by Rafaël Newman

On two separate occasions in mid-February this year, the Swiss parliament, or Bundeshaus, and adjoining ministry buildings in Bern had to be evacuated and searched following bomb threats. During the first incident, in which a lone man in military dress attempting to clear security at the parliament was apprehended when traces of explosive material were found on his person, locals were uncannily reminded of a text by the late, great Bernese singer-songwriter Mani Matter (1936-1972). In “Dynamit,” written over half a century ago, Matter tells of his daring intervention upon realizing that the bearded man he has met outside the Bundeshaus plans to blow up the building, because he is “for anarchy”:

What other choice did I have as a burgher

Than to attempt to dissuade him?—I spoke

As well as I could of our state’s many plusses:

The Rütli and freedom, democracy too;

I mentioned them all, and I begged him to stop.

Matter’s panic, he claims, lent a special force to his oratory (“The Swiss independence address I delivered / Would have made horses stand and salute”), and he is ultimately successful in talking down the would-be terrorist. That night in bed, however, having awarded himself a private medal for heroism, Matter has second thoughts:

Was it correct to praise Switzerland thus,

That is a question I ask to this day.

And if there’s one thing I learned from that fellow,

I walk by the place and I think of it still:

It’s only a matter of time, and explosives,

To blow the whole Bundeshaus into the sky.

In the course of one brief cabaret number—a recording of its live performance lasts barely two minutes—Matter conjures up the twin, opposing poles of the Swiss political consciousness: its conservative attachment to patriotism and traditional values (freedom, democracy) and its anarchist (or at least libertarian), anti-institutional streak.

These apparently contradictory strains are both crystallized in “the Rütli,” one of Matter’s sentimental touchpoints in his negotiation with the imaginary bomber: the meadow in central Switzerland where representatives of the cantons of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwald are popularly believed to have sworn their legendary oath (or Eid) in 1291, founding the Swiss confederation (or Eidgenossenschaft) in a revolt against tyrannical local representatives of the Holy Roman Empire. The Rütli, which was consecrated as a place of traditional Swiss patriotism in the mid-19th century, amidst romantic-historicist nostalgia following the establishment of modern, constitutional Switzerland in 1848, has more recently been notorious for gatherings of Swiss neo-Nazis, and for its own terrorist attack in 2007. It is thus a site invested with the spirit of both harmonious unity and violent revolt, an ostensibly tranquil lieu de mémoire located in the bucolic heart of primitive Switzerland from which early modern colonial aspirations have nevertheless radiated (since certain of today’s confederated cantons began life as vassal territories of the “original” nucleus of states), as well as a place to which centripetal, modern nation-building forces are drawn, in annual patriotic ceremonies of unity and common purpose.

By chance, the same week in which the government buildings in Bern were under attack this February (significantly carried out by lone terrorists, as opposed to the recent mass anti-democratic insurgencies in Washington, DC and Brasilia) also saw a production of Wilhelm Tell, Friedrich Schiller’s 1804 canonization of the ur-myth of Swiss independence, at the Schauspielhaus in Zurich. The city’s premiere theater had risen to prominence in the 1930s as a place of refuge for artists fleeing the Third Reich, who helped it become a venue for anti-fascist drama; it is currently under the leadership of a new team of German expats, Nicolas Stemann and Benjamin von Blomberg, whose stated aim, when they took over artistic direction in 2019, was to promote “diversity and inclusion, sustainability, and the expansion of the concept of theater.” (Stemann and von Blomberg’s contract, however, has not been renewed for a further season, as audience numbers have been declining and productions have been criticized in rightwing circles for their excessive “wokeness”.) And the current production of Wilhelm Tell, in fact a revival from last season’s program, is the work of Milo Rau, the activist Swiss-born artistic director of NTGent in Belgium, whose “Ghent Manifesto,” published upon his appointment in 2018, begins with an explicit evocation of Marx—“It’s not just about portraying the world anymore. It’s about changing it” —and includes a prohibition against “the literal adaptation of classics on stage”.

