by Thomas Fernandes

In part I we’ve seen how bees fly and generate astonishing metabolic energy just to remain airborne. But what do they do with that flight? As exemplified by nectar foraging, taking advantage of flight also means developing the perceptual and cognitive tools necessary to navigate the world. So far this was a solitary bee’s world but the particularities of honeybee lie in their social organization. Let’s look inside the hive.

Compared to solitary bees, in social bees the hive exists only to propagate the queen’s genes. Workers are sterile and their bodies, shaped by evolution, serve only the collective. Under such selective pressure the initial ovipositor, the egg laying appendage, of worker bees is modified into a barbed, irreversible stinger. In defending the hive, she dies. Only in eusocial species like honeybees does evolution favor such sacrifice for the group. Each worker follows a precise schedule from birth: 12 days of brood care, then wax production for honeycomb construction, then foraging until death, worn out by relentless flying.

This social structure allows for efficient food processing. When a nectar foraging bee returns, the nectar is unloaded to an awaiting younger worker bee and the honey making can start. The nectar is passed mouth to mouth, its sugars broken down by enzymes, then fanned with wings until it thickens into honey. A well calibrated practice that produces a substance which never rots due to its low water content, too tightly bound to sugar to be used by bacteria. This honey storage is how the hive survives winter as a colony, unlike social wasps where only the queen hibernates through winter while the rest of the colony die. It takes 30 kg of honey for a hive to pass winter, each kilo the result of a combined foraging effort amounting to four trips around the globe.

The other food source of bees, pollen, is used to make “bee bread” that will also be stored in combs. Mostly pollen serves to feed the larvae and young bee but cannot be digested raw. Instead, bees will make bee bread by fermenting pollen with honey and saliva creating a digestible protein-rich food that stores through winter.

Yet with 60 000 members and nectar returns that can vary by two orders of magnitude from one day to the next a rigid organization cannot function. Coordination requires adaptability and communication. Bees will communicate information through dances. One such dance is the tremble dance used to coordinate work inside the hive. If there are not enough workers to unload the nectar, a foraging bee will produce a tremble dance, a specific kind of piping. Seeley et al. describe piping as a “rapid contractions of the thoracic muscles, transmitted by the bee pressing her thorax onto her substrate, and consist of single pulses of sound lasting from 0.2 s to about 2.0 s”. There are different kinds of piping for communication. This brief, constant-frequency one signals to the hive that they should shift focus toward receiving nectar.

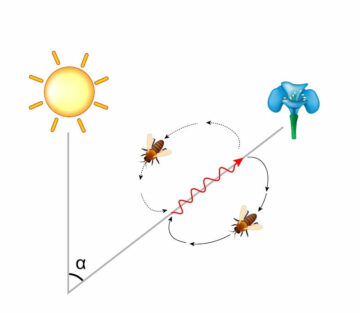

The tremble dance coordinates internal workflow, but bees also share information about the outside world through the more famous waggle dance. Foraging bees do not only carry back nectar or pollen but information about the most profitable patches and communicate it through the waggle dance. The waggle dance is a figure-eight movement performed by honeybees to communicate the location of profitable food sources. The direction of the waggle run indicates the angle to the food relative to the sun, while the duration indicates the distance and the intensity of the waggle conveys the quality of the source.

To understand how bees interpret these dances, we need to briefly step into their perceptual world. Their vision is shifted into the ultraviolet, and they sense light polarization as clearly as we see color. Sunlight scatters in the atmosphere, creating polarization patterns that their brains read instantly to locate the sun, much as a player reads a ball’s trajectory without calculating equations. But unlike the player, bees don’t need to watch the ball; the direction is encoded in every ray of light. Although it might appear to us as though we have decoded an elaborate signal the wonder is not in the coding. In fact, a better analogy is miming. No words are spoken, yet the direction is clear. The waggle dance of the honeybee is a bodily gesture that points, not with hands, but with movement. What she’s miming is a journey: the angle to the sun, the distance to the flower, the richness of the reward. And because other bees see in polarized light and think in foraging opportunities, they read this mime as effortlessly as we read a gesture. To our eyes, this first appears like meaningless movement, the sense of which is only revealed after examination and understanding of their world view. This is the richness of seeing diversity: new ways of seeing we cannot directly experience. It opens questions we wouldn’t otherwise ask. It explains the world differently.

