by tossing three coins six times to arrive at the hexagrams. Being an impatient Westerner who drinks instant coffee and has almost no tolerance for drawn-out ceremony, I have never attempted the yarrow-stalk method. I used to do the coin method, but I have even abandoned that. Now I open the I Ching to a random page and read whatever hexagram I land on. Sometimes I’ll keep flipping pages until I arrive at a hexagram I like or that fits my mood.

My method is barbaric, artless, and shows a need for instant gratification. If I were born in China during the Shang Dynasty, I probably would have been punished severely for my uncouth readings, either with forced labor grinding grain or building walls.

It may be that the I Ching is based on divination and cleromancy (casting of lots). Still, the philosophy defined by the 64 hexagrams is sometimes far more helpful than any political theories in public life, which brings us to Donald Trump and the current state of America.

Even those who’ve read Sinclair Lewis, George Orwell, and Aldous Huxley, and have studied a bit of history, are struggling to understand what’s happening in our country right now. You can pick any of the vile acts of our government—snatching people off the street and deporting them with no due process, the extrajudicial killing of Venezuelans in fishing boats, alienating our most stalwart allies, a careless foreign policy—and try to interpret them through the lens of political science. But our usual means of interpreting these trends seem to fall short these days. The I Ching, with its thousands of years of history and practice, might help.

Americans tend to take the short view in business and politics, breaking things into quarters, midterms, and at longest, five-year plans. And our view of the world is almost mechanical: If the economy is faltering, cut interest rates; if the vote swings to the left, remap districts; if heart disease is killing in the millions, find the proper medication. The philosophy from the I Ching takes a broader view of the universe, the patterns of nature, and the inevitability of change, and offers ways to face these patterns.

If you’re a sinologist, give me a little leeway here with my interpretations. My knowledge of China, admittedly, could fit into a fortune cookie with extra room for a Peking Duck.

There are various hexagrams that could describe America today and some hexagrams that might offer a path out. If I understand the I Ching correctly, Donald Trump didn’t come to power and get us to our rotten state on his own. Rather, a fundamental decay in our principles and society, plus a dash of cosmic patterns, created the perfect environment for the Orange House of Spray Tan to ascend.

Some hexagrams come in pairs and are the exact inverse of each other. For instance, hexagram #17, Sui (Following), is the inverse of hexagram #18, Ku (Work on what has been spoiled). Take Sui and turn it upside down, and you get Ku. And philosophically, the two work together.

The fourth line of Sui is solid and, as translated in the Wilhelm edition, perfectly describes Trump and his lackeys. It reads,

It often happens, when a man exerts a certain amount of influence, that he obtains a following by condescension toward inferiors. But the people who attach themselves to him are not honest in their intentions. They seek personal advantage and try to make themselves indispensable through flattery and subservience.

I think we always knew this country had its share of sycophants, but the sheer number of self-proclaimed Christians, business leaders, and cabinet members willing to prostrate themselves before the President suggests we’re in a period of utter rot.

There are various hexagrams that describe the quality of today’s American iniquity. The first line of Number 44—again using the Wilhelm edition—says,

If an inferior element has wormed its way in, it must be energetically checked at once. By consistently checking it, bad effects can be avoided. If it is allowed to take its course, misfortune is bound to result; the insignificance of that which creeps in should not be a temptation to underrate it. A pig that is still young and lean cannot rage around much, but after it has eaten its fill and become strong, its true nature comes out if it has not previously been curbed.

President Trump could never be described as “young and lean,” but since we didn’t check his smaller power as a weanling during his first term, we are now facing something truly piggish in his second term.

The I Ching was written during the reign of an evil and inferior ruler, Di Xin, during the Shang Dynasty. Di Xin was said to hold elaborate orgies, and one of his most notorious was called the Lake of Wine and Forest of Meat, in which a pool large enough to hold canoes was filled with wine, and a “forest” made of meat skewers resembling trees was constructed. His guests could float in the lake and reach down with cupped hands for wine, and pick meat off the trees as they floated past. The King was also said to take near sexual pleasure in torturing his enemies.

I guess we’re not at the wine lake/meat forest era yet, but all the gilding of the WhiteHouse, the tearing down of the East Wing to construct a massive ballroom, and the Gatsby themed party earlier this fall sure smack of the same debauchery. And when it comes to taking pleasure in the suffering of others, one can’t help but think of Kristi Noem and Stephen Miller.

Just as the I Ching warns of how the inferior man insinuates himself into power, the text advises us on ways out. Hexagram 18, Ku, is represented by a Chinese character that symbolizes a bowl of breeding worms. The judgment of Ku reads,

What has been spoiled through man’s fault can be made good again through man’s work. It is not immutable fate, as in the time of standstill, that has caused the state of corruption, but rather the abuse of human freedom. Work toward improving conditions promises well, because it accords the possibilities of the time. We must not recoil from work and danger-symbolized by crossing of the great water-but must take hold energetically.

The Shang Dynasty ended in 1046 BC, and its ending is credited to a man named Ji Chang, elevated to the title of King posthumously. Ji Chang was the vassal ruler of the Zhou province of western China and he didn’t directly overthrow the evil King. But it’s said that he ruled with restraint, mercy, and most of all with virtue. He also formed alliances with other disaffected states, paving the way for his son Ji Fa to become King.

Ji Chang’s example of temperance and morality was the framework for China’s political philosophy for more than 2,000 years: the Mandate of Heaven. In simple terms, the philosophy says that Heaven grants rulers a mandate if they are just, virtuous, protect the weak, and wisely care for their people. The corollary is that Heaven will remove the privilege of office if the ruler is tyrannical and corrupt.

Even with my thin knowledge of Chinese philosophy, I can say with certainty that we are not being ruled by a president who has the Mandate of Heaven. Our President is what the Chinese so often call an inferior man—corrupt, cruel, and capricious. The inferior man avoids responsibility, blames others, and exploits chaos. If we’re to remedy our situation and reclaim the Mandate of Heaven, the I Ching is rich with hexagrams that offer sound advice.

It is a cause for optimism in that it emphatically and repeatedly says what has been spoiled can be made good again through hard work, hewing to our best values, and time. We can begin what will be a long path in America toward redemption by elevating leaders of character and competence, not those who are so obviously unsuited to lead.