by Akim Reinhardt

Former NFL wide receiver Henry Ruggs III was recently sentenced to 3–10 years for a drunk driving accident that killed 23-year-old Tina Tintor and her dog. Ruggs had a blood alcohol level of 0.18 (>2x legal limit) and was driving his Corvette 156 mph when he struck her vehicle. Tintor’s Toyota caught fire and firefighters were unable to free her. She died inside the flaming wreckage.

Before the sentencing, Ruggs read a statement on the courthouse steps:

“I sincerely apologize for my actions the morning of Nov. 2, 2021. My actions are not a true reflection of me.”

But what, exactly, is a “me,” and to what degree can actions reflect it?

For centuries, a longstanding Christian theological debate has centered on the importance of faith vs. actions (or “works”). Generally speaking and in very simplified terms, Catholicism teaches that faith is paramount, and any immoral action (sin) can be forgiven through the Church if one believes, while various Protestant denominations emphasize how good acts reflect a devotion to God. Sometimes I think of it as Descartes’ Cogito ergo sum (“I think, therefor I am”) vs. singer/songwriter Jim Croce’s:

After all it’s what we’ve done

That makes us what we are.

However, I’m a historian, not a theologian. When it comes to defining a person, I don’t see actions and ideas in such tension with each other. Nor do I see them dominating the debate to the exclusion of other factors. Rather, my understanding of “me” or “you” is temporally based. It is dynamic. I focus on the complex equation of continuity and change over time.

People maintain and express consistencies. However, very few, if any, run through a person’s entire lifetime. People change. People are always changing.

The changes in someone’s capacities and personality are so wild and radical during childhood that most religions exempt them from moral culpability up to a certain point. As life progresses, most changes become slow and uneven. So slow by adulthood that they can be difficult to perceive, creating an illusion of relative stasis, like the mountain that seems eternal despite the radical tectonic processes that formed it, and the relentless, grinding erosion that will eventually tear it down.

Other changes, particularly when they are unwelcome, can be sudden and impossible to ignore. For example, hair loss and eventual impotence for men, and the array of changes that come with female menopause. Beyond the physical, our personalities continue changing as well. We are always learning, whether we consciously try to or not, absorbing new information, assessing new situations, and even evolving what seem like fundamental ideas. Listening to traditional “Conservative” Republicans explain their support for Donald Trump in 2016 is a recent example of how millions of people shifted an element of their belief systems, even if they refused to acknowledge they were doing so.

At the same time, a person can go from cradle to grave with certain bedrock values and ideas. A belief in God. A sense of right and wrong about some specific thing(s). A love of a pet or friend or family member. And of course a profound ignorance of most things in the world. For what we know and do is always complemented by what we do not know and do not do.

A historian can spend a lifetime trying to understand the nature of these transformations and consistencies, the elusive relationship between continuity and change for individuals as well as the families, communities, cultures, and societies they create.

For centuries, those who studied the past often emphasized the importance of change, especially big changes. Revolutions. Wars. The rise and fall of civilizations. The power of a “great man” to enforce his will upon those around him and change the world. Then in the early to mid-20th century, French Historians of the Annales School, particularly Fernand Braudel, popularized the idea of the longue durée. In understanding history, they asserted that moments of great change are not so important as the long consistencies that stretch over vast periods of time. Our eyes might be drawn to the dramatic flair of fireflies flashing, but the black velvet of the nighttime sky is more important, enduring, influential, and ultimately more revealing in its own way.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, a new generation of historians sought to reconstruct the histories of “subalterns”: the vast masses of people, the poor and exploited, the subjugated and conquered, who had been purposefully ignored and/or unable to leave records behind. Historians worked to recover their voices and showcase their long-erased agency, to reveal how they viewed the world and engaged change as they struggled against oppressive forces and strove for some semblance of power and/or equality.

Nowadays structure is making a comeback. Big abstract forces, such as Capitalism and Colonialism, are popular areas of study among historians and theoreticians. My own work examines a specific brand of colonialism: settler colonialism. However, most of today’s historians are not trying to simply swing the pendulum away from agency and back to structure. Forces like capitalism and colonialism may be systemic, but individuals maintain agency; they can and do react in a variety of ways. Structures may engineer and foment change, but they also create consistencies. And while structural forces are inescapable, individuals aren’t completely trapped by them; they can and do resist, collectively influence them, and even escape them in some ways. Today we seek to understand both structure and agency, and the subtle interplays between them.

Individuals maintain a self, and their agency is real. Yet it is also limited, sometimes severely, by structural forces that are also very real, if abstract.

Meanwhile, over in neuroscience, as best I can tell, they are directly challenging the very notion of the self. Your corpus exists, of course. But it’s not so simple as receiving sensory information that allows your brain to make executive decisions. Your brain also invents narratives around the information it receives. Inventing those narratives seems to be an automatic process. Turning it off is so difficult that people spend years mastering meditation so they can achieve a few quiet waking moments without narratives. What’s more, those narratives can be very wrong. In fact, scientific studies show that human brains will construct narratives even in the absence of necessary information. Without sufficient evidence to explain a situation, we just make shit up. Indeed, there is increasing evidence that individual agency may be an illusion. The brain may not actually be a “CEO” making decisions, but rather simply makes up stories that may or may not align with the sensory information it receives.

