by Steve Szilagyi

Prologue

Most people visit the James A. Garfield Memorial to admire its Victorian splendor, or to pay respects to a forgotten president. I go for another reason: my great-great-grandfather carved some of its stone. If Garfield had lived out his term, the man might never have come to Cleveland, never met the woman who became my great-great-grandmother, and I—and a whole thicket of brothers, sisters, cousins, and aunts—would never have arrived on this earth. Absurd as it sounds, my existence is one more ripple in the long aftermath of a presidential assassination. Before getting to that family tale, it’s worth recalling who Garfield was, and why his loss mattered far beyond my own accidental genealogy.

James A. Garfield was the most qualified man ever to be elected president of the United States. He was a fine physical specimen: six foot, 185 pounds, born in a log cabin, and good with his fists. He had a towering intellect, led a frontier college, taught the classics, and could write in Latin with one hand, Greek with the other. People liked him, even his political enemies. He’d greet you with a bear hug on his way to the lectern or pulpit to deliver a thoughtful speech or sermon (he was an ordained minister in the Disciples of Christ church). A fervent abolitionist and Civil War hero, he served nine terms in Congress and knew how to work the levers of government.

Most attractively, when he was nominated for the presidency as a compromise candidate in a deadlocked 1880 Republican convention, he didn’t want the job. Seriously. His long seniority in the House gave him power and influence he was reluctant to sacrifice.

But once this superb human being, this fine farmer, husband, and father of five surviving children, moved into the White House in 1881, he never got the chance to fulfill his promise or address the great issues of his day—reconstruction, national infrastructure, justice for Native Americans—or set a moral direction for America’s growing wealth and international presence. Instead, he spent almost every minute of his scant 120 days in office wrestling with the squalid business of political patronage—battling the corrupt rascals of his own party who were desperate to preserve their petty prerogatives in the distribution of remunerative public offices.

He had only just scored a solid victory in this effort, humiliating his chief enemy, the villainous Senator Roscoe Conkling, and was eagerly preparing to take on the real work of the presidency when he was shot in the back by a perfect fool, and killed—after two agonizing months—by inept doctors who probed his wound with dirty fingers.

Six months as president. That was all he got.

Garfield’s story is ably told in two splendid recent biographies: President Garfield: From Radical to Unifier by C. W. Goodyear (2023), and the gripping Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President by Candice Millard (2011). Goodyear’s book is essential for understanding why Garfield mattered to the people and the politics of his time, and Millard’s is a ripping yarn, and undoubtedly the inspiration for Death by Lightning (2025), a Netflix limited series dramatizing the parallel stories of Garfield and his assassin.

He was unquestionably the good guy. The negative charge most often laid against Garfield was that he was too much of a compromiser. He tried to see both sides of an issue and was too often in favor of negotiation when his associates preferred to make a show of hanging tough.

His enemies, on the other hand, were as rascally a set of scoundrels as ever plundered the public purse. They included the aforementioned Conkling of New York, the former President Ulysses S. Grant, and various wingmen in the Republican machine—men whose petty wars over patronage overshadowed the real work the nation needed done.

After he was wounded, Garfield lay dying for two months. Every up and down of his condition during that time was headline news in the gaudy popular press. These accounts built up so much public steam that when Garfield finally breathed his last, there was an explosion of popular grief of a depth not seen since the death of Lincoln.

“His death appeared to me as among the gloomiest calamities that could have come to my people,” – Frederick Douglass

Garfield was born, lived in, and served as congressman for Northeast Ohio. So it was in the City of Cleveland that a subscription was quickly launched to build a permanent monument for the fallen president. More than 110,000 private citizens contributed, with hundreds schoolchildren donating their proverbial pennies. A site was chosen at the top of a magnificent hill in Cleveland’s Lakeview Cemetery—today a virtual arboretum, with spiky obelisks and grand mausoleums overlooking the city.

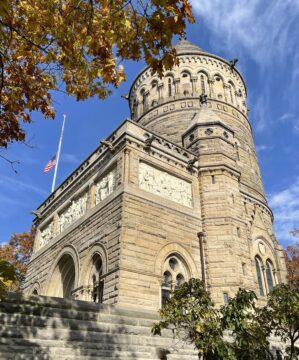

A design for the combination tomb and memorial was launched and won by Connecticut architect George Keller. He designed a circular tower with a conical roof to house a 12-foot statue of the late president, rising from atop a drum-shaped tomb chamber, where Garfield’s body, and later that of his wife, would lie in a freestanding marble sarcophagus.

