by Andrea Scrima

Lydia Hamann and Kaj Osteroth have been working as a collaborative team since 2008. I got to know them in January and February of this year, when they began a year-long residency at the Villa Romana in Florence that was abruptly cut short in early March by the pandemic and the lockdown measures that followed. Hamann and Osteroth studied fine arts in Berlin; their collaborative works—conceptual, feminist, immersed in dialogue and rife with external reference, with one foot firmly planted in queer theory and the other in visual studies— have already acquired an encyclopedic character and have been shown internationally to great acclaim. Their Radical Admiration project spans an impressively prolific period of artistic cooperation that has gone beyond mere rediscovery to critically and convincingly revise historiography and correct the erasures of seminal women artists from the contemporary canon.

Photo: Timothy Speed

Andrea Scrima: Kaj, Lydia, the two of you have been working together on a long-term painting project commemorating a selection of contemporary women artists; over the course of the past thirteen years, a large body of work has evolved that’s attracted the attention of international curators. How did the idea of collaborating first come about?

Kaj Osteroth: The beauty about a long-term collaboration like ours is that the story has been re-written and adapted as we’ve gone along. And each of us recalls a slightly different version.

I like to remember the beginning as a tiny but sparkling, breathtaking first thought: ***this might work***!!! Which became a practice and an even more serious commitment towards one another. That was in 2007, when Lydia and Emma Williams were putting together a workshop for Lady-Fest and invited me to become part of the small initiating group. The idea of continuing to work together was born in never-ending summer talks between Lydia and myself, most likely involving many other people, almost all over Berlin. Today it feels as though we had been meandering and tingling all summer long, until I moved into Lydia’s shared studio space and we began to give our words visual shape. The fact is, we actually started painting much later, because in 2007 we were both still busy finishing university, writing and trying to satisfy the requirements of the academic system.

A.S.: What have been some of the difficulties you’ve encountered in collaboration?

K.O.: Oh yes, the difficulties. Thirteen years of joint forces, and in the middle of the current Corona crisis, stuck at home, making space for kids and partners, it’s hard to recall the difficulties. Or to put it differently: the luxury of focusing at all results mainly in a loving gaze at our difficulties, seen through rose-colored glasses.

As for how the idea of collaborating first came about: previously, we had each been involved in several collaborative processes, and so we were familiar with the issues and methodologies involved in working in and as a collective. We had a pretty clear idea of what we expected, and an even better idea of what we did not want to reproduce. But we both had a strong desire to work collaboratively.

At first, it was a lot about getting to know each other. This also meant understanding that two individuals bring many different ideas and perceptions, issues, desires, and oppositions to the table. And many, many differences that cannot simply be overcome or sorted out through conversation. And these differences matter! They make it possible to form ideas and thoughts in many productive ways, but they can also become a problem, they’re irritating and frustrating, force us to talk, admit things, own up to feelings. Strong feelings, ugly feelings, never-ending loops of both. Ideally, they become part of a solution that offers a new understanding and new approaches to how to work together and/or a give rise to a new artwork.

A.S.: And so radical admiration also becomes a challenge in the sense of practicing it with one another, within the collaborative relationship?

K.O.: Yes, it became a powerful force in our collaboration. Sorting out our shit. And it’s not possible to talk about radical admiration without giving our process some attention.

Lydia Hamann: We developed a pretty generous, “good enough” way with each other over the years, with the things we produce, the (different) way(s) we paint, how to deal with misunderstandings and how to react to each other. . .

A.S.: The title of the series—Radical Admiration—both sets the agenda and defines the motivating force of the work. How does the collaborative decision-making process work?

K.O.: First of all, I’d like to say that there were individual and shared reference points and observations that became absorbed into this joint adventure. Previously, I had been working with Beatrice E. Stammer and Bettina Knaup on the feminist archive project re.act.feminism, which was presented in 2013 at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin. A paradise for feminist performance art, and obviously a strong reminder of how art-historical writing has eliminated so many amazing works in the larger collective narrative.

L.H.: In the paintings of our series Radical Admiration, we want to represent feminist artists, celebrate them, show their achievements, but also formulate a very subtle rebuke, because in the bigger picture, we’re talking about a big-time gender gap and p.o.c. gap and subjugation. And in the meantime, they’re all out there doing fantastic stuff that not enough people ever hear about. . .

