by Monte Davis

Climate change first came to many Americans’ attention in June, 1988. James Hansen, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, testified to the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources that the signal of long-term warming from increasing CO2 in the atmosphere had emerged unmistakably from the noise of year-to-year variation in weather.

Four of the warmest years on record had come earlier in the 1980s, and 1988 would be another. One wildfire after another had begun to spread in Yellowstone Park. As that summer advanced, what would be a historically severe and costly three-year-drought took hold in most of the United States.

How long had this moment been coming? The unmatched resource for answers is Spenser R. Weart’s superb 2003 book The Discovery of Global Warming, and its greatly expanded, steadily updated, richly linked hypertext version online.

In 1824, Joseph Fourier reasoned quialitatively that the atmosphere must let the sun’s visible light in more readily to warm the earth than it lets that warmth out as infrared radiation.

In 1859, Joseph Tyndall identified water vapor and carbon dioxide, CO2, as the most important components that absorbed — “trapped” — and re-radiated downward some of the infrared energy.

In 1896, a century into the industrial revolution and its hunger for fossil fuels, Svante Arrhenius calculated very roughly that a 50% increase in CO2 would warm the planet on average by 5° to 6° C. The good news is that his estimate was almost four times too high. The bad news is that the next century of the Industrial Revolution – and more coal and more oil and gas, and population growth – blew out all expectations. Arrhenius speculated such an increase would take many centuries, but we will reach it in 2026. And keep going.

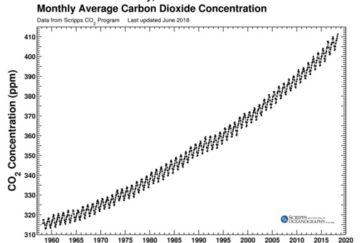

In 1958, C. David Keeling’s precise measurements from Hawaii began documenting the steady year-by-year increase in the eloquent, ominous graph we’ve come to know.

In 1958, C. David Keeling’s precise measurements from Hawaii began documenting the steady year-by-year increase in the eloquent, ominous graph we’ve come to know.

In 1967, a National Academy of Sciences report on “Energy and Climate” listed potential consequences of global warming for sea life and ocean fisheries, sea levels and coastal cities, rainfall patterns and timing, and agriculture everywhere. “World society could probably adjust itself, given sufficient time and a sufficient degree of international cooperation. But over shorter times, the effects might be adverse, perhaps even catastrophic.”

In 1977, the newly formed U.S. Department of Energy began to draw together what had been scattered programs into a much more intensive series of research programs and meetings that were intended to drive policy decisions in the near future rather than the sweet by-and-by.

***

How long had I seen it coming? Not as long as I should have, although well-educated in science and a writer for popular science magazines since the early 1970s. I didn’t write about climate, although I had some grasp of the state of the art in AGW. Then, as interview editor at a new magazine, I assigned myself to find some interview opportunities at (take a deep breath) the Department of Energy’s Carbon Dioxide Effects Research and Assessment Program’s Workshop on Environmental and Societal Consequences of a Possible CO2-Induced Climate Change, conducted by the AAAS in Annapolis, MD in April, 1979.

The experience of the five-day conference was like drinking from a fire hose. This was your idea, I reminded myself, Do try to keep up. The printed proceedings ran to 120 pages of distilled discussions and consensus (sometimes) from five panels on the state of the science, likely social and institutional responses to warming, and “issues associated with analysis of economic and geopolitical consequences” – i.e. translating the findings into scenarios for policy makers to consider and act upon before the consequences of climate change became acute. Plus 350 more pages of 28 invited papers, adding background and detail to what participants were telling each other “live” in the panels, so that they could listen and think more instead of taking notes.

Late one afternoon on the fourth day of the conference, five of the most knowledgeable and respected participants gathered for a group interview. All have died since. They were:

Walter Orr Roberts (1915-1990) — Astronomer, astrogeophysicist, prime mover and first director of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Colorado, AAAS president 1969, director of the Aspen Institute program on Food, Climate and the World’s Future, 1974-1981, author with Henry Lansford of The Climate Mandate (1979).

