by Malcolm Murray

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

“Humans are lucky to have Yudkowsky and Soares in our corner, reminding us not to waste the brief window that we have to make decisions about our future.”— Grimes

Probably the first book with blurbs from both Ben Bernanke and Grimes, a breadth befitting of the book’s topic – existential risk (x-risk) from AI, which is a concern for all of humanity, whether you are an economist or an artist. As is clear from its in-your-face title, with If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies (IABIED), Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares have set out to write the AI x-risk (AIXR) book to end all AIXR books. In that, they have largely succeeded. It is well-structured and legible; concise, yet comprehensive (given Yudkowsky’s typically more scientific writing, his co-author Soares must have done a tremendous job!) It breezily but thoroughly progresses through the why, the how and the what of the AIXR argument. It is the best and most airtight outline of the argument that artificial superintelligence (ASI) could portend the end of humanity.

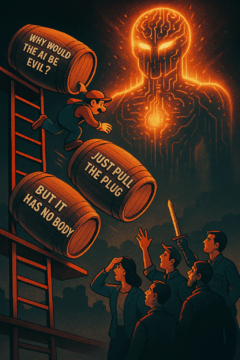

Although its roots can be traced back millennia as a fear of the other, of Homo sapiens being superseded by a superior the way we superseded the Neanderthals, the current form of this argument is younger. I.J. Good posited in 1965 that artificial general intelligence (AGI) would be the last invention we would need to make and in the decades after, thinkers realized that it might in fact also be the last invention we would make in any case, since we would not be around to make any more. Yudkowsky himself has been one of the most prominent and earliest thinkers behind this argument, writing about the dangers of artificial intelligence from the early 2000s. He is therefore perfectly placed to deliver this book. He has heard every question, every counterargument, a thousand times (“Why would the AI be evil?”, “Why don’t we just pull the plug?”, etc.) This book closes all those potential loopholes and delivers the strong version of the argument. If ASI is built, it very plausibly leads to human extinction. End of story. No buts. So far, so good. As a book, it is very strong. Personally, I could live without the scenario it includes in the middle of the book – I always feel writing out scenarios opens up more holes than it closes (and why is it always biological weapons? I would hope an actual ASI could think of more interesting ways to kill off humans), but it is the norm for this kind of book and can sometimes be helpful.

However, with a book like this, with a specific argument that it is selling, that clearly is written to achieve a goal, the other question we have to ask ourselves, is the why of the book. What is its purpose and what is it trying to achieve? Here I am much less positive. It seems to me that in order to have impact, a book needs to pass through three filters. It needs to reach the right audience, it needs to convince that audience of its message, and it needs to have a clear path of action for that audience to take based on the message. I worry that this book falls short in all three.

First, will it reach the right audience? The AIXR argument is currently facing headwinds, as far as public awareness and interest go. The AIXR debate goes through cycles, similar to AI development itself, with “AI summers” followed by “AI winters”. The arrival of Bostrom’s book Superintelligence in 2014 led to an AIXR summer, as did the arrival of ChatGPT in 2022. However, between those, like now, we are in more of an AIXR winter. What could thaw the AIXR winter would be either that a select group of the right decisionmakers, in government and business, became convinced of the argument and the necessity to act on it, or that we see a large public interest and concern for the question. When prompted, in surveys, the public does express a concern about AI. However, when unprompted, and simply asked for top issues, AI does not make the list of key concerns for the average voter. I do not think this book will be read by a broad enough swath of the public to change that. As for decisionmakers, the business leaders in AI are all deeply familiar with this argument already and have rejected it (you cannot convince someone whose paycheck depends on not understanding it, as per Sinclair), and politicians who have never heard of the argument are unlikely to pick up this book.

But let us be generous and say the book’s message is in fact consumed by a few newbies to the argument and go to bottleneck #2 – will it convince them? As mentioned above, this is the most airtight expression of this argument. However, the reason people reject the argument is not on account of the strength of its logic, it is all emotional. People in general do not like to think about extinction, or even risk in general. They would rather posit all kinds of emotional counterarguments. Yudkowsky and Soares work hard in the book to jump over all of the emotional arguments and cognitive showstoppers people throw at them. From the classic “Doesn’t AI need to be conscious to have wants?” to newer, more nuanced arguments such as “But AI doesn’t have a body, how would it kill us?” But like Mario dodging barrels in Donkey Kong, it is a never-ending quest. For every argument they gracefully leap over, new ones come at them. If people do not want to believe, they will not believe. Like this recent paper quoting the movie Don’t look up, “I say we sit tight and assess”.

Finally, even for those few newbies who do pick up the book and who do get convinced of the argument, can and will they take any relevant action as a result? As the book itself states, it is actually only a few groups – they mention politicians, policy wonks or journalists – that can take any action. For the rest of us, the authors quote C.S. Lewis, saying that we should not cower down, but continue to live a life that is as meaningful as possible. We should bathe our kids and chat to our friends. This is all well and true, but we knew that already. A million other books, from Epictetus to Burkeman, have told us this already. So, I am skeptical to the amount of impact that this book will have, despite its elegant execution.

However, as Scott Alexander wrote in his review of What We Owe The Future, the point of a book is of course not just the book itself, it is also that it provides a platform. What IABIED achieves is that it puts an unavoidable stake in the ground. It creates a platform from which other AI thinkers can shout their message. It provides us with a magic sword that we can wield whenever anyone tries to raise the simplistic counterarguments (“Duh, why don’t we just pull the plug?”) It can lift the debate to second- and third-order effects. We can start thinking about what it would take to prevent ASI even as the march toward AGI seems locked in. We can start looking at what indicators we would have that ASI is approaching. And that is indeed something. Paraphrasing Jane Hirshfield, IABIED ensures that they cannot say we didn’t know. We knew. It burned. We warmed ourselves by it, read by its light, praised, and it burned, with the energy of a million NVIDIA chips.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.