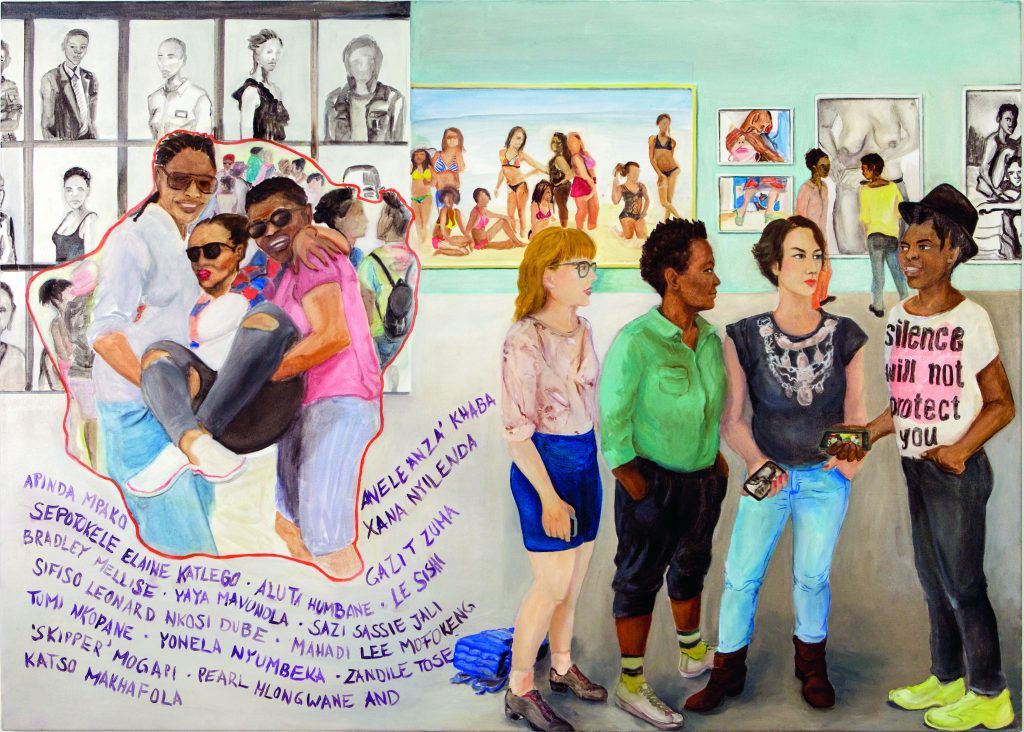

Oil on canvas, 115 x 160 cm. Photo: Smina Bluth

K.O.: For us, it was wonderful to see all these amazing strategies that had already existed in the 1960s and 1970s. We didn’t have to invent a thing, but we had to name our references. To us, this was completely natural and self-evident, but apparently others didn’t find it necessary or had decided against it. . . So this is where we found a starting point for our work.

L.H.: To admire feminist artists is a wake-up call to become more adventurous, to do your own thing and allow for more fantasy. It reaffirms themes and issues that Kaj and I always talk about and struggle with, issues that inspire us to move on and create, like overcoming envy and deconstructing power dynamics.

We were completely mesmerized by all these biographies and aspects that came to light during the last several decades as visual and cultural studies scholars and feminist scholars shifted the focus of the art spotlight. . .

We became aware that BIPoC and feminist artists were being written out of history, but we didn’t want to make it into a negative trope, even though the outrage we felt was real and sky-high. We wanted to admire, because we didn’t want any of that criticism, insurrection, or protest, any of that—let’s call it the white male artist narrative of being in power and in possession of the right perspective on all things—we didn’t want to take on that voice or tone and start criticizing and performing the same old same old with it all over again. . . and so for us, admiration is more like a gesture of refusal, a way not to say yes, we know better. Seriously, though, any other approach would have led us into an anthologizing type of work that would span decades, and that is not what we were after. [laughs]

K.O.: Yes, I guess we really have achieved this together. But it developed slowly. We didn’t start with the idea of admiration, we started, as Lydia puts it, with an affirmative take. It was about allowing ourselves a subjective, loving, enthusiastic look, and it was a lot about whom we would like to introduce to a younger audience. Whom we would have loved, as teenagers, to have been introduced to: in school, at home, and later, at the university. The notion of admiration came while we were working our way through the amazing works and positions and activities of each of the artists. And at some point, the notion radical was added. . . it already existed when we were in Johannesburg, and so it came to us quite early.

A.S.: I imagine the radicality of the work became clearer when you understood the political implications of what you were doing.

L.H.: We were also, it should be said, aiming at a young female audience.

Radical admiration works as a self-identifying, self-professing strategy, and not as a tool of critique. For us, it forms a basis for feeling, for being with feminist colleagues and forerunners, for having a feminist home—and not being doomed to go CRAZY.

K.O.: Exactly, Lydia, the feminist home. When Andrea and I spent time together in Florence (on the couch in the studio), I was somehow not so sure anymore how feminist my standing in the world currently is. Being basically in an intense mother-child situation, trying to make the little one feel comfortable in a new environment and daycare center, while looking at a world of racism, misogyny, and madness everywhere. No energy and no big thoughts left. So yes: feeling connected and also personally connecting with other feminists is the thing! Thank you for reminding me!

A.S.: I remember how existential those first years of motherhood can be, what those few hours each day become when you can finally bring your child to daycare. And it’s incredible how, in professional situations, women are still required to keep their motherhood to themselves. But child or no child, in an art world in which women artists are for the most part stuck with the short end of the stick, you could almost say there’s a radical degree of modesty involved in turning admiration into an artistic position.

K.O.: I like the way that sounds, but could you elaborate a bit?

