by Chris Horner

You can’t always get what you want

But if you try sometime you might find

You get what you need —Jagger/Richard

Writing free verse is like playing tennis with the net down. —Robert Frost

Life can be full of obstacles to getting what we want. But sometimes we get it, we get there, we get the thing we wanted: the lover, the career, the promotion, the house, the holiday, the PhD. Yet after all that effort, trying, searching and perfecting, to the final goal, the success we longed for, why is it so often a disappointment, something leaving us flat, even sad? Something is missing. It turns out getting what we want wasn’t what we really wanted. We wanted something else. But what else? Not being completely happy with what we actually get is part of the human condition: we just have to accept it, and tune our expectations better to meet the inevitable disappointments. There is truth in that, but also good reason to think that modern work and consumption is turning mild disappointment into something altogether more toxic.

Achievement Society

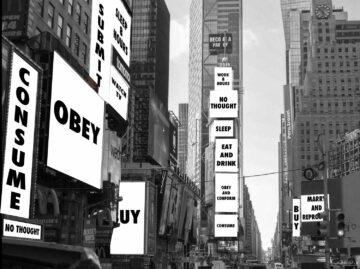

There is nothing new about having goals, and working towards them. Nothing new in finding that the things we thought we would get happiness from crumble in our hands as we touch them, and that doesn’t stop us from wanting things. One of the advantages of living in a prosperous part of the world is surely that such possibilities become open to more people: modernity is supposed to be about choice and opportunity. But a society so heavily pitched towards achievement of all kinds – in our careers, love lives, acquisition of things – has brought the experience of dissatisfaction to the level of a social pathology. Achievement has become a commandment, and endlessly receding horizon that entices as it frustrates. We live in an Achievement Society, in which we exploit ourselves in the pursuit of more, more of everything, more and more forever.[1] The result is a kind of blow out, an infarction of the self, depression, burnout, since no one can keep up the relentless pace of total achievement forever.

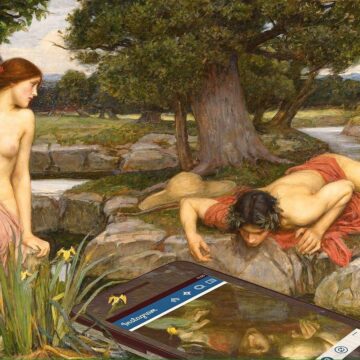

Our market society exacts a psychic cost arising from the constant stimulation of desires: desires to fill a lack that never gets stilled by anything we buy or do. And behind our desires lie unconscious drives, drives that push us on to the next thing, endlessly. A desire directs us to a thing, person or experience that we imagine will satisfy us. Inevitably, it doesn’t, or not for long. The missing thing that we suppose will complete us represents nothing so much as that pot of gold at the end of the rainbow: the closer we get, the more it recedes, since the thing we get only act as brief substitute for the Thing, a fullness that is forever unavailable to us. So the pursuit continues.

Our market society exacts a psychic cost arising from the constant stimulation of desires: desires to fill a lack that never gets stilled by anything we buy or do. And behind our desires lie unconscious drives, drives that push us on to the next thing, endlessly. A desire directs us to a thing, person or experience that we imagine will satisfy us. Inevitably, it doesn’t, or not for long. The missing thing that we suppose will complete us represents nothing so much as that pot of gold at the end of the rainbow: the closer we get, the more it recedes, since the thing we get only act as brief substitute for the Thing, a fullness that is forever unavailable to us. So the pursuit continues.

Drives and Desires

Drives and Desires

What lies in us is something that is more than the conscious subject can know: the drive. Drives lie below the conscious mind, and are not concerned with the acquisition of this thing or that event. If you were a golfer trying to pot the ball into a hole, the drive would be the invisible force field that wants to push the ball to circle around the hole, forever. For the drive, the game must never end. Finally getting the ball into the hole seems to be what we desire, but the aim of the Drive is something else and the ‘goal’ a mirage. Achieving the goal, the hole in one, means a brief exhilaration which must pass, leaving a sense that something more needs to be done, something else. The ‘win’ leads us wanting more. The same is true for that shiny thing you bought, or were given: the best part was unwrapping the packaging. After that, it hangs in the closet or the yard, while the hedonic treadmill drives you on to something else.

We can interpret that as a kind of misery. It need not be. For without this drive we wouldn’t be interested in anything. Lack, loss, and imperfection are necessarily part of any life. If total fullness was available to us it would be the end of us, since there are no events in the amniotic fluid of total satisfaction. Only the womb or the tomb has that. The important thing is to see this for what it is and to be satisfied with dissatisfaction. You don’t need the next new thing.

The Joy of Limits

The Joy of Limits

Capitalism makes this hard to grasp. The kind of market society we have is predicated on the creation of new wants, the stimulation of desires, and the false promise that happiness lies in acquisition, the commodities and careers that lure us on. More of everything, forever. One of the worst things capitalism can offer us is this promise of limitlessness. The lesson to be learned is that it is process, not product that we need.

When I go into the countryside to take photographs, the struggle with the equipment, the light, the weather and the composition are intrinsic to the experience itself. Failure and imperfection are part of it because they are part of me. Most trips lead to no usable images, because too many things can go wrong. It’s frustrating. But if my camera magically did all that for me, and took a perfect image every time, I would never bother to take another landscape photograph. The joy in it would be gone forever, because the joy is in the obstacles. Limits, not endless plenitude, are key to psychic health, an acceptance of the satisfaction in dissatisfaction. You can’t always get what you want, and that’s alright.

[1] See Byung-Chul Han’s Psychopolitics, or his The Burnout Society for the classic statement of this. In a different vocabulary and differing in key respects but with some similar concerns Todd McGowan’s Capitalism and Desire: The Psychic Cost of Free Markets, which is very insightful. Related studies are found in The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz and The High Price of Materialism by Tim Kasser.