by Michael Liss

Some Presidencies just come apart: The men occupying the office are objectively unable to manage the chaos around them. Herbert Hoover’s might be thought of as in this category. James Buchanan’s as well. Perhaps Jimmy Carter’s. Others, like Richard Nixon’s, die of self-harm, unmourned. Still others end in “fatigue”—their party, or the public, essentially tires of them. Harry Truman’s flirtation with running for a second full term fell victim to Estes Kefauver, Adlai Stevenson, and a mostly uninterested Democratic Establishment. George Herbert Walker Bush found “Message: I care” not quite as compelling as he had hoped. Sometimes the public, or just the Party, wants a change.

What separates the survivors, the people who seek and succeed both at the job itself and the politics of getting reelected? It’s certainly not being free of the seven deadly sins. Nor is it being above politics. It’s a core philosophical anomaly of our system that our Chief Executive is charged with acting on behalf of all citizens while being the political leader of half. That takes, along with the talent, intelligence, and temperament to get the job done, a certain moral agility, a selective application of standards of right and wrong, sometimes even to the extent of muting the dictates of conscience. Presidents are in the business of making choices, often ones where there are shades of grey rather than clear bright lines, and, to make these choices, they have to call upon their own resources, both light and dark.

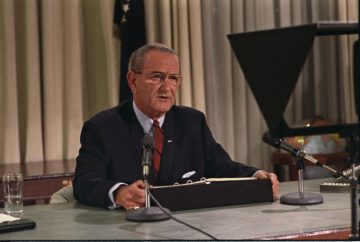

If you could somehow take samples of DNA from every President, good, bad and indifferent, and run them through a centrifuge, you might, might come up with a sample that resembles Lyndon Baines Johnson. A complex, contradictory man with a complex and contradictory record.

Any fair evaluation of LBJ’s Presidency must include the tragedy that preceded it. For slightly over two hours on November 22, 1963, until the fatally wounded JFK succumbed and Johnson could take the Oath of Office, the country was an orphan, without a President. An unfillable hole had been created, patched over by the Constitutional process for succession, but emotionally unsatisfying. The public didn’t dislike LBJ, but it had not asked for him. It chose Kennedy, and he had then been ripped from its arms.

Still, the machinery of peaceful succession moved on, as it must. America can pause to remember, but one person is not a government, and our citizens have lives to live. Johnson started strongly. He handled the “mourner-in-chief” role well, showed tact and sensitivity in dealing with the grieving family and the grieving nation. He used his considerable legislative gifts to lever JFK’s legacy into an impetus for groundbreaking social and civil rights legislation—taking significant political risks to do so. He appointed high-level committees to look at seemingly intractable problems plaguing America and to suggest solutions. He didn’t just ponder, he acted: In his Great Society initiatives, he laid out a broad vision with an updated approach to the New Deal. The Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, Medicare, and Medicaid were all products of his efforts. For all the potential controversy of what he was doing, his approval ratings were stunning—sustained in the 70s all through 1964 (including the period of his crushing landslide over Barry Goldwater) and in the mid-60s through 1965. This is part of the LBJ legacy, and it is an impressive one.

Even with all these accomplishments, LBJ still had two backbreaking problems. Domestically, legislation and study couldn’t change enough minds, suggest enough innovations, or improve conditions enough to deal with racial problems. That the racial divide wasn’t new didn’t make it less of an issue. The expectations of the Black community after World War II just had not been met; its patience was exhausted, while, at the same time, white backlash was rising. LBJ fought mightily, even heroically, against this, but he fell short. Perhaps no one could have done better, but what was done was both way too much for some, and not nearly enough for others.

Pain at home, more abroad. Vietnam was LBJ’s most stupendous unforced error. Let’s be fair and say American involvement in Vietnam was a legacy inherited from both Eisenhower and JFK. We can acknowledge that, while stating the facts: the American troop involvement in 1963 was 16,300, and it grew to just 23,300 in 1964. Once reelected, LBJ went at it with a determination that shocked the country. Using enhanced Presidential power granted him with Congress’s adoption of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, American men, volunteer and conscripted, were poured into Vietnam. Troop levels reached 84,300 in 1965 and 385,300 in 1966. The public reacted, and Democrats lost 47 House seats in the Midterms. LBJ was not deterred. 485,600 in 1967. Along with seemingly endless troop escalations came the bombing campaign known as Operation Rolling Thunder, which began in March of 1965 and did not end until November of 1968.