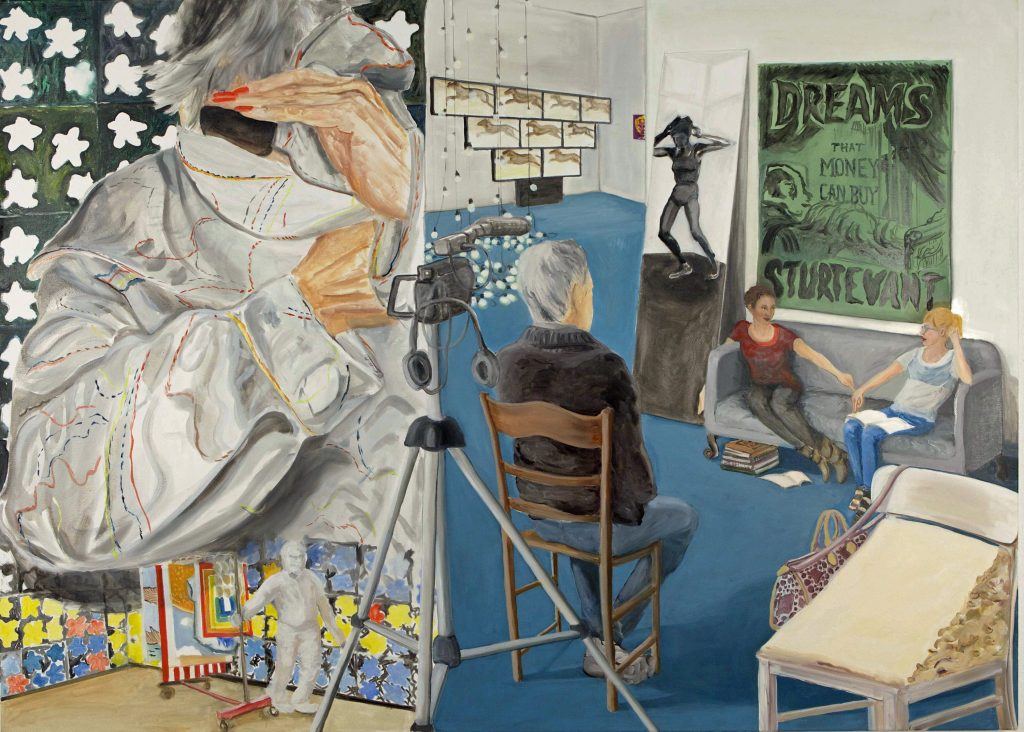

Oil on canvas, 115 x 160 cm, photo: Smina Bluth

A.S.: So much of what passes for artistic success is about defining a style and sticking to it. The art world is a highly competitive field, and it’s unusual for an ambitious artist to dedicate their work to artists they admire. For a woman artist, you could argue that it’s a form of suicide—Elaine Sturtevant didn’t need to be written out of art history, she was simply ignored. And so you’ve turned the subordinate position implied by admiration upside-down and made it into a superpower. And, it has to be said, you succeeded.

K.O.: Well, modesty = the moment we refuse to reproduce what we already know, that is: research, facts, big and bigger thoughts, individual geniuses, male and female alike, and, as Lydia says, anticipate a “with and amongst” feminist colleagues and forerunners.

L.H.: Yes, you’ve named it, but the humble position is not all that uncommon: there are many forms of empathetic artistic production, some of them feminist, that consist of bonds to other artists and, as in Elaine Sturtevant’s case, involve a lot of funky twists and jokes, as well. In the performative arts, it’s become common to reference one another, to copy one another, and Elaine discovered that painting is also a highly performative action. (At the same time, we always asked ourselves who are we to admire so shamelessly. . . ) But yes, when we proceeded with the admirations, we found that it’s a sort of bracket that works and that has its playful and liberating turns for us.

K.O.: But you asked how the collaborative decision-making process works. Lydia. Kaj. Couch. Coffee. Issues. . .

L.H.: Exactly. Food and issues are brought to the couch and chewed over thoroughly. . . We often give each other an audience with things we’re struggling to give a form to, as they also don’t seem to appear in the world of art production. That’s why we also love these feminist artists, because they addressed and criticized the narrowness of patriarchy and subjugated representation before us and so we can relate. . . Another thing that I find extremely beneficial is that when we sit together like this, it’s much easier to reflect ideas that are connected to our purpose. I think that bouncing ideas back and forth makes it easier to then throw out the ideas that are too normative, or ideas that are based on too much “hard work,” or on getting lost in ideas that don’t go anywhere. I remember tons of situations where Kaj was like, “. . . come on Lydia, don’t get lost researching this or that, come on, let’s just finish this painting here!” Marvelous!

A.S.: The couch becomes a third author/protagonist in the works—it’s the stage where the drama unfolds, where hours and hours of conversation and debate have taken place.

K.O.: Hmmm. Why not a protagonist. . . I guess we have not given it (her) an active part yet, it was a threesome, the couch more or less a space for the two of us and guests to come together. But when I think about it, especially due to the current Corona time-out, it feels like the couch is indeed a protagonist, that is, this joint adventure is missing, it no longer has its former drive. I feel a strong longing to return to the couch, allow her to do her magic, find comfort and feel cared for. Without the couch, we all fall back into our own individual spheres. Recently, the couch has become a rather rare mutual space. Family has become stronger. Survival is more demanding. Staying sane with all these cuts and restrictions in times of Corona is a real challenge. . . But if she was a protagonist, we could address her. . .

L.H.: I love this idea that our couch has a hidden agenda, and that she performs magic on us when we sit on her. It’s like a cinematic narrative of the lifelong spell inanimate objects can cast on their subjects (maybe she even gave us clues on our first take on feminist artists. . . ).

A.S.: Who were the first artists you created work about? Could you tell us some of the stories about the individual paintings?