Walter Orr Roberts (1915-1990) — Astronomer, astrogeophysicist, prime mover and first director of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Colorado, AAAS president 1969, director of the Aspen Institute program on Food, Climate and the World’s Future, 1974-1981, author with Henry Lansford of The Climate Mandate (1979).

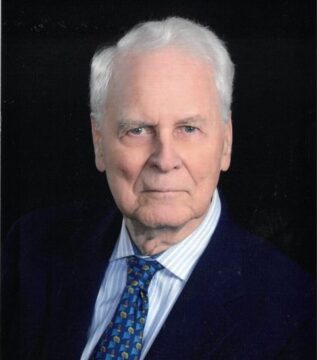

Paul Waggoner (1923-2022), Army meteorologist in WWII, student and professor of agronomy, plant physiology, and soil sciences at U. of Iowa and U. Of Chicago, researcher and then director at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, author of more than 180 much-cited papers over six decades.

Paul Waggoner (1923-2022), Army meteorologist in WWII, student and professor of agronomy, plant physiology, and soil sciences at U. of Iowa and U. Of Chicago, researcher and then director at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, author of more than 180 much-cited papers over six decades.

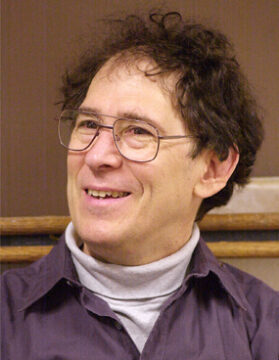

Stephen Schneider (1945-2010), atmosphere & climate modele r, NCAR staff 1973-1996, interdisciplinary professor and senior fellow at Stanford, founder and first editor of Climatic Change, author of The Genesis Strategy (1975) and other books, scientific adviser in five administrations, MacArthur “genius” grant 1992.

r, NCAR staff 1973-1996, interdisciplinary professor and senior fellow at Stanford, founder and first editor of Climatic Change, author of The Genesis Strategy (1975) and other books, scientific adviser in five administrations, MacArthur “genius” grant 1992.

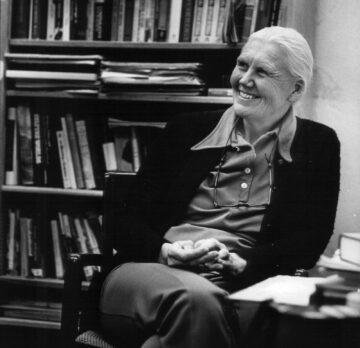

Elise Boulding (1920-2010), sociologist and chair of Dartmouth’s sociology department, a formative figure for decades in peace and conflict studies as well as the history of women’s social roles, partner in a long marriage/collaboration with the influential English economist Kenneth Boulding.

Elise Boulding (1920-2010), sociologist and chair of Dartmouth’s sociology department, a formative figure for decades in peace and conflict studies as well as the history of women’s social roles, partner in a long marriage/collaboration with the influential English economist Kenneth Boulding.

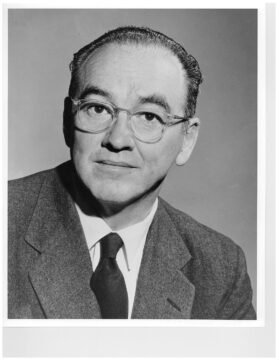

Roger Revelle (1909-1991), dean (and in many ways leading creator) of American oceanography, called by the NY Times “one of the world’s most articulate spokesmen for science.” Graduate student, then researcher, then director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography; leading advocate for the creation of the U. of California’s San Diego campus in 1960, then founding director of Harvard’s Center for Population Studies 1964-1976, then UCSD again as Professor of Science and Public Policy; AAAS president 1974, National Medal of Science 1990.

Roger Revelle (1909-1991), dean (and in many ways leading creator) of American oceanography, called by the NY Times “one of the world’s most articulate spokesmen for science.” Graduate student, then researcher, then director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography; leading advocate for the creation of the U. of California’s San Diego campus in 1960, then founding director of Harvard’s Center for Population Studies 1964-1976, then UCSD again as Professor of Science and Public Policy; AAAS president 1974, National Medal of Science 1990.

