by Scott Samuelson

Though I can’t say that I’ve made any great effort to learn how to meditate or be mindful, the experiences I’ve had have left me cold. Not only am I no good at emptying my mind, I don’t want to empty my mind. I enjoy thinking. Plus, the only times I’ve been anything like “mindful” have been precisely the times when I wasn’t at all focused on being mindful.

While an enviously calm slow breathy voice is intoning, “Breathe in . . . breathe out . . . focus on each breath . . . let go of your thoughts,” I’m thinking, “Can I consciously let go of consciousness? Wait, I’m thinking about not thinking—stop that. Now I’m thinking about thinking about not thinking. Why am I trying to let go of my thoughts, anyway? Isn’t not-thinking what evil people want you to do? Also, I’m beginning to feel light-headed.” It doesn’t help that I’ve hated sitting cross-legged on the floor ever since kindergarten.

Still, I like the idea of a meditative practice that makes use of the one thing that we’re always doing—unless we’re underwater or dead. Like anyone, I can go down bad mental rabbit holes and am prone to all the clingy egocentrism that spiritual traditions rail against. I could use a calming mental discipline—so long as it doesn’t involve trying to space out with my fingers in a weird formation.

So, I decided to come up with my own breathing meditation. After a few months of trying it out, I’m pleased to say that it works marvelously and avoids the pitfalls of my previous experiences.

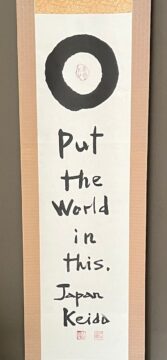

Friends inform me that it’s actually a form of Zen meditation. That makes sense, because all the good original ideas I’ve ever had turn out to be unoriginal. Also, whenever I’ve read Zen poets or philosophers, or wandered in actual Zen gardens, I’ve felt like I was in the presence of something usefully useless.

Zen or not Zen, my breathing meditation is very simple. Breathe in and think about a word. Then breathe out and think about a related word. Then keep breathing in and out, letting your mind wander on those words as long as you want. Then do it again with a different set of words. As for the technique of breathing, do it however you like to breathe—through the nose, through the mouth, standing, sitting, lying down, eyes open, eyes closed, whatever. Look, you’ve got it down already!

For instance, I breathe in and think of the word “life,” then breathe out and think of the word “death.” Life. Death. Life. Death. Then I think whatever I want to on that theme. Breathe in: “I need air to be alive.” Breathe out: “Someday my last breath will be exhaled.” Breathe in: “Even if I try to hold onto breath, I can do it only so long, then death comes.” Breathe out: “Likewise, I can’t rest in death too long before I need to take in life.”

After a while, I might reverse it, breathing in “death” and breathing out “life.” Maybe now I’m thinking about how things have to die to sustain me, and what I exhale or excrete is sustaining to the ecology around me. Or maybe I start thinking about loved ones who have died and become part of me. Whatever I’m thinking, it’s conditioned by the rhythm of in-out. Sometimes I even get to the point where I’m just thinking “life-death, life-death, life-death” for several breaths, and it seems to encompass everything. Mindful mindlessness, sort of. Totally by accident.

As soon as I’ve exhausted the life-death track, I come up with a new pair of words. Or else I quit and get on with my life—or maybe I should say my life-death.

Though opposite pairs work well (open-close, hello-goodbye, peace-war), the words don’t have to be opposites. Sometimes a pair that’s related in other ways can be illuminating: love-grief, walk-run, blue-green. Sometimes even a random pair can be great, though sometimes random pairs don’t go anywhere, which is also fine. (One of the things I insist on in my breathing meditation is that whatever I’m thinking or not thinking is perfectly fine. I’m doing this only because I want to. It’s not about conforming to some external standard. There’s no getting offtrack when there’s no track to begin with!)

There are several upshots of my practice. I find it refreshing. I generally enjoy the trains of thought and the turns they take. Though it never solves all my problems, it tends to soften them. It sometimes gives me good ideas. It sometimes even centers me to do something worthwhile. I can do it as little or as long as I want. I can also do it anywhere. For instance, while waiting for my coffee to brew, I might breathe in “cup of coffee” and breathe out “dried-up roast goat.”*

My breathing meditation also drives home some big lessons.

First, it’s not all about me. In fact, it’s almost exclusively about not-me. Even being me is mostly about not-me! I’m dependent to my core. I’m constantly having to take in the not-me and let go of the not-me. And not-me is doing most of the work. Like some magical team of elves, my body harvests the air, works it over, cooks it up, feeds it to my cells, and then hauls out the waste. Again and again and again. It’s astonishing. The world might temporarily need me to be breathing in and out, but my team of elves definitely needs the generosity of the world as long as I’m around.

Second, control is mostly an illusion. I have minor control over my breathing, but at some point inhale becomes exhale becomes inhale, whether I want it to or not. Likewise, though I can prompt my mind with various words, my thoughts follow their own paths, run out of steam, and need restarting. Come to think of it, the fact that thinking rides atop all these breaths is astonishing and beautiful.

Third, I must die. There will come a time when a last breath leaves my lungs. But not now. Now I’m alive. Damn lucky.

There’s one more thing that my breathing exercise suggests to me. What is breath? Originally, that’s a religious question. It’s spirit. Ruach. Spiritus. It’s the source of life itself. It’s the rhythm at the root of all our rhythms. It makes things appear and disappear. It makes me appear and disappear. The fundamental metaphysical question isn’t so much “Why is there being rather than nothing?” as “Why is there being and nothing rather than nothing and nothing or being and being?” Before this rhythmic mystery all my blue-green thoughts must bow down.

That said, if you decide to try out my breathing meditation, you shouldn’t worry about backing into any big ideas about the cosmos. I’ve found that it works best when you just let your mind wander and don’t worry about where it’s going. I’ve probably said too much already.

***

*A reference to the libretto of Bach’s Coffee Cantata: “If I wasn’t allowed to drink a cup of coffee three times a day, in anguish I would turn into dried-up roast goat.”

***

Scott Samuelson holds a joint appointment at Iowa State University in Philosophy & Religious Studies and Extension & Outreach. He’s the author of three books: Rome as a Guide to the Good Life, Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering, and The Deepest Human Life—all published by the University of Chicago Press. His forthcoming book is The Angels of Bread: Lessons in Making Food and Being Human.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.