Under such auspices, then, it comes as no surprise that Rau’s Wilhelm Tell at the Schauspielhaus takes the ambivalence sketched in Mani Matter’s two-minute encounter with Swiss iconography and expands it into a two-hour critique of the current state of the Helvetian project. Central to Schiller’s classical drama, and to the Swiss foundation narrative it deploys, is the eponymous figure of Wilhelm Tell, known to opera fans as “Guillaume Tell” thanks to Rossini’s musical adaptation with the iconic overture. Rau’s Tell, as befits the postmodern staging of this mythical character (borrowed for Swiss “history” from Nordic saga), is refracted into various members of the ensemble cast, which is composed, in keeping with Rau’s Manifesto, of amateur as well as professional actors: a Swiss-Jewish, female army officer; a bearded drug enforcement agent and hobby hunter from rural Switzerland; a young mother and book illustrator with phocomeliac limbs; a Swiss geriatric nurse and person of color; an Eritrean refugee living “illegally” in Switzerland; a wheelchair-bound activist for the rights of the differently abled. This is done, in addition to retelling and reshaping the mythologized history, with an eye to thematizing a host of ills besetting contemporary Switzerland, as incorporated in, or symbolized by, the specific physical presences of the actors: ills such as racial profiling and police brutality; the precarious situation of sans-papiers in a climate generally hostile to immigration; the display of artworks “purchased” from Jews fleeing the Third Reich; or the existence of indentured servitude in postwar Switzerland.

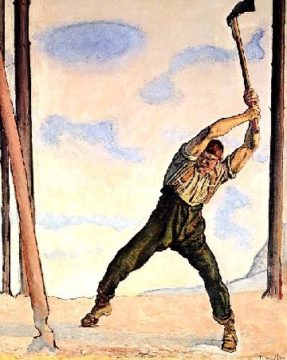

There is of course a deliberate irony in this collectivization of the central character in Schiller’s drama. For the German playwright bequeathed to Switzerland a Tell who is anything but a man of the people: Schiller’s eponymous protagonist is a sort of medieval superhero, a lone-wolf survivalist whose personal vendetta against the sadistic viceroy Gessler triggers the Swiss uprising he is himself reluctant to join. Schiller has Tell espouse rugged self-reliance and asceticism in aphoristic lines that have become proverbial, akin to the integration of Shakespeare into common English parlance, cited here in the slightly antiquated, 19th-century standard English translation of Theodore Martin: “The strong man is the strongest when alone,” “A true-born archer helps himself,” “Early practice only makes the master,” and “The axe at home oft saves the carpenter.” This last—Die Axt im Haus erspart den Zimmermann, which might also be rendered “An ax a day keeps the builders away”—is emblematic of the Swiss nexus of tradition and anarchism evoked in Matter’s “Dynamit”: the same homely tool that fashions the resources necessary for accommodation can also be used as a weapon of destruction, to avert the foe, imperialist or otherwise, and to forestall the rise of all-too centralized or communalist social constructions.

The closing scene of Schiller’s drama stages these opposing forces together, as a wedding is celebrated between members of the “international” nobility (Bertha von Bruneck and Ulrich von Rudenz), now committed to the “people’s” cause of Swiss independence, while a prison fortress erected by the tyrannical Habsburgs is dismantled. Attachment to the traditional value of marital union is thereby juxtaposed with a revolutionary will to tear down the institutions of centralized control. Rau cleverly “updates” these gestures, drawing them out of their Schillerian context—that of a nascent Switzerland struggling with foreign overlords—to turn the spotlight on two internal Swiss contradictions: the precarious status of asylum seekers in “humanitarian” Switzerland, and the staunchly upright country’s inglorious history as a hub for artworks of unethical provenance. Rau is known for mingling dramatic spectacle with real-life political action: in productions set amongst migrant workers in Italy or thematizing corporate malfeasance in Congo, he has also managed to effect actual social and legal change. For his Tell Rau stages a “performative” event beyond the scope of the proscenium but presented to the live audience in video form, a mariage blanc between two members of the ensemble, Hermon Habtemariam, the Eritrean asylum-seeker, and Sarah Brunner, the Swiss-Jewish army officer, making of the former a newly minted bearer of Swiss residency papers. In another related action, not integrated into the theatrical performance but included in the publicity campaign for his play, Rau hires a shaman to purge the nearby Kunsthaus Zürich of contamination by its recent acquisition of the Bührle Collection now displayed in its opulent new wing. This significant assortment of French Impressionist and other major works of modern art is on permanent loan from the estate of Emil Bührle, the German industrialist who sold arms to Nazi Germany from his home in Switzerland, and then used the proceeds to accrue his collection at bargain prices from Jews fleeing the Third Reich. The museum’s extensive (and expensive) new wing was built over the past decade to house the collection, part of a much-criticized plan by Zurich’s Socialist-Green coalition government to upgrade the city’s standing as an international destination for business and cultural tourism.

