by Chris Horner

In daily life we generally get by without invoking explicit moral positions or judgements. This is because, for the most part, the norms and taboos of the quotidian life are just embedded in what we do or say. This isn’t to say we all adhere to them all the time – far from it. But when we see such behaviours our responses will range, according to seriousness, from tutting to calling the police. At one end we have the norms and taboos of basic politeness, at the other the serious stuff about harm. But this mainly happens without anyone needing to invoke an explicit moral a code, since our responses are embedded in the ‘ethical substance’ of everyday life.

But there are times when we may ask ourselves whether a norm or taboo or a rule is right. We seek justifications. Then we might ask about the consequences of following a rule, or of the red lines that might mark real moral obligations and limits. Things that appear as ‘common sense’ can turn out to be abhorrent – it was once ‘common sense’ to think that women shouldn’t be educated or that some races were ‘obviously’ superior to others. So, we need to be able to critically reflect. Even then moral philosophers like Kant and JS mill are unlikely to come up. It’s more likely to be the ‘Golden Rule’ (do unto others as you would have them do unto to you) or the ‘what would happen if we all did that?’ Such reflections conduct have their place. We should reflect on what we do, and maybe change it, or call for change.

But everyday ethical life isn’t based on such things. It is the other way around: moral talk is rooted in ethical life, most of which happens without much reflection. We don’t go around with propositions about morality ‘in our heads’, as it were. We just live our social lives. Moral maxims and theories are reminders of what we should consider, what matters, and we reach for them we when feel stuck. Explicit ‘moral talk’ is parasitic on that other stuff of everyday life – the practices and institutions that we don’t put into question most of the time, what Hegel calls Sittlichkeit.

Moralising

Moral judgment can go wrong, as well as right. It goes wrong when we exchange morality for moralising. I’m thinking here of judgment directed not at actions but at the people we have a problem with. Someone is viewed as having crossed a line and is cancelled or hounded. Perhaps they have done something wrong: judgment has its place. But at its worst a mob mentality can set in – and the internet is particularly good at amplifying group hate for persons deemed beyond the pale. Moralising is a temptation: it allows us to direct our condemnation at others, who may represent aspects of ourselves that we would rather not think about. All too often this resembles the attitude of the executioner, a hangman morality.

This is not an argument against making moral judgements. But it would be wise to keep them on a tight leash. In an imperfect society, with flawed families full of imperfect people we often don’t know why we do things, or what drives us. Each of us has an unconscious, and buried parts of childhood that push us this way or that and can incline us to act in ways damaging to ourselves and others. We do not have a transparent, rational, and coherent moral self; individuals are inherently opaque to themselves due to their embeddedness in social structures and histories that precede them. That doesn’t mean we should never judge or condemn, but judgment needs to be tempered with compassion, and some humility about how much we don’t know about ourselves and others.

Politics

The other place where it seems to me that we get it wrong around morality, is when we try to tackle politics as if it were an extension of everyday moral issues. Moral judgment certainly has a place in our politics – how could it not? But again, it is too easy to go wrong here. Reducing politics to morality—to individual judgments of right and wrong—misses the complexity of political life. A purely moralistic approach to politics is inadequate and potentially destructive. I think Hegel grasps this rather well. For him, politics properly concerns itself with the institutional arrangements that mediate human freedom in society. Unlike moral philosophers who begin with abstract principles or individual conscience, Hegel recognised that political understanding must grapple with the concrete social institutions through which human freedom becomes actualised in the world.

Moralism—the tendency to reduce political questions to matters of individual moral judgment—fails on several counts. First, it misunderstands the nature of political problems. While moral thinking concerns itself with the intentions and conscience of individuals, politics deals with the objective structures that shape collective life. Moralistic politics frequently devolves into what Hegel would recognize as the “beautiful soul” syndrome—a stance that preserves moral purity by standing apart from the messy compromises of actual political engagement. Yet this position ultimately proves empty, as it cannot translate its abstract principles into concrete reality. About the best it can do is judge others for their failures to be good and maybe do a bit of gesture politics – boycotting coffee chain A or calling for the cancellation of person B.