Meanwhile, over in neuroscience, as best I can tell, they are directly challenging the very notion of the self. Your corpus exists, of course. But it’s not so simple as receiving sensory information that allows your brain to make executive decisions. Your brain also invents narratives around the information it receives. Inventing those narratives seems to be an automatic process. Turning it off is so difficult that people spend years mastering meditation so they can achieve a few quiet waking moments without narratives. What’s more, those narratives can be very wrong. In fact, scientific studies show that human brains will construct narratives even in the absence of necessary information. Without sufficient evidence to explain a situation, we just make shit up. Indeed, there is increasing evidence that individual agency may be an illusion. The brain may not actually be a “CEO” making decisions, but rather simply makes up stories that may or may not align with the sensory information it receives.

People will believe any old goddamned thing. After more than half-a-century on this planet, that I do not doubt. However, barring firmer scientific evidence, I’m not yet ready to completely set aside agency and accept that we’re nothing more than a fleshy version of the robots we increasingly fear will replace us with the rise of Artificial Intelligence. After all, I did write this essay. And while the odds are minuscule, this thing I wrote might change your life (or mine), just a teensy-weesy bit. So Until they can prove otherwise (and I am open to such proofs), I will presume some degree of agency and assume the accompanying responsibilities.

I don’t know who the “true” Henry Ruggs III is today, or was on that night when he crashed his Corvette into Tina Tintor’s SUV. And I certainly have no idea whether he should be forgiven, or what afterlife might await him based on his actions and/or beliefs.

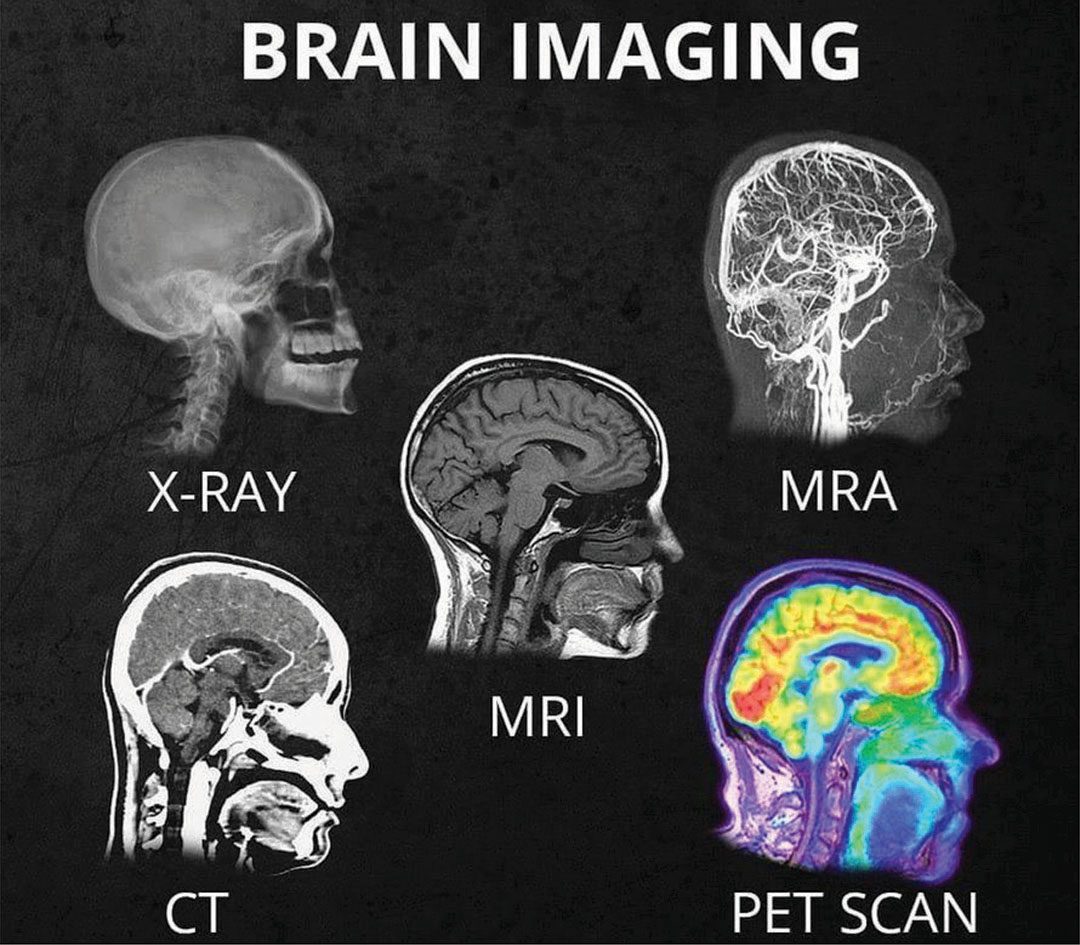

I do know that at the age of 22, his brain’s frontal cortex, which is involved in decision making and gauging risk and consequence, was not yet fully developed. I don’t know if that matters. I also don’t know if our punitive/retributive system of justice is the best system compared to others such as compensatory justice, restorative justice, and/or rehabilitation.

Should he be put in a cage for years? Perhaps he forfeited his right to be in our society. Should he give something(s) to her family that tries to make it right? As a professional football player, he was in a rare position to do so. Should he engage in a long and difficult process of redemption so as to bring their lives and society back into balance? If they were not a cynical attempt to manipulate the judge before sentencing (that’s a big IF), his recent words could have been the nascent beginnings of such process. Should he get serious mental health treatment so he can improve his self and better avoid doing horrible things in the future? Almost certainly, though the U.S. justice system largely gave up on rehabilitation decades ago, paying only lip service to it while focusing on discipline, surveillance, and punishment.

Should it be some combination of all these things? Possibly.

Who was he? Who is he? What is justice? I want to make up stories that might help provide answers. But sometimes the best thing to say, though it may be the hardest, is: I don’t know.

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com