by Jochen Szangolies

Stephen King’s Dark Tower-series takes place in a world that has ‘moved on’, and appears to be deteriorating. The story’s main protagonist, Roland Deschain, last of an ancient, knight-like order of gunslingers, is seeking the titular Dark Tower, which forms a sort of nexus of all realities, to perhaps halt or even reverse the decay. His greatest fear is that once he reaches the top of the tower, he finds it empty: God or whatever force is supposed to preside over the multiverse dead, or absent, or perhaps never having existed in the first place.

There is substantive debate on what forces shape history: the actions of great leaders, the will of the people, material conditions, conflict, or perhaps other forces entirely. For our purposes, however, we can group these into two categories: the microcausal view, where history is nothing but the sum total of millions upon millions of individual actions, and the macrocausal view, where there exists some form of overarching driver of history, be it fate, a Hegelian world spirit, or some form of laws of history that dictate its unfolding. This second option is perhaps most simply explained by there being an occupant to the room at the top of the Dark Tower: some entity that, by whatever means or design, holds the reins and shapes the course of the world.

In today’s world, this is a less widely held opinion than might have once been the case. But does this mean that history is just comprised of actions at the individual level, and it is thus this level that we should best appeal to for explanatory force? Is there, as Margaret Thatcher claimed, ‘no such thing as society’?

My aim in this column is to investigate the possibility that there is a middle being excluded here. Just as the theory of evolution has shown us that there can be design without a designer, I propose that, at least in certain respects, there can be a sort of ‘plan’ without a planner to history—that, in other words, it can make sense to analyze its course as if it were following a design not reducible to the actions of individuals.

We are all familiar with the fact that the objects of the real world—chairs, tables, cups of coffee and the rest—can be described at multiple levels. I am a human being, comprised of skin, blood vessels, organs, and bones (and a great number of bacterial and fungal microorganism passengers), which are in turn built up from cells, possessing nuclei and various organelles, within which a dance of molecules—proteins, DNA, RNA—orchestrates the chemistry of life, which can in turn be further analyzed into atoms, protons, neutrons and electrons, then quarks, and then, nobody knows. Each of the layers further down grounds higher-tier concepts: the way we walk and talk, think and speak would not be explicable without understanding the function of myofibril in muscle contraction, or the electrochemical transfer of signals across the synaptic cleft between neurons in the brain.

Yet the most committed reductionist would not start with the dynamics of quarks to try and explain human behavior: the higher levels, too, add something vital to our ability to make sense of the whole thing. However, it is challenging to pinpoint, exactly, what it is that the higher levels contribute—how something can emerge that is relevant without looking too much like magic. Most attempts either fall short, leading to nothing interestingly new, or end up being way too strong, effectively producing arbitrary new effects at higher scales. This is the ‘strong vs. weak’-dilemma: either, the lower level facts fully determine those on the levels above. But then, it’s hard to see what those upper tiers contribute. Or, the facts on the lower level fail to do so. Then, we are uncomfortably close to losing predictivity: in principle, upon a novel combination of lower-level elements, anything at all might happen—such that the right combination of dance steps and chants around a fire at the right time might actually produce rain the next day.

But here, too, there may be a middle ground: a notion of emergence capable of yielding genuine novelty, at least on the descriptive or explanatory level, without issuing an ‘anything goes’ carte blanche. That notion is causal emergence, which yields a tool to not only define a notion of higher-level novelty, but also, to precisely quantify it. To discuss it, we will first need to have a look at the notion of causation.

Whys, Hows And Wherefores

A good first-order approach to causation conceives of it as determining why stuff happens. That is, for any event, its causes are those events that made it happen. This seems like a straightforward enough notion, yet the deeper one digs, the more problematic it seems to get. The Scottish philosopher David Hume noted that actually, causation never figures in our experience; we merely find certain events in ‘constant conjunction’. Bertrand Russell, with characteristic verve, deems the notion entirely suspect and best excised from philosophy:

“The law of causality, I believe, like much that passes muster among philosophers, is a relic of a bygone age, surviving, like the monarchy, only because it is erroneously supposed to do no harm.”

However, for present purposes, we need not concern ourselves much with these philosophical issues. We can treat causality as effective: certain things reliably happen following certain other things; if I tip the mug over the edge of the table, it will fall and shatter. That is just a fact of life, and we should do well to take account of it.

