by Claire Chambers

Entering Delhi’s famous Sunday Book Market – known locally as the Patri Kitab Bazaar – in Daryaganj is to step into another world. Previously a tangle of tarpaulin stalls behind Jama Masjid, it has been moved to a gated compound called Mahila Haat. In her new Cambridge University Press Element titled Old Delhi’s Parallel Book Bazaar, Kanupriya Dhingra treats this market as an improvisatory ‘location for books and a site of resilience and possibilities’.

Dhingra, a South Asia print historian who earned her PhD at SOAS (University of London) and now works as a professor at BML Munjal University, passed much of her life as a young adult among these booksellers. In our interview she explained that her middle-class family had not given her a particularly bookish childhood. Yet, as a student searching for texts to ‘help with passing exams’ and then as a researcher, she was unexpectedly introduced to the neglected but fascinating subject of parallel book bazaars. Over years of fieldwork, she came to realize that these markets encapsulate Delhi’s historical, economic, and socio-political currents. The result is a 92-page minigraph that fuses memoir, reportage, and analysis to tell the bazaar’s story. It reads at once as a colourful ethnographic diary and an invitation to imagine an alternative literary landscape.

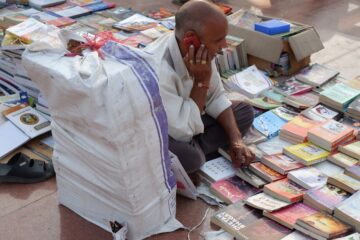

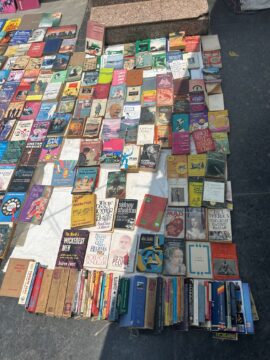

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called The Vicious Case of the Viral Vaccine. This scintilla of serendipity – arising from what she calls ‘double chance encounters’ – defines the market.

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called The Vicious Case of the Viral Vaccine. This scintilla of serendipity – arising from what she calls ‘double chance encounters’ – defines the market.

Dhingra declared: ‘it was important for me to show the spirit of the book market through the language in which it speaks’. In practice, that meant archival work, years of interviews, and what she follows Henri Lefebvre in calling rhythmanalysis – charting the market’s weekly cycle from dawn-packed piles of printed matter to its dusk-time cleanup.

The bazaar isn’t only English textbooks (sold cheaply by weight) or Bollywood posters – it is a polyglot shelf. One stall may spill out Hindi pulp thrillers, its neighbour offering up second-hand Urdu novels, while another is festooned with European fashion magazines. Old Delhi’s Sunday bazaar is metonymic of India’s literary and linguistic pluralism, from regional genre fiction and ephemeral comics to academic guides and imported children’s picturebooks.

This multilingualism is carried over into Dhingra’s own methods. The book overbrims with Hindi words, especially in the subheadings. (She also used her mother tongue of Punjabi to talk to a Sikh seller.) Such key terms as नयी जैसी naiyi jaisi (like new, or second-hand) are parsed in attentive detail. I asked Dhingra how South Asian languages came into her methodology and research. She responded that it was crucial to reflect the market’s spirit by including some Hindi, avoiding academic jargon, and giving due regard to local idioms and an ungrammatical but vivid use of Hinglish.

In the book, Dhingra describes how the bazaar once sprawled chaotically along Aruna Asaf Ali Marg and Netaji Subhash Marg, only to be ferried in 2019 to the semi-permanent haat nearby. The State aimed the 2019 move to Mahila Haat as a sanitization of the area. The transfer was double-edged. Some vendors saw it as an upgrade and enjoyed the new space’s ‘glamour’ – a word that crept up with both positive and negative connotations in several of her interviews. Other respondents felt it neutered the bazaar and stripped it of its authenticity, turning the place into an ‘Instagrammable’ simulacram.

The vendors negotiate, and sometimes resist, city regulations in order to keep their parallel book world alive. Dhingra even participated in the 2019 protests against relocation, adapting her methods to include media coverage and direct involvement with the booksellers’ own efforts. She passionately spoke of the movement of protecting the book bazaar:

The protesters’ shared rhetoric of joy became part of my methodology, and helped me find new ways to perform book history. The struggles of the vendors and the fragility of the space were in front of my eyes. The ability of the bazaar to enable joy and movement meant that lagaav or attachment seemed to be a crucial part of its affective power.

Running the Patri Kitab Bazaar necessitates an intermixing of that लगाव lagaav (attachment) of which she and her interviewees spoke, stirred together with शौक़ shauq (hobby or passion). But, above all, a seller is motivated by the need for रोटी roti (livelihood). We should be under no misapprehension but that this is labour. Moreover, it is a work which tacitly defies the notion that books must only circulate through formal channels. In rich, often lapidary prose, Dhingra shows readers how the vendors regard their trade not as mere street hawking but a ‘sophisticated’ cultural industry.

Running the Patri Kitab Bazaar necessitates an intermixing of that लगाव lagaav (attachment) of which she and her interviewees spoke, stirred together with शौक़ shauq (hobby or passion). But, above all, a seller is motivated by the need for रोटी roti (livelihood). We should be under no misapprehension but that this is labour. Moreover, it is a work which tacitly defies the notion that books must only circulate through formal channels. In rich, often lapidary prose, Dhingra shows readers how the vendors regard their trade not as mere street hawking but a ‘sophisticated’ cultural industry.

Reading Old Delhi’s Parallel Book Bazaar is eye-opening and affirmative. I came away marvelling at how much serendipity and strife can be crammed into a few city blocks every weekend. Dhingra’s writing is warm and grounded as she describes these vagaries and vicissitudes. She gives vendors their real names, and volunteers a few of her own reactions. Far from a desk-bound academic, this is an intrepid flaneuse who admires the booksellers’ expertise but also respects their everyday anxieties. Hers is an intimate portrait that reads more like narrative nonfiction than academic treatise.

In the end, the value of Dhingra’s slim volume lies in showing us that this market is more than a place to bargain over tattered texts. It’s a lesson in popular culture and metropolitan coexistence. Old Delhi’s Parallel Book Bazaar is for anyone who loves books – or who cares about cities and the people who populate them.