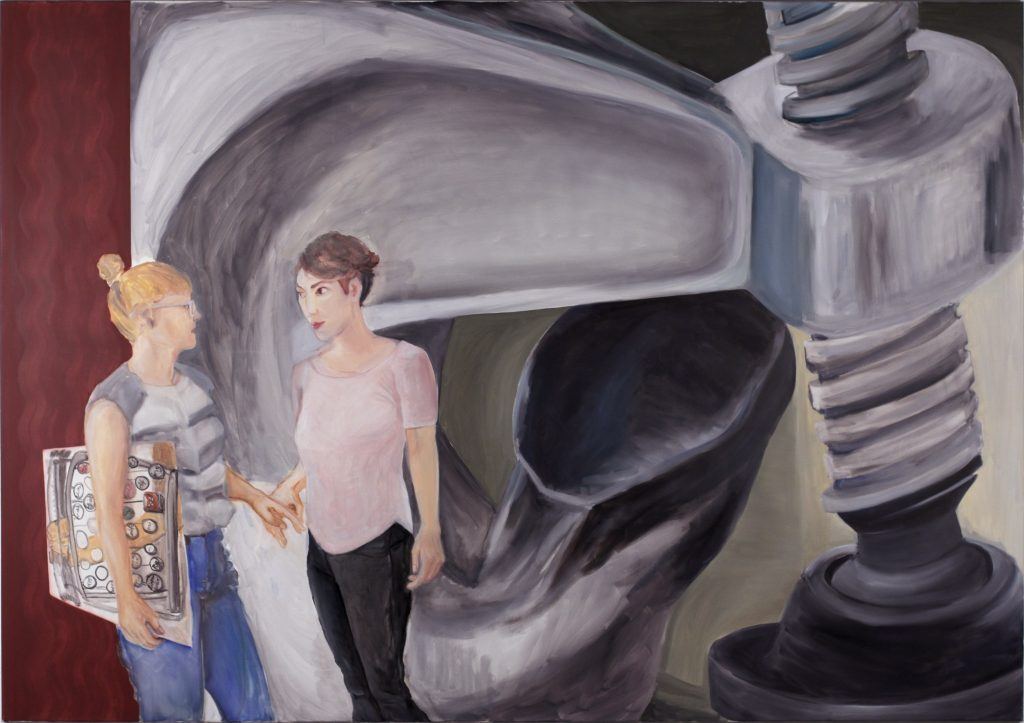

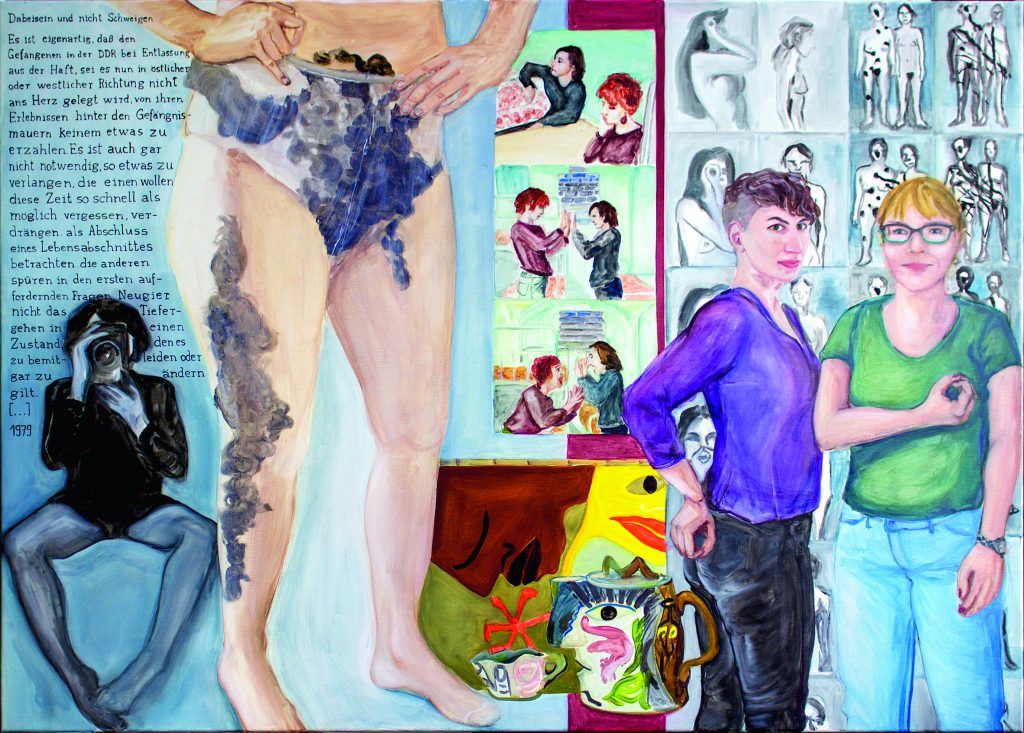

Oil on canvas, 230 x 160 cm, photo: Smina Bluth

K.O.: Not sure if we mentioned our LIST. The list of artists we would love to work with, get to know better, admire together. Obviously, the list was long, way too long, and we had to start somewhere. Elaine Sturtevant was indeed the first artist we chose. She’d just recently passed away, and not knowing how much this first approach would shape the following images and admirations, starting with one who’d re-done other artists as she had was a brilliant decision and taught us so much.

So once we decided to dive into Lee Lozano’s work, it was a beautiful awareness that we would—very Sturtevant-like—not only study Lozano’s artworks, but also her intense writings and manuals. As she often instructed herself very clearly on how and when to work/paint/perform. This was the greatest pleasure. Painting a painter’s paintings. Our image of Lozano was also huge, twice the size of the previously painted one. Regarding the canvas format, we always had the book in mind, but we also were taking some artists friends’ suggestions seriously to keep their presentation in mind, and how it would be more interesting to vary the sizes. . . anyhow. This one was large, and it was so perfect for messing around with Lee Lozano and her way of painting and thinking.

But somehow—and this is maybe the interesting part—we were also disappointed, as she refused to talk to women. So we refused to put her image into the picture.

