Alison Abbott in Nature:

Graça Raposo was a young postdoc in the Netherlands in 1996 when she discovered that cells in her laboratory were sending secret messages to each other. She was exploring how immune cells react to foreign molecules. Using electron microscopy, she saw how cells ingested these molecules, which became stuck to the surface of tiny intracellular vesicles. The cells then spat out the vesicles, along with the foreign cargo, and Raposo captured them. Next, she presented them to another type of immune cell. It reacted to the package just as it would to a foreign molecule1.

Graça Raposo was a young postdoc in the Netherlands in 1996 when she discovered that cells in her laboratory were sending secret messages to each other. She was exploring how immune cells react to foreign molecules. Using electron microscopy, she saw how cells ingested these molecules, which became stuck to the surface of tiny intracellular vesicles. The cells then spat out the vesicles, along with the foreign cargo, and Raposo captured them. Next, she presented them to another type of immune cell. It reacted to the package just as it would to a foreign molecule1.

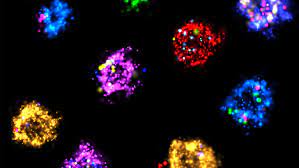

It was a demonstration that these extracellular vesicles (EVs, also known as exosomes) might be transmitting information between cells. “We knew that exosomes existed, but at that time they were generally thought to be a way of getting rid of a cell’s trash,” says Raposo. “It was exciting to find that some could have important biological functions — even if not everyone believed it at first.” Just two years later, together with her colleagues, Raposo, who is now at the Curie Institute in Paris, found that exosomes derived from antitumour immune cells could be enlisted to suppress cancers in mice2.

Other scientists jumped on the concept, and began to find exosomes being spat out from all kinds of cell. Interest exploded after researchers discovered that the little packages could contain not only proteins, but also nucleic acids. In 2007, for instance, a Swedish team found that the vesicles harboured small RNA molecules3. That implied that exosomes might influence gene expression when they reached their destination cells. The number of EV-related publications rose steeply, and has tripled in the past five years.

More here.