Causation, however, does not always mean an all-or-nothing relation. One event alone may not be sufficient to bring about a certain effect, but may do so in concert with others, which themselves are not individually sufficient. Clouds in the sky may not necessarily foretell rain, but observing a cloudy sky as opposed to a clear one may lead you to adjust your estimation of the likelihood of rain upwards, making it reasonable to carry an umbrella. Thus, events may increase the probability that a certain effect occurs, without necessarily raising it to unity. Causal relationships, in general, are probabilistic.

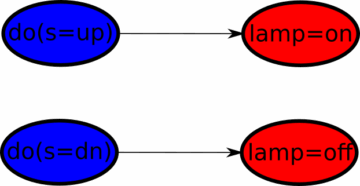

Let’s look at a simple example of a causal system: a light switch. When you flip the switch, you effect a subsequent change of state in, say, a light bulb. Flip it up, the light goes on; flip it down, it goes off. The causality here is deterministic: in particular, from the state of the light bulb, the state of the switch can be directly inferred. It also supports robust counterfactuals: had the state of the light switch been different, the state of the lamp would have been another, too.

This yields an operational criterion for something to be a cause: if a difference in one event entails a difference in another, then the first is a cause of the second. This is the key insight of the interventionist model of causation, in its modern form most closely associated with the work of James Woodward and Judea Pearl. In particular, the latter’s introduction of the do(x)-operator has brought about a rich formalism for the study of causal relationships.

It is useful to represent causal relations in the form of diagrams (directed acyclic graphs) that represent the flow of causality. In our present case, such a diagram, with the action of the ‘do’ operator highlighted, would look like this:

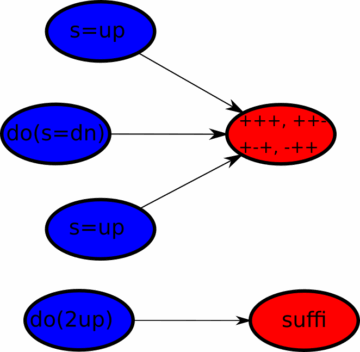

Now suppose you have a slightly more complicated setup. You have a room with three light bulbs; to read, i. e. for it to be ‘sufficiently bright’, at least two of them should be on, and you don’t care which. There are three switches on the wall; however, each individual switch fails to be deterministically connected to any of the three lamps. Through experimentation, you find that each of the possible switch positions {uuu, uud, udu, duu}, with ‘u’ for ‘up’ and ‘d’ for ‘down’, leads to one of the light configurations {+++, ++-, +-+, -++}, where ‘+’ means ‘bright’ and ‘-’ means ‘dark’—that is, to ‘sufficient illumination’. However, these seem to be entirely randomly connected, meaning that for each switch combination from the former set, one of the light configurations is realized with equal probability.

There is thus no causal relation between the switch-configurations and the lights—each of the switch settings could lead to each of the light patterns equally. In particular, flipping a single one of the switches will not change matters, so none of the switches’ states is causally related to the lamp states.

But clearly, there must be some causal relationship somewhere! We can, in fact, reliably produce a desired effect: illuminate the room sufficiently by flicking (at least) two switches up. This can be framed as a robust causal relation! What we need, here, is a change of scale: rather than taking account of the microstate—uud or udu or what have you—we ‘blur our vision’ and see only that ‘(at least) two switches are up’ (‘2up’ for short). And on this macroscale, suddenly, we have a perfectly deterministic causal relationship: 2up reliably leads to sufficient illumination (‘suffi’) (two or more lamps being on). We have a case of what neuroscientist Erik Hoel calls causal emergence (for a more in-depth overview, see here): while no causal relation exists on the microscopic scale, there is a macroscopic description that features a stable causality—something new that only becomes apparent at the right scale of description.

The Hand Of Fate

The notion of causal emergence accomplishes two things: first, it yields an example of nontrivial emergent features that nevertheless aren’t magical, thus landing in the middle between weak and strong notions of emergence. But additionally, it yields a reason to describe systems in terms of a certain macroscale: because at that scale, we can describe the system’s behavior by means of simple, causal laws. There is a good reason not to care so much about the underlying microdynamics of our switches-and-lamps system: the macro-level description simply is much more informative and possesses greater explanatory power.

