by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

And You May Find Yourself Living in an Age of Mass Extinction…. So begins Timothy Morton’s latest book, All Art is Ecological.

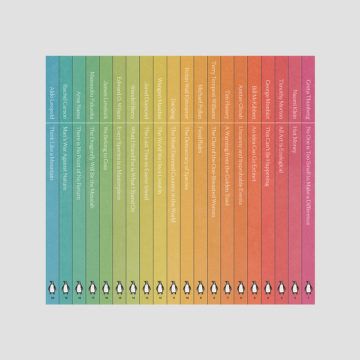

Published as part of Penguin’s new Green Ideas Series, this slim paperback sits alongside nineteen other works of environmental writing. From farmers and biologists to artists and philosophers, spanning decades, the books offer a wide range of perspectives, which Chloe Currens, the editor of the series, says serves to present an evolving ecosystem of environmental writing.

Along with classics like Masanobu Fukuoka’s The Dragonfly Will Be the Messiah and Rachel Carson’s The Silent Spring; there is the work of many contemporary thinkers, such as Greta Thunberg’s No One is Too Small to Make a Difference, Amitav Ghosh’s Uncanny and Improbable Events, and George Monbiot’s This can’t be happening.

I wanted to read them all—but I started with Timothy Morton, who has been called “the philosopher prophet of the Anthropocene.” A big fan of his writing, I think Timothy Morton is pretty much the most exciting thinker alive. I was, therefore, not surprised to find myself challenged from the very first sentence.

What does this mean exactly: You MIGHT find yourself living in an age of mass extinction?

Why the subjunctive?

And what do you think about his choice of “age of mass extinction” over climate change and global warming?

Morton says that climate change is too weak, and so he prefers global warming– since it is focused on the actual effect of climate change. But he then suggests that the ultimate result is the mass extinction event that we are, in fact, experiencing.

That a massive animal and plant extinction is now unfolding is irrefutable, but what is so crucial about this sixth such event is that the asteroid causing the die-off is us.

We could do something.

But then, why the subjunctive? Shouldn’t the opening sentence of his book be something more like, “You ARE living through an age of mass extinction?”

His argument goes something like this: By turning the issue into a definitive yes or no (verbally voting: I believe or I don’t believe), we lose the actual experience of being in the uncanny. In the middle of a catastrophe.

What happened to all the flies? Were there always this many wildfires in Southern California?

Things look the same, but something is off…

It’s not unlike the experience of a car accident or a natural disaster. Time slows down and there is an undeniable feeling unreality.

Morton is concerned with the way we are talking about the issues and how the conversation is dominated by a type of person who is endlessly “concerned” –and worse takes to telling other people what they should be doing.

He says,

“Let’s think about the delivery mode of ecological advice– drive less, shop locally, save energy, all the usual “should” that we hear again and again. Either we are being preached to as individuals, being made to feel bad and encouraged to change our habits, so that maybe we will feel better, because we think others think of us differently –or we are being lectured at, made to feel powerless, because the thought of revolution or other kinds of political change are very inspiring, but also bring up thoughts of how they might be resisted or constrained: the powers that be are too great, revolutions are always co-opted.”

In Morton’s terms that means thinking along the lines of agricultural religion—Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, and so on, thinking characterized by hierarchal views, utilizing the unambiguous language of good and bad, us and them.

But the sky is falling –and we cannot look away; not in denials, nor worse, in smug blame-gaming (just before we head out to load up at Costco or vent on carbon heavy social media). One of Morton’s interesting points is how global warming inspires in us a petrifying hypocrisy, lameness, and weakness. The topic of climate is too mind-bogglingly big and new. There are no “right” answers, and all conversations break down since any one approach will trivialize the problem and inevitably be wrong.

So what can we do?

2.

2.

All art is ecological

In Heidegger’s later work, the role of art was paramount. Heidegger was mainly interested in works considered “masterpieces.” Great art, he said, not only expresses “truth” in a culture but provides a springboard from which “that which is” can be revealed. Works of art are not merely representations of the way things are, however, but function to reveal and evolve a community’s shared understanding. Each time a new artwork is added to any culture, the meaning of what it is to exist is inherently changed.