A.S.: This is another interesting question your work raises: how much meaning you decide to attribute to this communication or lack of communication with the admired artist.

K.O.: We refused, and still do, to deliver an objective, academic, best practices, clever, smart take on the artists. We prefer—and I guess I am mentioning this here as it becomes part of my/our writing again—to make it a lived, shared moment. I guess the couch that we stress so much in Radical Admiration—A Feminist Picture Book becomes more and more the vehicle for what this is all about. Even now, with the project taking on new forms and entanglements. I’m just realizing how difficult it is to maintain the openness and the ease that we allow ourselves in order to enter our shared realm and complex real-time data exchange. . . sitting at the other end of a written document. How does this feel for you, Lydia? We talk a lot on the phone, discussing and offering one another access to this text. . . and once we open the laptop, it’s you there and me here.

L.H.: Yes, with you there, and me here . . . I feel like many do nowadays, cut off and on the computer too much and stuck in a multitasking of childcare and job maintenance. Like you, I yearn for our collective space, our couch, for our plans. . . this whole distancing is nothing like the way we work. . .

I recall that we talked about displaying the many layers in the collaborative, academic, painterly, cinematic, musical, and discursive nature of Vaginal Davis’s work, which is just stunning. We arranged it in this multilayered way because this is how she works, she chooses to go through genre walls like they’re liquid, she references wildly, her works and pieces are entanglements of knowledge, gossip, and other artistic achievements, or sometimes she chooses to copy, steal, or repeat other people’s artwork (sometimes Vanessa Beecroft, for example, but not exclusively) to change their narrative in a way that addresses their sexist and/or supremacist content or white ignorance, to make it more inclusive, more real. But her painterly approach is pretty kick-ass, too. She works with material and pencils from a makeup palette and uses female cosmetics such as creams and perfume, and she also has tons of references and heroines to play with, which is a very inspiring way to make a painting.

Kaj, how and why did we do the Polonaise in the upper right corner?

K.O.: So in this image, we have three distinct layers that each stand for a certain aspect we were able to identify for ourselves as crucial. The small group of people in the foreground represents the group Cheap. We saw some of their plays and stalked others online and through their own media output.

There are also Lydia and Kaj performing Vaginal Davis performing Vanessa Beecroft.

In the middle ground, you see Dr. Vaginal Davis and Esteban Muñoz in conversation. . . I just quickly Googled and found it and suddenly, I magically find myself in the middle of all the original excitement over this mutual work again. Of all the treasures we looked at together, thinking, talking, struggling, becoming mesmerized over it! Actually, I don’t know if we stressed that enough in our publication. If our audience would do exactly this: look at the image, stalk the artist online, and find and follow our threads and tiny narratives. . . so much fun. So much admiration. So much entanglement.

A.S.: What’s happening in the background?

K.O.: Well, the Polonaise Lydia mentioned is our summary of a beautiful piece of writing by Marc Siegel on gossip in Vaginal Davis’s work. We had a list of figures Marc recalls from Davis’s performances. This list of figures builds up to a strong take on who meets whom, who is representing whom, and who believes to know who one might be and so on and so forth. . . Gossip at its best. So we used this group up there in the upper right corner, in order of appearance, as a Polonaise, a quick draft, and it turned out to be hilarious. We loved the Warhol so much, we didn’t dare add another layer.