Why? Hindsight is easy. We know that JFK’s Cabinet was hawkish, and LBJ kept on key members. We know that most of the military voices that LBJ heard were optimistic to the point of being Pollyannaish. It was always one more push, 50,000 more men, more and different weaponry, expanded bombing targets, and better training of ARVN—but we were winning the war and constantly degrading the enemy’s military capabilities. Johnson was stubborn; he believed in the Domino Theory; he was convinced American victory was essential; and he sought it single-mindedly.

The problem was that the glacial hand of reality was knocking at the door. The draft kept taking boys from their homes, and too many came back maimed or in boxes. In 1967, roughly 1000 men a month were lost, and many times that wounded. On Vietnam, the public was splitting along cultural lines, with colleges being centers of resistance and blue-collar workers more supportive. Increasingly, the war-skeptical public saw itself without a real choice—either vote LBJ, and a continuation and perhaps escalation of American involvement, or vote Republican, and end up with the same policy options. The anti-war movement needed leadership—not just at the grassroots, but near the top. It needed a champion with, or having the potential to create, a national profile. All through the fall of 1967, activist Democrats, particularly Allard Lowenstein, but also a variety of leaders of student groups from across the country, began seeking out a candidate—and getting turned down. Vietnam was not easy. Some of the anti-war Senators who might have led were concerned about keeping their own seats, others didn’t think the time was quite right (or ever right) to take on a sitting President of their own party. Robert Kennedy was in the latter group. They asked; he said no. Finally, they found one in Minnesota’s “less famous” Senator, Eugene McCarthy. No more LBJ against a GOP rival. Now LBJ or McCarthy against a GOP rival.

It is hard to describe McCarthy. Perhaps Hubert Humphrey nailed it when he said, “Basically, Gene disdains whatever peer group he is in.” McCarthy managed an Olympian remoteness that seemed almost Zen-like. He sometimes gave off the impression that politics was beneath him. He wasn’t hands-on in his campaign. His public statements were airy, educated, sometimes above his audience—and he liked it that way. It’s almost easier to describe what he wasn’t—not dynamic, not particularly charismatic, not (not) a round-the-clock worker. Still, after much self-absorbed pondering, he allowed himself, in a Garbo-like way, to announce he’d be entering the New Hampshire Primary. He was going to take on LBJ. That was news.

McCarthy’s candidacy was not at all quixotic: First, his core staff really did have talent, and they focused it on college campuses and amongst the young. There’s a tendency to see the McCarthy team as having been staffed by men with beads and beards, and barefoot women in tie-dye. Those people were part of the movement, but equally important was the tremendously energetic contingent of those who wouldn’t have looked out of place at a training meeting at IBM. McCarthy also possessed a genuine aversion to the war that did not seem at all synthetic, and a personal beef with LBJ to keep the home fires warm. In 1964, LBJ had told both McCarthy and Minnesota’s then Senior Senator (a gentleman named Hubert Horatio Humphrey) that one of the two of them would be his Veep. McCarthy didn’t like the manipulation and pulled out just in time…to hear LBJ to pick Hubert. The incident created some bad blood between McCarthy and LBJ.

Now that there were two, could there be more? Yes, because Robert F. Kennedy hung over the field (and particularly over LBJ). It’s not that Bobby hadn’t thought about it. He had. It’s not that he wasn’t getting a lot of advice from his extended Kennedy brain trust, the “old guys” from JFK’s time and some of the “Young Turks.” He was. It’s not like he didn’t want the job—he was, after all, a Kennedy, just as ambitious, just as tough, and maybe more ruthless than the others. But Kennedys play to win, and RFK had a lot of concerns about how it would look if a Kennedy challenged any Democratic President, and perhaps especially LBJ. His brain trust split—all agreed it was inevitable he would run for the Presidency. But was 1968 too soon? Teddy thought it was. Or 1972 too late, as many of the others suggested.

