by Brooks Riley

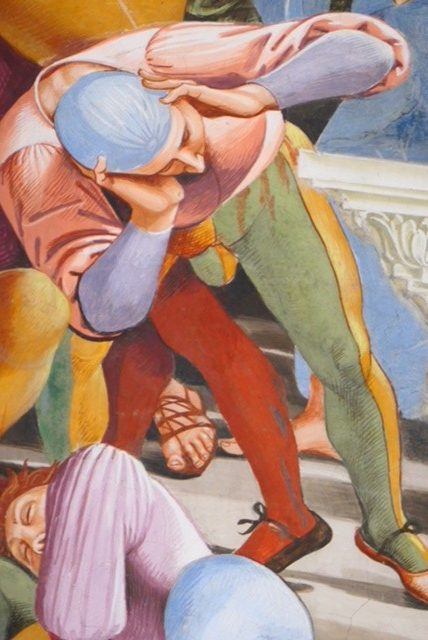

It’s not every day that a small, unexpected masterpiece shows up in your mailbox, arriving with the same modest ‘ping’ that announces the other electronic missives. This was no ordinary masterpiece. It was the photograph of a detail from Luca Signorelli’s fresco La Fine del Mondo on the entrance wall of La Cappella di San Brizio in Orvieto, the work itself a masterpiece of painterly skill and imagination, dating from ca.1500. It was taken by a good friend who spent several days with the monumental Signorelli frescoes on the interior walls of the cathedral of Orvieto.

The masterpiece I received, one small element of the arched fresco, achieved its rarified aesthetic status from having been isolated by the photographer for the frame, an act of proto-cropping used by anyone who’s ever put his eye to a viewfinder—or for that matter, anyone who’s ever opened his eyes.

We are all born with a cropping tool: It’s called focus. When we wake up in the morning, the eyes flutter open, we leave our cerebral home with its latent, chimerical images and are confronted by a giant canvas with millions of details, fuzzy around the outer edges, stretching out a full 180 degrees. Without a thought, we begin to cut away the dull bits, homing in on the alarm clock, the window, our phones, a doorknob, maybe even our fingernails. This is how we maneuver our way through the day and through life, cropping the big picture to highlight the parts we actually need to see at any given moment. Most of our time and attention are devoted to the details we’ve cropped from our greater field of vision, whether it’s the utensils we use, or the paths we take, or the signs we read.

In photography, cropping occurs before the picture is taken.

The act of photographing begins with the act of selecting a part of the whole view. Unlike eyesight, where the periphery of an examined object is subconsciously suppressed, the photographer’s selected image will emerge in quadrate form, a man-made format which not only provides a finite shape to define the subject, but contains a clear context determined by the photographer when he framed the image.

The great difference between the eye’s focus and the camera’s is that our eyes tune out the periphery of our focus, while the camera defines it. Look at a coffee cup: Your focus is centered on the cup, but you can still see the cup’s environment—the table it’s placed on, the back of a chair behind it. The whole picture never goes away, but the mind chooses not to notice it, intent on limiting the sideline noise around the object of focus, the coffee cup. An odd still life by painter Giorgio Morandi seems to ask us to realize this effect, by placing the objects at the back of a table, forcing us to take notice of the table top itself.

Sometimes the eyes want to see the whole picture. If the view’s good enough, an establishing shot may be called for, one that takes in the giant canvas of our vision—or great swathes of it—and ignores the details. This is eye-candy, what landscape photographers are going for. We can do that too, not only for pleasure but also to get our bearings in a greater circumference.

Our visual apparatus is constantly cropping in different scales, as directed by our will to see something specific or a determined area that is greater than a single object of attention.

Cropping has been around a long time. In the old days, not that long ago, if you didn’t have a darkroom, you simply picked up the scissors. Think of a wedding photo: Don’t like your new mother-in-law? Snip, snip, she’s gone, for now. Want to concentrate on the newlyweds? Snip, snip, the wedding guests are gone. Selfie-oriented? Snip, snip, the bridegroom’s gone too and it’s just you. The problem with this crude cropping technique, aside from a desire to keep the original photo, is that you’d end up with tiny snip-snippets, cut-outs with an odd fit into the wedding album. In the end, you’d have to take the negative to someone with an enlarger to make a standard-sized blow-up of the different variations you’ve made with a pair of scissors.