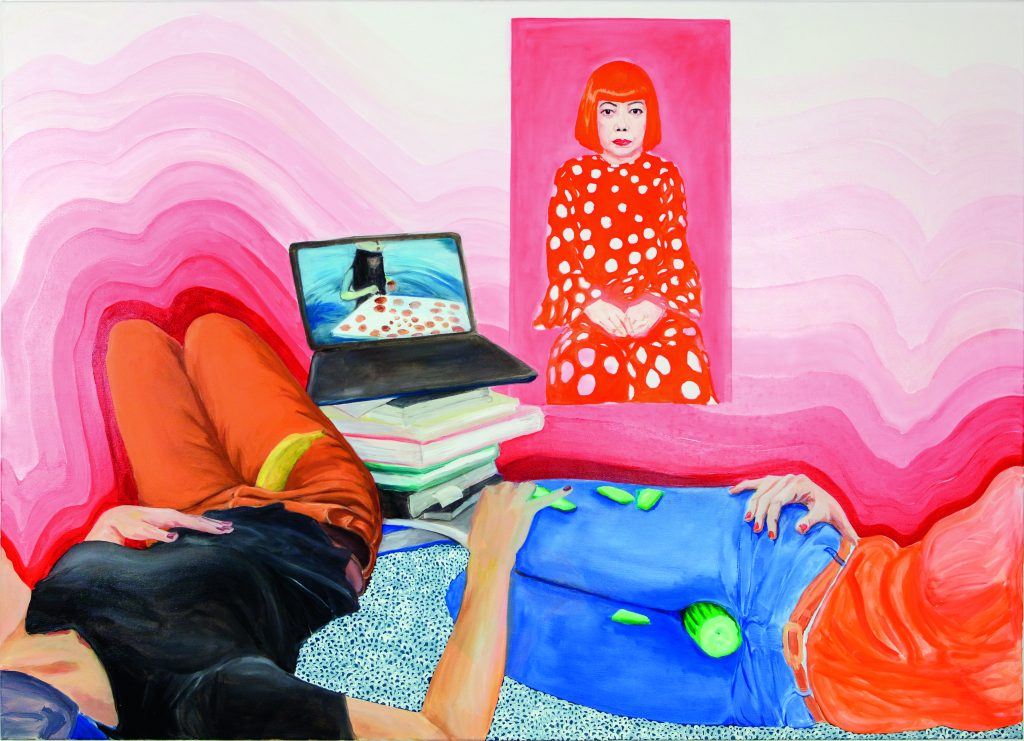

Oil on canvas, 115 x 160 cm, photo: Smina Bluth

L.H.: I remember our day in the studio admiring (researching) Yayoi Kusama. We met in the morning, and it was our habit that each of us bring something to eat, as we always devour heaps when we work together. . . we had this funny collection of food, like bananas, cucumbers, and chocolate. . . across from our couch, we had this pile of books about Yayoi, as our public library is very well stacked on Kusama. We placed a laptop on the pile to watch her painting dots in one of her films from the seventies, where she is so young and enters the scene on a horse, equipped with brushes to paint dots on the landscape around her. At some point, we were pretty filled up with her work, all the big catalogues and her own autobiography and we were discussing whether it was already time to go out again for lunch or coffee—another of our habits, that we leave the studio to eat or have a coffee and get some distance. . .

We were not really coming up with any mutual ideas about admiring her, and so while we were wandering outside along the canal, we sat down on a bench and discussed our goal again, and . . . we came to the core of our project, which was that we also wanted to make visible how we admire, like really, physically, how we work and what we do and who we are and how you can relate, so we drew a quick sketch and we were just sure that we were going to paint our breakfast scene. . . so it’s pretty much like an impressionist scene, a snapshot, or a cut-out of two young women in a leisurely setting and an atmospheric wave of being overwhelmed by this artist. . . I think we wanted the pink waves to symbolize her being the inventor of environments as an art practice, something Andy Warhol gets credit for, but actually he copied her practice in the early ’60s. . .

But then Kaj also wanted to pay respect to her phallic works, and immediately we saw our breakfast in light of another purpose, and then we both had to laugh so hard, because we’d subconsciously brought these phallic foods with us! [laughs]

A.S.: Have you noticed any gender-based difference in the reception of your work, i.e. how do men react to it, how do women react to it, and have there been surprises?

K.O.: The reception of our work does not necessary run along gender lines, but along the Eurocentric, mainly white, patriarchal, heteronormative academic model of worthy painting results and practices.

We somehow noticed that our work is perceived in a much friendlier way in São Paulo or Johannesburg, for instance. And to receive a broader recognition in Berlin, it took curator Gabi Ngcobo and her team: Nomaduma Rosa Masilela, Yvette Mutumba, Thiago de Paula Souza, and Serubiri Moses. Even though the paintings for the book had long been dry and the crowd funding campaign to raise the money long set up. . . it took another year and this amazing invitation to finally make it happen.

L.H.: I didn’t really notice how men reacted to it; womxn, however, reacted very strongly, for example at the 2018 berlin biennale “We Don’t Need Another Hero,” there was a strong backflow from the people working in the show to mediate the artworks; they were very happy about our work, because for them it addressed a topic in an easy way that is not often approached on this meta-level, and that, for them, explained itself very beautifully to the audience and to the many schoolchildren there, who also got a glimpse at feminism. In São Paulo, our wonderful curator Isabella Rjeille and director of the MASP Adriano Pedrosa were big fans of the work, and we were also very happy to show our paintings there as they have also given big shows to topics related to feminist as well as decolonializing and deconstructing histories.

Oil on canvas, 115 x 160 cm, photo: Smina Bluth

A.S.: The painting Admiring Jutta Koether: Overlapping and Other Activities from 2015 is one of my favorites—can you talk a bit about the individual parts? I see the two of you—you paint yourselves into every painting as observers, thinkers, debaters—but is that Koether on the left?

K.O.: Yes. The artist portraying herself as Poussin, reflecting a self-portrait of Poussin, which hangs today in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. It is a painting from the series Berliner Schlüssel (Berlin Keys), exhibited at Buchholz in Berlin in 2011. This series provided the color range and style for our image. It was one of the first admirations we did, so we definitely had a strong desire to dive into the Koether universe.

I love looking at our Koether admiration, especially when I’m leafing through the book. You have to admit, it works exceptionally well in the book format. In our portrait of her as Poussin, she looks completely annoyed or even mad, with her eyes crossed, almost as if she was possessed. This is, if you will, a productive accident. Somehow, the Koether Poussin got hold of us, grabbed us.

L.H.: Yes Kaj, it’s true that she really grabbed us, I think the mood we were in when we painted her admiration was that we felt possessed by her, and by her as Poussin, somehow it’s a ghost story. Because for us, when she performs Poussin, she already peels away so many layers of the old masters story, and we wanted to fall into it, to be taken up and swept away by this unsettling swirl of history. In a way, she produces a kind of fake that we would like to believe in; she also poses an important retrospective question: what about all the other artists of the last centuries that we don’t know of, don’t see, never hear about?

K.O.: The admiration for Jutta Koether seems to evolve, or rather it’s being reinvented over time. We really like what she represents, the wide range from painting to collaborative music projects, performances and writings and all the overlapping aspects of such a broad practice. This admiration goes back to the time when we were still at university. We were interested in the fact that she did not seem to perform the artist role in the way we’d been taught.

My first encounter with her work was an installation featured in texte zur kunst that she did in an apartment in New York (The Inside Job, 1992). The visitors were forced to walk across a floor painting titled The One one, and inevitably left tracks. The space in the center of our painting pretty much recalls Koether’s studio-apartment. But Lydia and I don’t walk across her floor painting; instead, we remain in front of the empty canvas, equipped with brushes, ready to become part of Koether’s arrangement.