Kennedy continued to grapple with it. In late 1967, as McCarthy was getting in, Kennedy was telling people he wouldn’t accept a draft. He maintained that position through January, despite McCarthy’s gearing up and Johnson’s continuing to escalate in Vietnam. On January 31, 1968, he met with a large number of political journalists at the National Press Club. The rules of engagement were that everything was off the record, on “background only” unless specifically permitted by RFK to be on. The atmosphere was supposed to induce frankness, and Bobby was frank—on most things. He critiqued Vietnam as “one of the great disasters of all time,” but seriously questioned McCarthy’s approach to campaigning for his apparent disinterest in the problems of race and the inner cities. Bobby felt both were moral crusades, and McCarthy’s one-issue focus had, in effect, diminished those other issues. The journalists certainly loved the inside dirt, but what they really wanted to know was whether Bobby was sticking to his guns or would join LBJ and McCarthy and duke it out for the Presidency. Kennedy was still out, still (at least publicly) concerned about splitting his Party and ceding the Oval Office to the Republicans. The boys on the bus wanted more than this, so Bobby allowed (for public consumption) that he would not enter the campaign under “any foreseeable circumstances.”

What Bobby did not know was that, at that very moment, the unforeseeable was in the process of becoming reality. Reporters with him began to see wire reports about a new, comprehensive military assault by the North Vietnamese against South Vietnamese cities and military assets. What became known as the Tet Offensive had just begun, and it was about to change history.

What Americans learned from Tet, most impactfully from that first phase (the entire operation ended September 23) was that, contrary to the rosy evaluations from the military and President Johnson, the North Vietnamese weren’t going quietly into the night. In fact, they literally penetrated the outer wall of the US Embassy in Saigon before being turned. This was not an enemy on its heels.

Tet also helped set in motion a domestic figure with the potential to change minds, Walter Cronkite. Cronkite was the most respected man in television journalism, and although, up to that point, he had been generally Establishment-neutral, he decided he needed to see for himself. On February 6th, he took a small crew with him on a 19-day trip through the war zone, seeing things firsthand, talking to as many people as he could, getting away from the cocoon in which General Westmoreland tried to keep him. He took personal risks, at one point needing to be evacuated from the smoldering city of Hue on a helicopter also carrying 12 body bags. When he returned to the States, he and his team meticulously assembled a show, aired on February 27, 1968, that was just devastating to the Administration’s position.

He closed with this:

But it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy and did the best they could. This is Walter Cronkite. Good night.

Johnson, upon hearing these words, knew that something had irrevocably changed, reputedly saying, “If I’ve lost Cronkite than I’ve lost Middle America.” What’s more, Cronkite made it impossible to argue that the only “peaceniks” were silly students and flaky eggheads. Cronkite’s gravitas enhanced the movement’s seriousness.

Still, Bobby stayed out, despite the increasing pressure from his closest advisors, some of whom were ready to go work for McCarthy.

March 12, 1968, the almost unthinkable almost happened. The incumbent President of the United States, albeit running only as a write-in, was nearly defeated by Eugene McCarthy, a man with a shaggy-dog operation who, only a month before, had reported fundraising just one quarter of what was budgeted. Johnson was shocked and wounded. While he still controlled the party apparatus (and we were still in an era where primaries were largely for show), he’d been embarrassed. What’s more, the result weakened Johnson’s hand in the things he cared about. First, he was already having trouble getting what he considered vital legislation through an increasingly resistant Congress—not the thing a former Master of the Senate was used to. Second, eroding American support for the war weakened him, while he still clung to the hope that a major American commitment plus relentless bombing would achieve a form of victory. Johnson still had the power—not just of the Presidency, but also specifically granted to him in the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution—but what he was losing was the moral authority.

Tet, Cronkite, New Hampshire, and then the dam broke. There really were three candidates. On March 16, Robert F. Kennedy formally declared, infuriating McCarthy, and deeply unsettling LBJ. What was McCarthy all up in arms about? After all, no one, not even a man with as healthy a sense of self as Eugene McCarthy, was entitled to the nomination. But Bobby had said no the previous fall, he’d said no again on January 31st—and now, having taken no risks at all, he was trying to go through the palace gates knocked open by McCarthy himself. As for LBJ, the bizarre psychodrama between him and RFK had roots in real grievances. LBJ hated losing, period, but Bobby was almost certainly right that Johnson “feared” losing to him.