The Bührle controversy, which continues to divide Zurich along unexpected political lines, also furnishes Rau’s Tell with its most stirring scene. Standing at a pulpit erected mid-stage and surrounded in a semi-circle by the rest of the ensemble at a respectful distance, Irma Frei, now over eighty, recounts her real-life experience as a forced laborer in the 1960s, working for years as a teenager at a textile factory owned by Bührle for a final “wage” of 50 francs when she was released from semi-bondage at the age of 20. Having been constrained, as a “wayward” young woman, to a life spent between a loveless shelter and relentless shiftwork, prevented from seeing or corresponding with her family, and without a word of apology from the Bührle family to this day, Frei nevertheless manages a serene dignity. Meanwhile, her calm and her folksy diction contrast well with the explosive energy of another “action” aimed at the Kunsthaus and its tainted collection, only half incorporated into the drama. The rudimentary church that occupies center stage at the Schauspielhaus, representing medieval Altdorf, Tell’s legendary home village, is festooned with the anachronistic slogan HÄNGT DEN BÜHRLE AN EIN SCHNÜRLE—“Hang Bührle by the neck”. This implied violence is also communicated in a video interview made available to the media prior to the play’s opening, when Rau meets the Swiss-Jewish artist Miriam Cahn, whose works also hang in the Kunsthaus and who has tried in vain to have them removed in protest since the arrival of the arms manufacturer’s ill-gotten art collection. Rau’s inclusion of details from Cahn’s often grotesquely savage portraits in his production serves, then, as their symbolic “release” from imprisonment in the modern fortress of a cultural institution tacitly complicit with crimes against humanity.

In this way, Rau goes beyond his immediate focus on Swiss current events to gesture at a more general history of unresolved 20th-century injustices. Rau is not alone in endeavoring to re-write the foundational myths of his native country: I have written elsewhere about the work of organizations such as INES, which inscribes the experience of new Swiss citizens and second-generation immigrants into the national narrative, and places their experience in the broader context of a globalized, neo-liberal world order. There is also an important precedent for using the Tell story as an allegory for events other than the founding of Switzerland—and that precedent is to be found in Schiller’s play itself, in which the Swiss battle for independence against the Hapsburgs can also be read as a plea for a unified German resistance to Napoleon, who just two years after the first production of Wilhelm Tell in 1804 was to supplant the Holy Roman Empire with a devastating imperial project of his own.

This past Friday, February 24, 2023, was the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and Milo Rau could plausibly have made of his Tell an allegory of that conflict, with Zelensky as Tell and Putin as Gessler. Rau, of course, began planning and rehearsing his production in 2021, before the current phase of Russian aggression had commenced; and his focus in the project, as it has been in various other of his highly political productions, has been trained from the start on the very real problems arising from the specific location of each “drama”. Nevertheless, there is also a very real (and actionable) “Swiss angle” to the Ukrainian crisis. For while the official Swiss line has been solidarity with Ukraine, there are indications that Switzerland continues to serve as a major hub for Russian commodities, including coal and oil, and thus indirectly to finance Putin’s war effort. The Swiss government, meanwhile, does nothing to control or reduce this lucrative business; in fact, it positively encourages it, with various regimes of fiscal lenience. Furthermore, the vast majority of Russian assets deposited in Swiss financial institutions, or held in the form of real estate, equities, art, and fleets of motorized vehicles, has not been frozen.

Perhaps, in a future revival of his Wilhelm Tell, Milo Rau will include an indictment of those Swiss trading companies, banks, and government institutions that profit from the conflicts raging beyond the securely neutral borders of Switzerland. Perhaps he will take up that ax, which the ideal Swiss is meant to keep to hand, and use it against those abroad who are building new empires—or against those at home complicit with such builders.