Sharing information enables coordination, but also collective decision making.

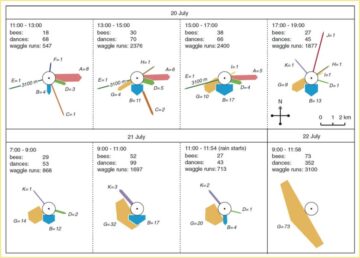

When a swarm looks for a hive the most experienced foragers will act as scout for the swarm. Scouts seek sealed cavity of volume greater than 10 liters with a small opening located at the floor of the cavity, itself at least 5 m above the ground and facing south. Remarkably, no single bee surveys all options yet; in an emerging process the swarm will go from multiple possible sites to all dancing for the same site in a few days. The result is astonishing but the process is quite simple. Each scout reports faithfully their finding by waggle dancing for a potential site. After their initial report they show decaying interest (in the form of reduced dancing time), relying on other scouts to enhance the signal if they agree after exploration. A hive mind made all the more surprising that all individual bees exhibit individual cognition and decision-making during foraging and throughout this process. This form of consensus has inspired neuroscientists looking for analogs in how the brain is able to generate decentralized decision making. Their theory goes like this: Different groups of neurons, each encoding a potential action or interpretation, accumulate evidence over time. Through selective reinforcement of the strongest option, the brain, like the swarm, can reach a consensus. There is no single command neuron, just as there is no bee deciding the swarm’s direction. Decisions, in both cases, are emergent.

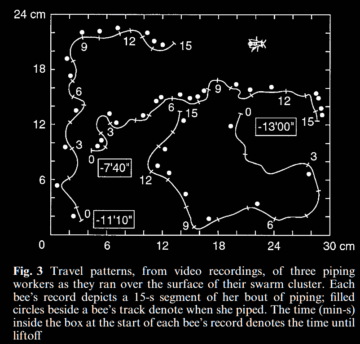

When the success of the group depends on unity, evolution refines the art of moving as one. What might appear as blind imitation is actually sophisticated coordination that reveals itself upon closer examination. Consider synchronized takeoff: flight muscles require precise temperatures to function, but the outer edge of a swarm can be 10°C cooler than the center. How do thousands of bees launch as one? Through another kind of piping, “reminiscent of the revving of a racing car’s engine” according to Seeley. The piping related to takeoff is a longer more complex dance compared to the tremble dance. A few worker bees run across the swarm surface starting one hour before takeoff, piping with increasing intensity. Upon hearing this signal, bees will start to shiver to warm themselves and the swarm up to flight temperature. Flight isn’t just an individual act. The hive’s capacity to launch as one reveals how even flight, at scale, becomes a social phenomenon.

Synchronized action is also necessary in the hive. Honeybee success in the management of thermal regulation is largely social. In summer honeybees maintain the hives at about 35°C, which corresponds to optimal metabolic conditions, while higher temperature would be dangerous for larvae. When too cold, the hive shivers. Regulation is done either via deliberate “shivering” of bees that activate their flight muscles without wing movement to generate heat. Alternatively, when too hot, the hive sweats. Bees collect and disperse water in the hive or at the hive entrance. Then they collectively fan their wings at the hive entrance to assist cooling via airflow and evaporation of water. This collective action is even more essential in winter. Because of their high surface-area-to-mass ratio (about 100 times greater than ours) bees lose heat rapidly. Alone, they wouldn’t survive the winter. Together, they do.

Seeing anew sometimes requires a closer look. But the reward is a richer, more astonishing world. One in which a creature the size of a paperclip remembers landmarks, communicates and optimizes its path across fields of flowers. One in which a swarm is not mindless instinct but collective intelligence.

In our next article, we continue tracing the invisible thread that shapes physiology, environment, and behavior across species.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.