***

Roberts and Waggoner were the first to arrive in a quiet corner of the hotel restaurant. They discussed the adaptation of agriculture to new territories and conditions:

Waggoner: One climatologist told me that he gets many more requests for reprints of his papers from Canada than from the US, in spite of the population disparity. The cooler and more marginal your croplands, the more you care about climate.

Roberts: The USSR is also deeply concerned with the CO2 question, because of its bearing on the length of the growing season. And they’re worried about the short-term cooling since the 1940s, which isn’t well explained, and which has produced hardship already for them. For two years now, the harvest time has been very adverse — cold and wet — which makes it impossible to get a lot of the wheat in.

Waggoner: The trouble is that as the temperature goes down, the number of growing degree days goes down, and the plants move through their phenological stages more slowly, as well as having a shorter period to do it in. So you choose another variety, one that can get by with a shorter growing season. That way you don’t have a disaster, you just have a decrease in yield. If the weather changes drastically from year to year, you’re up against it: do you try to minimize risk or maximize yield? Generally the wealthier the country, the more storage is available, so they go for maximum yield. The poor have to minimize risk.

Roberts: In 1975 the Soviet wheat crop suffered a 30% decline overall, with a nearly complete wipe-out in some areas. Both the rainfall and the length of growing season are highly variable, particularly in the new agricultural lands.

Waggoner: On the other hand, the variance in yield was a lot less because they had the Ukraine averaged in, too. If you have a big nation, you can cope with the variance. We have our wheat belt, but it could be shifted as it has been in the past. At one time little Connecticut was called the “Provision State” because it provided the wheat to feed the Continental Army. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, New York was the big wheat-growing state. There can be a lot of agricultural potential unused in a big country.

Enter Elise Boulding, Stephen Schneider

Q: What domains other than agriculture face important impacts from climate change?

Schneider: The first is simply the ocean level; if there’s a rise because of melting Antarctic and Greenland ice, which is being argued now as a possibility, people will have to move away from what are now densely populated coasts.

Another is a possible extension of the range of tropical diseases, as the freeze or chill line that stops their carriers is pushed polewards: schistosomiasis, the tsetse fly, and so on.

Roberts: There will be intensified competition for water for all uses. Already we’re seeing severe competition between agriculture and other water uses in California and the Colorado River basin. We’re getting our noses rubbed in the fact that the U.S. west was settled in an unusually wet period.

Boulding: There’s also the impact at the household level, assuming that agricultural effects make food more expensive. People will have to find various adaptive strategies in order to compensate. Think about the normal “strategies” that people use in the course of a year anyway: the range of behaviors that takes us from January through December, in eating, clothing ourselves, recreation — not crisis strategies at all, but they give us a great response capacity. Households – especially low-income households — will have to compensate for all kinds of impacts from climatic change, but we don’t always recognize how responsive they can be.

Waggoner: Responsiveness is also the most important thing about agriculture and the weather. What you do if you know a change is coming, and you’re going to need new varieties but you don’t know what kinds, is to tune up and improve the system that produces new varieties. Response times can be fast, as in the creation of the soybean industry in Brazil: within five or ten years, that has become a major factor in their economy and the world crop picture.

Boulding: In our panel we heard about a good example of that in relation to Iceland, where the climate is marginal. Every time there’s enough warming for glacial retreat in the valleys, and grass shows up where it wasn’t before, the sheep and goat herds move in at once.

Schneider: Paul, I agree that any rational person faced with 10% interest rates would have to consider the present worth a great deal more than the future. But is that true for a rational nation? One of my students and I have looked at the dollar costs to the US of a 25-foot sea level rise. It comes out to something like a quarter of a trillion dollars, which outweighs the benefits of a great many fossil-fuel activities. But what if this sea-level rise isn’t going to happen for 150 years? Assume you’re going to have to spend money today to prevent it then, and settle on a discount rate; say, 7%. Work it out, and you find a quarter of a trillion dollars then is worth only seventy-five million now — not nearly enough to scare anyone away from fossil fuels.

Boulding: Most human experience comes in families, and if you can think of your descendants as part of your extended family, that brings them into your social reality — you’re willing to make allocations for your grandchildren that you wouldn’t make for posterity generally, or even yourself. We have to develop the idea of seeing descendants as part of our family, in order to generate an adequate level of caring. Otherwise, the discounting simply takes over.