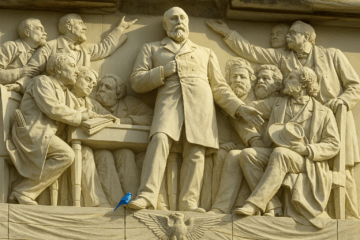

The Memorial is heavy, Romanesque in its arches and doorways, and constructed of blocks of worked granite. It is reached by broad steps and has a high portico with a fine view of downtown Cleveland, Case Western Reserve University, and Lake Erie. Around the portico are four terra-cotta bas-relief panels containing more than 100 life-sized figures illustrating episodes from Garfield’s life. The high, circular rotunda inside is spectacular, with stained glass windows, columns, chandeliers—the works, wonderfully executed with the fine materials by accomplished craftspeople from around the world. The centerpiece is a 12-foot-tall marble statue of the late president, standing under a halo of lights.

And it is there, in the stonework of the Garfield Memorial, that my mother’s family—and therefore I myself—enter the story. This building, raised in grief over a fallen president, is the historical hinge upon which my mother’s family swung into existence.

It goes like this. I had a great-great grandfather. His first and middle names were Johan Nikolas. He was born in Bavaria in 1842 and learned the trade of stone carving. He came to the United States around 1870, to heavily German Cincinnati, Ohio, where he applied his skills to what was to become the sculpted jewel of that city’s downtown: Fountain Square. While working on the fountain, he got an official letter from Bavaria. It was his draft notice. Bavaria’s army was joining the Franco-Prussian war, and young Johan Nikolas wisely decided to keep out of it and remain in the States.

About a decade later, he got wind of a gig up in Cleveland. They were building a colossal granite memorial to the recently slain president Garfield, and men who could swing a hammer and chisel were in big demand. Johan Nikolas packed up his tools, and made his way up to Cleveland, where he joined the crews elaborating the exterior of the great edifice.

While in Cleveland, he met and wed his future wife, Margaretha. And once the Garfield Memorial was complete, he settled in downtown, opened and stone-carving shop outside another cemetery, and lived out his days. (Some of his stone angels are still to be seen poking up behind the walls of Cleveland’s older cemeteries.)

So goes the family legend.

Of course, there are an infinite number of colliding atoms in the chain of causality leading to any event. But such is the human thirst for distinction, that I take pride in the fact that my existence is associated with an event of national historical importance – even one so hideous and shameful as a presidential assassination. And not only my existence, of course, but that of my brothers, sisters, uncles, cousins and aunts. None of us would be here if Garfield had not died as he did, and Johan Nikolas had not come to Cleveland to work on the tomb and meet his future life.

Many years ago, I was introduced to a fine-looking gentleman I’d been told was the great-grandson of President Garfield. It was at a high society charity event, and I was already feeling underdressed and out of my element. Shaking hands with this direct lineal descendent of a man who’d shaken the hand of Abraham Lincoln, I could think of nothing to say but, “Do you know, if your great grandfather hadn’t been shot, I would never have been born?”

In return for this remark, I got that “Who let this idiot in?” look I know so well, and I went on to sputter out the rest of my tale, which seemed to interest him not in the least (though his wife gave an appreciative chuckle).

I was, perhaps, primed to ponder path dependency, as a child, by my mother. When we were all little. She’d pause from her household chores and curl up on our ratty old couch, and every kid at hand would jump up and snuggle around her, while she entertained us with stories and funny voices. One day, she was frowning into the middle distance. We asked her what was wrong.

“I was just thinking,” she said. “What would have happened if I’d never met your father. Where would you all be? Would you still be where you were before you were born? Or would you be born as someone else? With different parents?”

Pretty heavy stuff to lay on a bunch of 3 to-9-year-olds. Much like pondering who or where I would be if Garfield had been wearing a bullet-proof vest the day he was shot.

Certainly American politics would have been different. After Garfield’s death, the Republican Party drifted without enthusiasm for his successor, allowing the Democrats to recapture the presidency for the first time since the Civil War and setting in motion a string of destabilizing events that left the nation seesawing between factions for decades. It isn’t hard to sketch out the alternate timeline: a strong, stable, two-term Garfield presidency dampens the patronage wars, steadies the party, and likely averts the Taft–Roosevelt split that handed the White House to Woodrow Wilson. And if Wilson isn’t president in 1914, the entire character of World War One—and the century that followed—changes. No Bolshevik coup in a collapsing Russia, no Versailles humiliation ripe for a demagogue, no Hitler, no Holocaust, no Maoist catastrophes, no Cold War, no Middle East shaped by imperial debris.

It should be pretty clear that tens of millions of lives might have unfolded differently if Garfield had simply been allowed to finish the work he’d barely begun. The world would unquestionably be a better place. On the other hand, I would never have been born. So the heck with that.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.