Universals and Particulars

Hegel’s concept of the “concrete universal” offers an alternative to moralistic abstraction. Rather than beginning with abstract moral principles that float above social reality, Hegel insists that universality must be embodied situations and institutions that mediate between individual and collective interests. The state, for Hegel, represents not a moral entity but rather the institutional framework within which freedom becomes concrete. It is not the expression of moral will but the rational organisation of social life – or should be. Reducing the state to a moral actor misunderstands its essential function.

When politics becomes mere moralism, it loses sight of these institutional mediations. Political opponents – and sometimes possible allies – become not representatives of different interests or perspectives but embodiments of moral evil. It transforms politics into a Manichean struggle between good and evil.

It is too easy to identify corrupt politicians and greedy billionaires as the problem. They are a problem, a big one, but as symptoms, not malefactors such that all would go well if they were swept away. Moralistic approaches focus on individual behaviour rather than systemic issues. For instance, addressing climate change requires structural transformations rather than merely encouraging personal responsibility. Billionaires, along with global warming, steepening inequality and more, are products of a system, capitalism. Moral condemnation of individuals can’t get close to grappling with that.

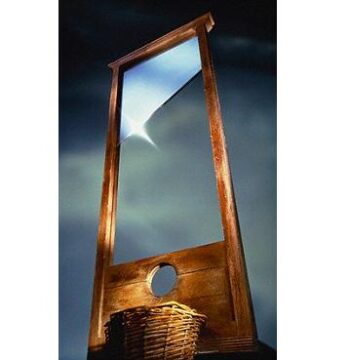

Universals matter. We invoke the universal when we demand justice. But particulars matter, too: the different people that we are, the various ways we live our lives. If we emphasise one at the expense of the other, we can go into some very dark places. Moralistic politics tends to deny legitimacy to particulars, seeing them only as expressions of selfishness. This failure to recognize particularity as an essential moment in political life leads to an abstract universalism that, ironically, becomes tyrannical in practice. The Terror of the French Revolution—which Hegel analysed in the Phenomenology of Spirit—exemplifies this danger. When politics becomes pure virtue, all opposition becomes vice to be eliminated. The guillotine becomes the instrument of abstract moral judgment unleashed on the political realm.

Universals matter. We invoke the universal when we demand justice. But particulars matter, too: the different people that we are, the various ways we live our lives. If we emphasise one at the expense of the other, we can go into some very dark places. Moralistic politics tends to deny legitimacy to particulars, seeing them only as expressions of selfishness. This failure to recognize particularity as an essential moment in political life leads to an abstract universalism that, ironically, becomes tyrannical in practice. The Terror of the French Revolution—which Hegel analysed in the Phenomenology of Spirit—exemplifies this danger. When politics becomes pure virtue, all opposition becomes vice to be eliminated. The guillotine becomes the instrument of abstract moral judgment unleashed on the political realm.

This doesn’t mean that the particulars ought to be promoted at the expense of universal claims. That is the problem in the kind of identity politics that is so often mixed in with moralism. People on the political left would do well to steer clear of it. ‘Idpol’ is, in fact a characteristic of the political right – nationalism, racial supremacy and bigotry emanate from the assertion of the particular over the universal. It would be good for those opposing such things to see that justice claims invoke universals – but that the universal comes, in abstract form, but through the concrete instances in which justice is lacking. So ‘Black Lives Matter’, for instance, should be understood as a universal claim, not the promotion of one group against others. BLM protested that justice has not been extended to some people.

Politics requires not moral purity or the implementation of a pre-established moral vision. An effective approach to politics would move beyond moralistic denunciation to engage in the difficult work of making the world a better place. It would recognise that freedom emerges not through moral condemnation of existing arrangements but through their dialectical transformation, whether through reform or revolution. In our age of moralised political discourse, Hegel’s perspective offers a vital corrective—one that promises not moral simplicity but something more valuable: political wisdom.