We added a portrait she did of Peaches, as we liked the idea of us admiring her, admiring an artist we also can relate to. Many of the other elements, the lightning, the pot, and the branch are fragments from her Berliner Schlüssel series.

Oil on canvas, 115 x 160 cm, photo: Smina Bluth

A.S.: I’m also in love with Admiring Gabriele Stötzer, es wird sich das nicht ändern (Admiring Gabriele Stötzer, it won’t change that). Stötzer’s work encompasses performance, film, photography, artist’s books, prose, poems, and texts; it’s not only directed against traditional role models, but the elimination of individual personality as practiced in the former East German political system. Stötzer sat out a prison sentence for “defamation of state” after signing a petition against Wolf Biermann’s expatriation. Almost everything she did was an act of defiance.

K.O.: Talking about Gabriele Stötzer and her work feels a bit like gossiping. I guess it’s due to the fact that we’ve had some beautiful encounters with her over the years, and that her writings are very intense and we somehow feel like we know her pretty well.

Importantly, she engaged in political actions, in activism; she was a driving force of an art scene not welcomed by the state. On the one hand, it was inevitable that we were impressed and in awe, and on the other hand it’s unbelievable that until recently, she hasn’t been recognized or made the subject of (art-) historical writing. She is such an amazing role model.

As you’ve said, she was jailed as a political prisoner with criminals and murderers in the women’s penitentiary at Hoheneck/Stollberg. Besides experiencing pain and dark despair, she learned solidarity, female power, and how to survive, and she decided to become a writer.

The main figure in our admiration of Gabriele Stötzer is this pair of huge, hairy panties, a still from her super-8 film Trisal from 1986, a work she did with other women, experimenting with the body and bodily applications, exchanging the actresses’ labor with an experimental form of self-awareness.

The coffee pot and tapestry represent the crafts she created in order to survive as an artist in the GDR.

We quote two photo series from her photo book und, frauen miteinander (and, women together), 1982/83. One is Das Loch (The Hole), a naked figure pointing out all the holes and places of the human body one had to present when entering prison. In our portrait of ourselves, each of us is performing one of these gestures.

And on the very left side we quite prominently feature an abstract from Dabei sein und nicht Schweigen (To Bear Witness While Not Remaining Silent), a text written by Stötzer in 1979 in which she articulates the thought that one does not need to be forced to keep silent about one’s personal experiences in prison, as the drive to forget and move on is as strong as the lack of interest from one’s personal environment.

A.S.: The paintings contain an abundance of visual quotes—sometimes they read like encyclopedia entries, or even hieroglyphs. In formal terms, you could say that you’re creating a visual vocabulary consisting of highly compressed references to external information, and while you envisage the ideal viewer as someone who begins research on the spot, I’m wondering about this on another level. Because it lends a highly textual aspect to the work, which I find very interesting.

L.H.: In the admirations we work as composers, we make compositions. Artist X has to be admired, in the form of an act or a painting; we find an image for our admiration of a certain cultural practice. In our work in São Paulo, we talked about the fact that we weren’t so much composing as composting (Staying with the Trouble, by Donna J. Haraway, who also has a great, very feminist practice of referencing and quoting). We keep the artistic work fluid, but not like memes—it’s more like situationist mind maps. We build a net of references, we search out every last bit and feel it all the way through, we find a relatedness, a picture or just a quote—a method that lies in the work of the admirer, the copyist. We work with knowledge production and experience creative moments together, so these textual elements might be traces of our conversations in which we remember certain aspect or feelings.

At this point, we feel that it’s not a work in circulation, like a meme, where we would approach the original as a mere vessel of effects, even though it’s drained of effect. We don’t want to compose content that departs from the original individual capabilities, but to reinforce them, get sucked into them.

Diving in, seeing more and more the more you see. It’s like that with knowledge and its effects, it opens things up. . .

