by Mark Harvey

One of the artifacts of modern American culture is the digital clutter that crowds our minds and crowds our days. I’m old enough to have grown up in the era before even answering machines and the glorification of fast information. It’s an era that’s hard to remember because like most Americans, I’ve gotten lost in the sea of immediate “content” and the vast body of information at our fingertips and on our phones. While it’s a delicious feeling to be able to access almost every bit of knowledge acquired by humankind over the last few thousand years, I suspect the resulting mental clutter has in many ways made us just plain dumber. Our little brains can absorb and process a lot of information but digesting the massive amount of data available nowadays has some of our minds resembling the storage units of hoarders: an unholy mess of useless facts and impressions guarded in a dark space with a lost key.

If you consider who our “wise men” and “wise women” are these days, they sure seem dumber than men and women of past centuries. I guess some of them are incredibly clever when it comes to computers, material science, genetic engineering, and the like. But when it comes to big-picture thinking, even the most glorified billionaires just seem foolish. And our batch of politicians even more so.

It’s hard to know the shape and content of the human mind in our millions of years of development but the story goes that we’ve advanced in consciousness almost every century, with major advances in periods such as the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. That may be true for certain individuals but as a whole, it seems we drove right on past the bus stop of higher consciousness with our digital orgy and embryonic embrace of artificial intelligence. Are we losing the wonderful feeling, agency, and utility of uncluttered minds?

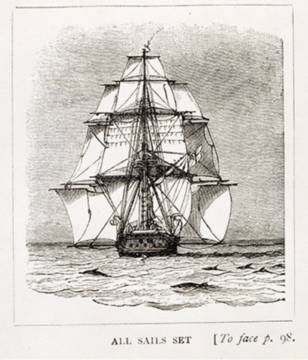

One of the greatest breakthroughs in our understanding of our place and evolution on this here earth came out of Charles Darwin’s journey first at sea and then churning his experiences over in his mind’s eye back at home in the Kent countryside just south of London. That five-year voyage covering some 40,000 miles on the Beagle is just not something that could possibly happen today. To begin, the captain of the Beagle, Robert Fitzroy, was only 26 years old, and Darwin was only 22. Show me a man or woman that young in today’s world that could navigate a sloop around the earth in those conditions, collect and catalog thousands of species of plants and animals, make thousands of keen observations and world-class sketches, and I’ll send you a new iPhone. Unfortunately, we’ve lost those skills, patience, and capacity of observation seen in a number of men and women of the 19th century.

It’s certainly no fault of our youth as they, like every generation, are carried along by the tides of the moment, and at this moment, those tides come in the form of really fast microprocessors, really fast Wi-Fi, and millions of ephemeral videos, photos, posts, texts, likes, and the like.

Darwin and Captain Fitzroy lived remarkable lives—unimaginable today. At the age of 12 Fitzroy was sent to the Royal Naval College in Portsmouth. The education there was rigorous and a student was meant to learn projectile science, calculus and its use in measuring surfaces and three-dimensional objects, mechanics, hydrostatics, astronomy, tidal movements, naval history, lunar effects on the tides, and more.

When he was 14, Fitzroy shipped off on a two-year voyage to South America on the Owen Glendower. Conditions at sea in those days were brutal as evidenced by the many descriptions of maggot-infested biscuits, salted beef that had been stored in casks for years, cabin quarters that housed men cheek by jowl, fetid water, and foul wine.

Given his youth at entering the naval college and his immediate experience of long voyages at sea at only age 14, by the time he was 26 and put in charge of the Beagle, he already had vast experience.

Darwin’s life journey was much more surreptitious and his voyage on the Beagle began with none of the import of his world-changing theories. Though he turned out to be a great naturalist, he was actually brought aboard the Beagle to be a companion and conversationalist to Fitzroy. Aware that the previous captain of the Beagle had committed suicide mid-voyage and that his own uncle had slit his own throat in a period of despond, Fitzroy took measures to preserve his sanity by bringing along a Cambridge-educated young man to keep him company. Fitzroy knew his own nature and had a terrible temper that earned him the nickname “Hot Coffee.” He figured it would help him on the long voyage to have a companion of his own level of education as the hands working the ship were generally uneducated and often illiterate.