Enter Roger Revelle

Revelle: Let’s not write off governments, Elise, frustrating as their inertia can be. It’s the nature of government to be concerned about the future. That’s what government is: the collective expression of a belief that the nation, the people, the society, is immortal. We all have loyalties to these immortal institutions; governments, corporations, universities.

If the more extreme potential changes come about, we’re going to need all hands on deck and working together. My panel talked about ocean warming and current changes moving major fisheries hundreds or thousands of miles, In places where fish is the main protein, that would be as bad as, say, the Indian Ocean monsoon failing, or worse. And if the fish used to be in my territorial waters and now are in yours…

Boulding: OK, but much of the concern comes through non-governmental organizations. They’ve grown exponentially in numbers since the beginning of the century. Every year now adds one or two thousand international public-interest groups, and each one has as its nucleating point a statement of concern that goes beyond both national borders and the present day.

Schneider: Just tagging on to what Roger said: Paul, you stress the adaptability of crops and quick response of farmers. But if crop growing zones are moving around, there’s also a lot of new infrastructure needed. We had a century to build up the roads and railroads and grain silos and irrigation and so forth that make our agriculture so productive. If we have to build it again in new places, and protect cities from rising sea level, and deal with the fishery changes Roger talked about, and a dozen other expensive challenges all at the same time…

Q: Can we collectively adapt fast enough? Do people realize the scale of it?

Schneider: At the beginning of any big policy shift, you get consciousness-raising meetings, and sometimes you have to say the same thing in fourteen different contexts to get people aware and to entrain the expertise from diverse disciplines that you need. I’d say we’re coming to the end of that phase on CO2 warming, although we still have some of it because it’s brought together such a wide range of physical and social scientists. Future meetings will be more focused on specific work. I must admit I’m getting fed up with consciousness-raising, organizing, and agenda-setting meetings, because I’ve been at it non-stop since 1971.

Roberts: One of the things that bothers me about the CO2 issue is it’s perceived by most people through scientific or technical or economic eyes, with almost complete disregard of the moral issues. Congress passes a resolution saying that food is a human right, but if you bring it up in conferences like this they say, “Well, we didn’t really mean it.” There’s no institutional mechanism to provide food as a right for everyone. Yet that symbolic action reveals a craving. If people believe that food aid will get to those who need it, food aid is forthcoming. There is a moral force for doing what is right. There is a latent sense of world community that’s coming into focus through issues like this.

Q: Edward Lorenz changed hopes for weather prediction twenty years back with the “butterfly effect.” The accuracy of prediction drops off rapidly no matter how good your initial data is. Does that have implications for climate as well as weather?

Schneider: We just don’t know. I helped build a climate model in 1973 that had a bifurcation. We found that if you extended the ice cover from the poles but left the amount of energy from the sun the same, there was a certain latitude around 30° beyond which the ice would keep spreading to the equator and cover the earth permanently — whereas if you brought it to 29°, it would snap back to its present condition. But that was one model, and we’ve been able to build other models, just as plausible, where that doesn’t happen.

Revelle: I’ve heard several times now that if the ocean should freeze over, that would be a permanent state from then on. So there could be two or more stable states for the climate to flip between?

Schneider: An ice-covered Earth might be stable for a long, long time – until enough CO2 from volcanism builds up to “break the spell” — because ice is so reflective. As long as you have blue water and green land in the tropics, even with white at the poles, that equatorial band is absorbing energy and pumping it north and south. It’s that fundamental heat engine that keeps our climate reasonably stable, even though there may be another equilibrium with everything ice-covered.

Boulding: So let’s hear it for the blue and the green!

***

45 years later — too many of those years wasted by climate change denialists, let’s-not-be-hastyists, and something-will-turn-upists — there’s a sharper, hotter, more urgent edge to “Can we collectively adapt fast enough? Do people realize the scale of it?” I owe this voice to their thoughts that day, not previously published because I failed to persuade my colleagues that a general audience needed more than another run-through of the “greenhouse effect”…

And encountered the same response at the next science magazine I worked at… and allowed the sense of urgency that I’d felt coming back from Annapolis to fade, year by year, because of course there were so many other urgent things to attend to. Plenty of good reasons.

I hope my first grandchild, due this month, will understand.