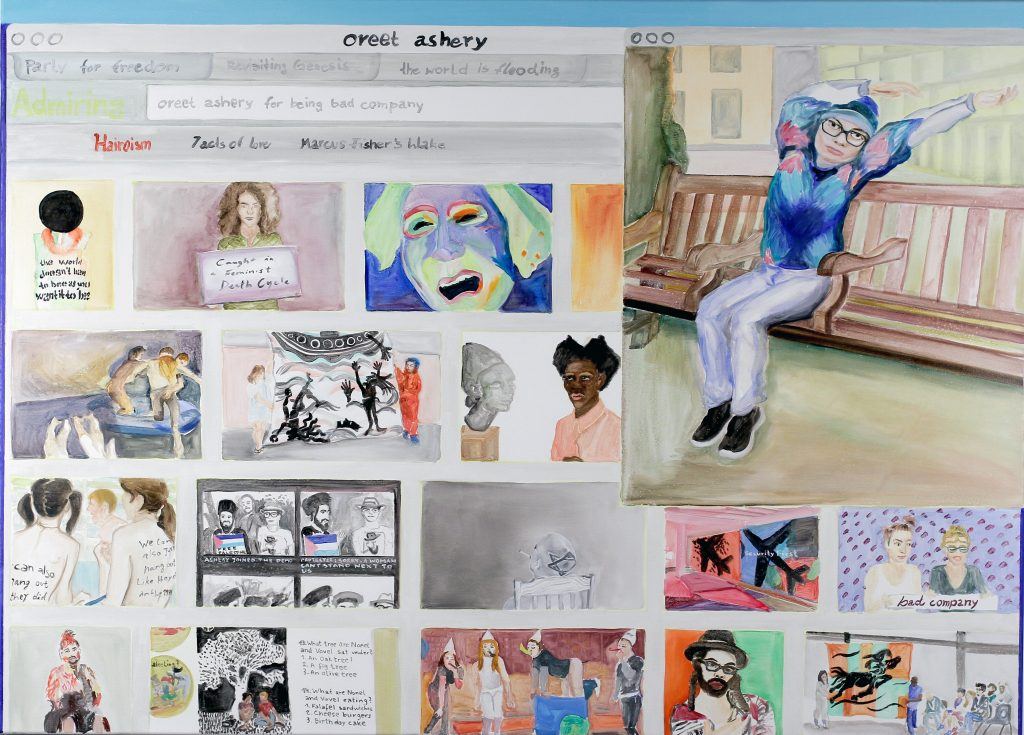

Oil on canvas, 115 x 160 cm, photo: Smina Bluth

A.S.: Can we decode at least one of these pieces? The painting Admiring Oreet Ashery, for Being Bad Company, reads almost like a comic strip; when you look more closely, the browser tabs at the top suggest a kind of simulated Google image search. We see an image of the Israeli artist disguised as a Hasidic Jew; we see references to other installations and performances.

L.H.: Oreet Ashery’s work became so multifaceted and versatile over the past few decades, even though she is a rather young artist compared to others in our admiration list. We were so impressed by her works and her extremely different approaches and methods, which build upon each other and range from performance (Marcus Fisher series), collective work (e.g. Falafel Road with Larissa Sansour), participatory performance (The World is Flooding), to installation (Animal with a Language), video (web series Revisiting Genesis), and teaching and mentoring. We tried once or twice to work with another medium but failed, so it’s full of a certain desire and envy that we admire Oreet Ashery. In our view, it’s maybe already a full web of works, a polytropic array, that’s why we touch down with the browser window. She was always on our list, as she was often a reference artist in our queer and art-activist study groups. Then she offered this workshop accompanying a show at the NGbK in Berlin with the title bad company, where we both took part and were finally set ablaze.

K.O.: Hmmm, did we fail? I just realized how much we love Oreet for both her collaborations and for the works she produces under her own name. And it seems so rich and belongs together, without a doubt. Regarding our collaboration and how we have been regarded, especially ever since we started getting some recognition, it seems like we are cautiously asked to stay away from individual approaches and projects. Being recognized within the art world as a collective seems to make all other efforts look like a failure. I don’t know, but perhaps the envy and admiration for Oreet’s work also has its origin in this aspect. And even if the collective aspect seems safe for us, and obviously also for the world out there, our individual projects do not lack any of the mindfulness, desire, or care that we bring to the couch in order to create together.

But back to your question. Decoding Oreet Ashery. Lydia already mentioned the wide range of her productivity that we somehow tried to represent. Maybe I’d just like to add that the choice of a “simulated Google search” also reflects our sources and tools. Even though in the case of Ashery we had several face-to-face encounters as well as physical sources and real-time exhibitions, we do rely on the information and limitations found in the world wide web.

A.S.: Kaj, Lydia, the two of you have spoken often about the feminist agenda that inhabits the act of radical admiration—not a shoring up of research and information with the intention of cementing an art historical canon, but a radical celebration of work previously marginalized or ignored. How do you see your collaborative work continuing? Can you imagine leaving the painting context and intervening in other forms?

K.O.: Actually, painting is such a small aspect of our collaboration. The current discourse and its underlying fashions allow us to think of the couch and the cloud we produce together, consisting of knowledge, thought, issue, effect, gossip (this one is new), ugly feelings, and love as a form of its own. But: you cannot and don’t want to exhibit it. Perhaps the painting as a momentary vehicle will not work for the rest of our collaborative life. It seems rather limiting, especially due to the current lack of time and shared space. So yes. Perhaps we will embrace other forms. What we would love to fabulate about is painting as labor, perhaps engaging in a much broader line of production, including more brains and hands and her-stories.

L.H.: Making art is difficult—you have to be audacious, and things only change when you work together. Some things become lighter, and some more obtrusive. Sometimes, when we thought our collaboration had come to an end, it was sparked anew by chance or luck. The place in which we meet is a shared desire for an aesthetics of refusal: we want to work together, but also not be so one-dimensional or linear. Each of us has her own projects and problems. Collectively, we want to continue our painting practice and continue to research feminist histories, radical histories, collective histories.

For me, the admiring project opened up a whole world around teaching, because it had opened up a whole new world of learning. Which is in part due to our subject, but in the bigger picture, it’s our joint efforts to approach each other, to reject and reembrace parts of ourselves in the mirroring of our collaboration. Finding a frame for our dialogic form, I often think of Autocoscienza, a collective exercise in feminist consciousness-raising as profoundly made accessible via the Italian feminist groups around Carla Lonzi et al. “The self-consciousness of one woman is incomplete and stuck if it is not reflected in the self-consciousness of another woman” (Carla Lonzi, Taci, anzi parla. Diario di una femminista, or: Shut up. Or rather, speak: Diary of a feminist, Milan, Scritti di Rivolta Femminile, 1978). Which is a field to get in touch with during our residency in Florence. . .

A.S.: Lydia, Kaj, thanks for this conversation—I can’t wait to see where this all leads the two of you in the future.