Darwin’s life journey was much more surreptitious and his voyage on the Beagle began with none of the import of his world-changing theories. Though he turned out to be a great naturalist, he was actually brought aboard the Beagle to be a companion and conversationalist to Fitzroy. Aware that the previous captain of the Beagle had committed suicide mid-voyage and that his own uncle had slit his own throat in a period of despond, Fitzroy took measures to preserve his sanity by bringing along a Cambridge-educated young man to keep him company. Fitzroy knew his own nature and had a terrible temper that earned him the nickname “Hot Coffee.” He figured it would help him on the long voyage to have a companion of his own level of education as the hands working the ship were generally uneducated and often illiterate.

Darwin and Fitzroy mostly got along and became good friends. There were a few altercations and once Fitzroy banned Darwin from his company for a few hours when they argued over slavery. But Fitzroy quickly apologized and the two reconciled.

Tragically, later in life, Fitzroy cut his own throat. Impossible to perfectly diagnose his despond, but he did have some failures after the voyage of the Beagle. He had been made governor of New Zealand and became despised by white settlers there for his sympathy for the Mauri people, even pardoning a Mauri chief after he killed nine whites over land disagreements.

Reading Darwin’s account of the journey in The Voyage of the Beagle, one can’t be but in awe of his capacity of observation. Darwin’s first entry in The Voyage of the Beagle was about his visit to Cape Verde and one of his last entries was about the Azores on his way back to England. In the intervening hundreds of pages, the breadth and detail of what he observed is astounding. In a letter to his sister, Darwin wrote, “…there is nothing like geology; the pleasure of the first days partridge shooting or first days hunting cannot be compared to finding a fine group of fossil bones, which tell their story of former times with almost a living tongue.”

His observations along the five-year voyage are detailed and show a remarkable knowledge of flora, fauna, and geology. You could open up The Voyage of The Beagle almost anywhere and find entries like this:

The whole surface of the water, as it appeared under a weak lens, seemed as if covered by chopped bits of hay, with their ends jagged. One of the larger particles measured .03 of an inch in length, and .009 in breadth. Examined more carefully, each is seen to consist of from twenty to sixty cylindrical filaments, which have perfectly rounded extremities, and are divided at regular intervals by transverse septa, containing a brownish-green flocculent matter. The filaments must be enveloped in some viscid fluid, for the bundles adhered together without actual contact.

Besides being a great ship captain, Fitzroy was tremendously observant too. He acquired his own collection of species on the voyage of the Beagle and his collection of finches was superior to Darwin’s. In fact, Darwin turned to Fitzroy’s collection in trying to understand the variations seen on the Galapagos Islands. Fitzroy could also be considered the inventor of modern weather forecasting (he invented the term forecast) and created the first daily and nationwide weather service in England. To that end, he invented a very reliable and portable weather station and equipped outgoing ships with it to gather data about trade winds, storms, and weather patterns asea.

Darwin didn’t publish his theory of evolution in his book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection until about 20 years after his return on the Beagle. As a young man, he had originally intended to join the clergy in The Church of England and he rightfully feared the backlash his theory would cause in the church and even among naturalists. Some of the most accomplished naturalists of that era, such as the French scientist Georges Cuvier, rejected Darwin’s theory despite having studied and practically invented paleontology. Cuvier named several of today’s extinct species such as the Mastodon and the Pterodactylus, convinced the world that species actually do go extinct, and vastly expanded the taxonomy of invertebrates. But he still didn’t believe Darwin’s ideas on transmutation and evolution.

And Darwin was harshly pilloried by the Church and cartoonists of the time never got tired of depicting him as half ape or swinging from a tree.

While the sea-going voyages of Fitzroy and Darwin probably shouldn’t be too romanticized (as they were brutal and often deadly affairs), one can’t help but envy both men’s prodigious skills, powers of observation, and, yes, uncluttered minds. I think in the days before our digital orgy we were forced into more meditative states. The men and women riding thirty miles a day on a horse in our pioneering era had to have been rocked into a meditative state on some of their journeys. Sailors on long journeys between hoisting a sail or swabbing a deck (with no wifi or earbuds) must have had periods of trance and contemplation with the sounds of the ocean and the gulls.

Today the individual mind and the collective mind are piecemeal and fragmented by a thousand texts and emails, a million images–each of whose meaning lasts about three seconds–and a resulting inability for long-term observation. It’s not to say that there wasn’t plenty of foolishness and fundamentalism in earlier days, but I’m not sure it can rival the foolishness and shrill qualities of today’s leaders. Watching a bleating politician on television or the orgiastic showmanship of some of our billionaires, one has to conclude that they would all improve their thinking and judgment by spending five years on the Beagle studying finches, lizards, and cephalopods. Loaded with some of these blow-hardy fools, one might hope the Beagle would never return.