Now, the above system is, of course, rather contrived. But similar phenomena exist also in more natural situations: just think about how, at the bottom, the machinery of DNA translation is fueled by millions of random interactions, molecules bumping into each other, sticking together, winding around one another. But to describe matters at this level would be hopeless; rather, it is far more illuminating to speak of RNA-polymerase ‘moving’ along the DNA-double helix, ‘unzipping’ it and ‘assembling’ proteins according to the plan presented by any given gene.

Note how, almost unavoidably, agentic and even teleological language enters into the picture: we are talking about the action of an enzyme as if it were following a plan with some goal—the creation of a particular protein—in mind, while ‘at bottom’ we really have nothing but random molecular interactions.

Suppose now you are one of the light switches in our example. On the macroscopic level, you have little if any agency: your own decision, your own state, has no immediate causal consequences. Yet, the overall system you are part of—your society—shows a clear and purposeful behavior. It is as if there is an unseen force that directs the course of history, an agency not reducible to that of its actors: the force of fate, a divine plan, almost. But if this is a plan, it is one without a planner: there is noone in the room atop the Dark Tower; the throne there is empty.

This introduces a third, ‘middle-ground’ option for the explanation of the arc of history: something that has all the trappings of design, of scheme and plan, but without there ever being any concrete agency to come up with that design. This weakens the grounds for an inference that, I believe, all of us make regularly: that from the observation of a pattern of historical events apparently directed at the realization of a particular goal, it follows that there must be some agency (perhaps a shadowy cabal secretly holding the strings behind the scenes) whose goal is thus realized. That is, it lessens the pull of conspiratorial thinking: while events may unfold as if secretly orchestrated, there is no need to appeal to a hidden intention to explain this appearance. I call this the emergent conspiracy, and I believe it constitutes an important check on the machinations we see at work in the unfolding of historical events—any perceived conspiracy may just be an emergent pattern. (Of course, this does not mean that there is never any (nefarious) design woven into the strands of history.)

Pick The Cherry, Fell The Tree

There is a flipside to the above: where conspiratorial thinking involves a large-scale teleological force where none exists, some accounts of history single out a microcausal explanation which only superficially accounts for the data. The reason this is possible is that (strategically or accidentally) excluding parts of a causal network may strengthen apparent causal relationships, thus attributing causal responsibility where none exists: the causal power of a given node is strengthened in a spurious way by neglecting other parts of the network.

Consider a murder trial in which the suspect is shown to be at the scene at the time of the murder, to have had access to the murder weapon, to have had a motive, and so on: the case starts to look rather solid. But then suppose that there exists a video recording of the event, where a third person is seen to surreptitiously obtain the weapon, commit the crime, and replace it: obviously, the original suspect is fully exonerated. But a malicious entity, intent on pinning the crime on them, could easily do so by merely removing the exculpatory evidence. Importantly, nothing needs to be fabricated in order to do so: all the best lies are told in terms of nothing but the truth.

We could easily make it seem as if one of the switches in the above story controls the illumination of the room. All we need to is simply hide the state of the other two; if one of them is on, the flipping of the switch under scrutiny then would appear to, deterministically, control whether the light is on. Thus, a thread of causality only present on the macro-level appears to be ‘pulled down’ to the micro-level by judicious selection of focus.

I believe that many ‘single-cause’ explanations of historical events are of this kind—although in the vast majority of cases there is probably no ill intent present (indeed, there may be a second-order effect here: an emergent conspiracy of spurious attributions of causation). Of course, there are explicit examples of such ill intent, with populist or propagandist aims, most often those blaming some minority for the economic/social hot button issue du jour; but in general, the net of causation of any historical event of note is so vast as to defy individual analysis. But this does make a case to view any individual source of explication with some suspicion: even without meaning to, in general, any single analysis probably will be beset by the problem of spurious causality to some degree. Causal cherry-picking is near inevitable, even with the best of intentions—and provides a valuable tool to those with less wholesome aims.

The framework of causal emergence, applied to the explanation of historical events, urges that at least in some cases, this explanation can and should be sought on the macro level, even in the absence of any directing forces on that level. The appearance of design does not imply a designer, a lesson already familiar from evolution (which indeed can be seen as a paradigm case of causal emergence). Yet, agentic or even teleological language may provide the best frame for historical trends at this level. Twin fallacies lurk: the reification of large-scale causality in terms of similarly large-scale actors, be they shadowy conspiracies or divine direction; and on the other hand, the hasty pull-down to micro-level explanations by cherry picking nodes from the causal network. Any serious analysis of historical developments would do well to try and steer clear of either.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.