The famous example is of a Greek Temple.

As Heidegger scholar Hubert Dreyfus explained it: “The temple draws the people who act in its light to clarify, unify, and extend the reach of its style, but being a material thing, it resists rationalization. And since no interpretation can ever completely capture what the work means, the temple sets up a struggle between earth and world. The result is fruitful in that the conflict of interpretations that ensues generates a culture’s history.”

When the ancient Greek pagans entered the colorful temples to pray, they were experiencing the space very differently from how American college students on their grand tour experience the ruins today. Meaning is not intrinsic to the building itself. How it is lit up in people’s imagination is based on the shared practices of the culture. But the works of art do not merely passively reflect those values back to people but rather assert them actively.

Art historian James Elkins wrote a wonderful book, called Pictures and Tears, about people who cry in front of art (the so-called Stendhal syndrome), Elkin notes that Rothko is the modern painter most famous for causing viewers to cry.

Coincidentally, Morton lives near the Rothko Chapel in Houston and has watched people leave unmoved while others sit for hours soaking in the paintings. And he reminds is that something peculiar can happen to people as they stand in front of great works of art.

They might find themselves gobsmacked.

Like being sucked into a portal. A kind of mind-meld that can happen.

Even if they have never broken down and cried, I think most people have felt overwhelmed by the presence of a great work of art. My friend Brooks has described it as hyperventilation.

What is essential to this experience, says Morton (brilliantly, I think), “boils down to ambiguity: how things can appear to be oscillating between familiar and strange.”

Art, then, can provide a language to understand the liminal and transcend the political. Art has the capacity to transform us and our relationship to the world. A problem of the scale of human-caused global warming defies simplistic thinking and dichotomization. But our brains on art might point toward a way forward to transcend our current mode of thinking. This current mode of thinking being what has gotten us into such trouble in the world.

3.

3.

Hyperobjects and Attunement

Several years ago in these pages, I pledged to reduce my carbon footprint by 20%. From a starting point of a fair amount of waste, it was not hard. I achieved my goal, but in the process, I saw how hard it was for me–a non-driver in Los Angeles– to reduce my reliance on Amazon.

Someone left a comment to that post, saying something like:

“Just don’t buy things. It’s not that hard.”

His words were a provocation.

It is so simple: Just don’t buy things… over the years, as I further challenge myself to reduce my impact, more and more, I realize that the problem can’t be understood simply as fixing my own rampant consumerism or bringing in green energy (two things I feel passionate about), because the underlying word-view that sees animals and plants– and the soil itself– as a resource is what needs to be addressed.

Morton is urging us to revolutionize the way we see the world; for it is in this lack of understanding of interconnectedness that is leading to our ruin.

And I do believe we are on the precipice of a new paradigm. More and more intellectuals—from Timothy Morton and Eva Meijir to Bay Area Greats: Donna Haraway, Anna Tsing, Michael Pollan and Jenny Odell, we are hearing about a new way of being in the world. Starting with the Great Donna Haraway, these thinkers are not only telling us we need to stay with the trouble, but they are heralding a new age of interspecies democracy and solidarity with non-human people.

How do we tune into this new understanding?

Morton asks: Do you have a cat? Do you pet your cat?

Well, that is ecological.

He says: Go to the garden store and smell the fragrance of the leaves.

Start there.

++

To Read:

Timothy Morton’s All Art is Ecological (Penguin Green Ideas)

Bill Benzon’s post Timothy Morton Meditates on the Millennium Falcon and Futurality

Other books that changed the way I look at the world

Further Reading on 3QD

On Ghosh and the literature of climate change: Are We Deranged?

Eyes Swimming In Tears (Stendhal Syndrome)

On the new paradigm: An Inter-Species Crowd: How To Talk To Animals And Space Aliens