What neither McCarthy nor RFK could have had any substantive knowledge of (although Kennedy had guessed at it months before) was that the confluence of events really was preying on Johnson’s mind. LBJ had always possessed a sense of destiny, but he was also fatalistic. Johnson men did not live long lives, and he was approaching his complement. In 1955, he’d had a serious heart attack and had given up smoking and his favorite foods as a result. There was no question that the stress on the job was wearing on him…he was looking considerably older. He wondered, as well, about his political longevity. He could read polls, and Gallup’s mid-March numbers were the worst to date of his Presidency. So, very gradually, sliding back and forth from stubbornness, to exhaustion, to frustration, and perhaps even feeling a sense of martyrdom, he was convincing himself that he’d have a far greater chance of achieving his military and legislative goals if he simply announced he wasn’t running for a second term. With all that would come the added benefit of appearing statesman-like and self-sacrificing.

Inside the LBJ inner circle, which included his wife and his two daughters, both of whom were married to soldiers headed to Vietnam, the choices were less clear. Many of his closest political advisors were aware of a basic law of American politics—it’s a lot easier for a lame duck to quack than it is to walk. What Johnson really wanted was a second term without the peskiness (or malevolence) of some of his own party’s most inflated egos nipping at him. Then, he could finish Vietnam on his own terms and press for the Great Society programs on which he had not yet been able to deliver.

Johnson still thought he could win. He still had the unions when the unions were key sources of cash and infrastructure for any Democrat—and some of those union heads absolutely hated Bobby because of his crusade against corruption in the Teamsters when he was Chief Counsel to the Senate’s Rackets Committee in the later 1950s. He also still had the support of the old party bosses, like Richard Daley, running the old party machines. Finally, and possibly decisively, he had the old system for the unions and party bosses to manipulate. One of the less understood aspects of Presidential nominations pre-1968 is that many of the primaries didn’t conclusively select the nominees, the bosses did. The slate of delegates from a state might go unpledged, or pledged only on the first round, or dominated by a “Favorite Son” candidate there to swap favors.

What may have tipped Johnson was the realization that the Democratic coalition was eroding faster than expected. Southern Democrats, who would support him on Vietnam, were upset about his domestic program, particularly on Civil Rights. Many would defect to George Wallace. And more progressive, younger, more urban voters who agreed with his Great Society push completely rejected his policies on Vietnam. He might very well get the nomination with the help of his institutional constituency. He might also beat the eventual Republican nominee. But he might also suffer more defeats, demonstrate clearly that he had lost the ear of the Democratic voter, and blow up the balance of his domestic accomplishments while doing nothing positive in Vietnam.

It late March, he announced he’d be delivering a major speech on March 31 on his war (and peace) policy in Vietnam. He did not tip his hand on the substance of that speech. Nor did he mention his second intention, not fully formed, not totally agreed on, not in any way final, that, whoever the country’s next President might be, it would not be Lyndon Baines Johnson, and he would say so. There was more debate among his advisors and family. Finally, he made up his mind, and his Vietnam speech and the political addendum were loaded into the teleprompter. Cameras on, he delivered the “military” aspect, including a long-sought cessation of the bombing except in very narrowly defined areas. He urged Americans to support his policies, and the North Vietnamese to come to the bargaining table. Then, a deep breath, and “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.”

A stunned nation stopped what it was doing. For the briefest moment in time, Johnson got the honeymoon he wanted. The press sang his praises: the public approved. Everyone knew the field would go back to three when LBJ’s Vice President (and presumed heir to the traditional labor and party boss assets) announced, but for now, Humphrey just wept. McCarthy and Kennedy were subdued and gracious in public.

The sunshine held for exactly four days. On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King stepped out on the balcony of his room at the Lorraine Motel, Memphis, Tennessee. He was there to join in a march that was to be held the following Monday in support of Memphis’s Sanitation workers strike. He didn’t make it. At 6:05 p.m., he was struck in the face by an assassin’s bullet. Rushed to a nearby hospital, he was soon declared dead.

As if Vietnam was not enough, one hundred cities now exploded in agony and in rage.

Coming in September: The aftermath of King, Humphrey formally in, RFK and McCarthy slug it out, Wisconsin, Oregon, California, the tragedy at the Ambassador Hotel, McGovern in, chaos in Chicago, Nixon, Wallace, and Humphrey’s last dash for the crown.