Elie Dolgin in Science:

Mischel’s first curious observation had to do with how quickly glioblastomas adapted to treatment. Within a week or two, tumors that had once bristled with extra copies of the receptor gene, EGFR, shed most of them. That kind of genomic shift should have unfolded gradually, over successive rounds of cell division. Instead, it happened with unsettling speed. Stranger still, cells that had seemingly rid themselves of EGFR retained the uncanny ability to bring it roaring back, spawning new tumors with high gene expression as soon as the drug pressure lifted. It was like watching a doused fire suddenly reignite from cold ash.

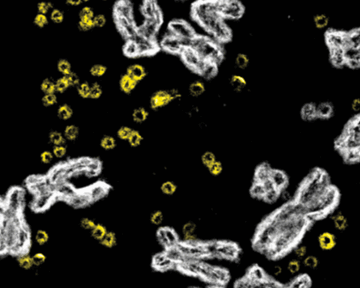

“The tumors were changing their genomes way too quickly,” says Mischel, a neuropathologist and cancer biologist now at Stanford Medicine. “It was a colossal scratching of heads.” The mystery deepened when David Nathanson, a trainee in Mischel’s lab, began to examine glioblastoma cells under the microscope. He stained chromosomes blue; EGFR was tagged in red. He expected the red signals—the extra copies of EGFR—to align neatly along the blue chromosomes. What appeared instead was chaos: scattered red dots drifting across the nucleus, unmoored from any chromosomal structure. “It was really crazy to see,” says Nathanson, now a brain cancer biologist at the University of California (UC), Los Angeles.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.