Long before digital there was a lot of cropping going on at the professional level: Newspapers, magazines, brochures, posters, all were engaged in reframing the visual to fit the allotted space on the page.

With the ascension of digital photography, the cropping tool has been made available to everyone, becoming so ubiquitous that it’s taken for granted. There’s no picture that can’t be made better or turned into something completely different through cropping, a tool that anyone with a processor, be it a phone or a laptop, can readily and easily utilize. Even algorithms have learned how to crop. When I open my laptop I’m often confronted by the eyes and forehead of an old selfie in the dynamic Windows tile for pictures. The 16×9 aspect ratio of that tile challenges the algorithm to crop the original photo. But why the eyes, when it could have selected the mouth and chin? Or the whole face (rendered more diminutive by that aspect ratio)? The algorithm seems to know that eyes are more engaging than chins, but there’s also the nagging suspicion that the algorithm also knows I cropped another selfie down to the eyes for an article on Leonardo da Vinci. Whatever, one is compelled to look at this tile precisely because it’s hiding something, which makes it more mysterious.

But back to that little masterpiece. With pixel density ever increasing, the benefits of the cropping tool have become essential for art historians, allowing them to study details of paintings without having to endure the scrutiny of museum guards. As the German art blog Stendhal Syndrome points out, you would set off the alarms long before you ever got close enough to see the windowpanes reflected in Dürer’s eye in his self-portrait from 1500. Thanks to a high-resolution version of the whole painting, provided by Wikipedia, I was able to zero in on those panes in an instant.

Beyond their usefulness for research, details may have aesthetic value that is independent of, if not unrelated to, the whole work, as is the case of the little masterpiece. Much of the fresco feast that took Signorelli three years to complete is devoted to the apocalypse, concurring with the long-term breaking news of our own newish millennium. Viewed as a whole, the violence of Signorelli’s imagery of catastrophe is overwhelming, with a cast of hundreds in various states of agony and bodily contortion (he was a master of anatomical diversity). In all apocalyptic visions, however, including our own, it is the individual who moves us, the everyman suffering a collective horror in his own way. The fool in this detail (is it us?) is about to fall down dead, his ribald, polychromatic fashion no longer relevant against the destiny he is about to meet. He covers his ears because he doesn’t want to know what lies ahead (do we?). He is captured in precarious mid-fall, a slow-mo nod to our own slow, agonizing downward trajectory. This tiny detail, isolated from a dense, riotous work resonates as much as the entire glorious context from which it was culled. It can stand alone, freed at last from the confines of a grand vision, free to make its own statement.

I’m not even sure that Signorelli would mind this extraction from his work, which also goes by the name of Extermination. After all, he spent a great deal of time on this small area too, mulling over the tights and their mismatched colors, finding just the right moment in the body’s gravitational journey to the ground, just the right reaction to the sounds of doom (or is this the automatic gestural reaction to horror, as it is in Edvard Munch’s The Scream?).

We are accustomed to contemplating works of art in their totality. What we haven’t fully explored or exploited are the works inside those works. We can learn to disregard the painter’s intentions for a moment and allow ourselves to bathe in another kind of aesthetic that culls from the original to create a whole new image, in some cases an abstraction of stunning beauty. A crop job on Jacopo de Pontormo’s Visitation of Mary yields several abstract images whose power emerges from the collision of unlikely colors. As separate paintings, the viewer might remark on how these amorphous, billowy shapes resemble garments. That they are in fact garments, removed from the bodies that wear them, only increases the dynamic power of shape and color in abstract form.

We are constantly wanting to know what the future holds. But few of us ask where our eyes will go to find its treasures in a world dominated by Instagram. How many dinner entrees can we bear to see twenty years from now, how many selfies, how many flowers, how many landscapes? It may be that we will find our way to a new, pattern-oriented, abstract form of aesthetics, the treasures to be found deep within the explosion of pixels that allow us to move ever closer to limits of visibility. Will the cropped drop of water on that lettuce leaf take pride of place over the whole salad in our laptop museum? This is not to say that we will abandon our snapshot mentality with its captured moments of events and people and even meals—the ongoing documentation of our lives to be re-lived by us and shared with others. But our definitions of beauty and awe may change as we explore what’s yet to be seen.

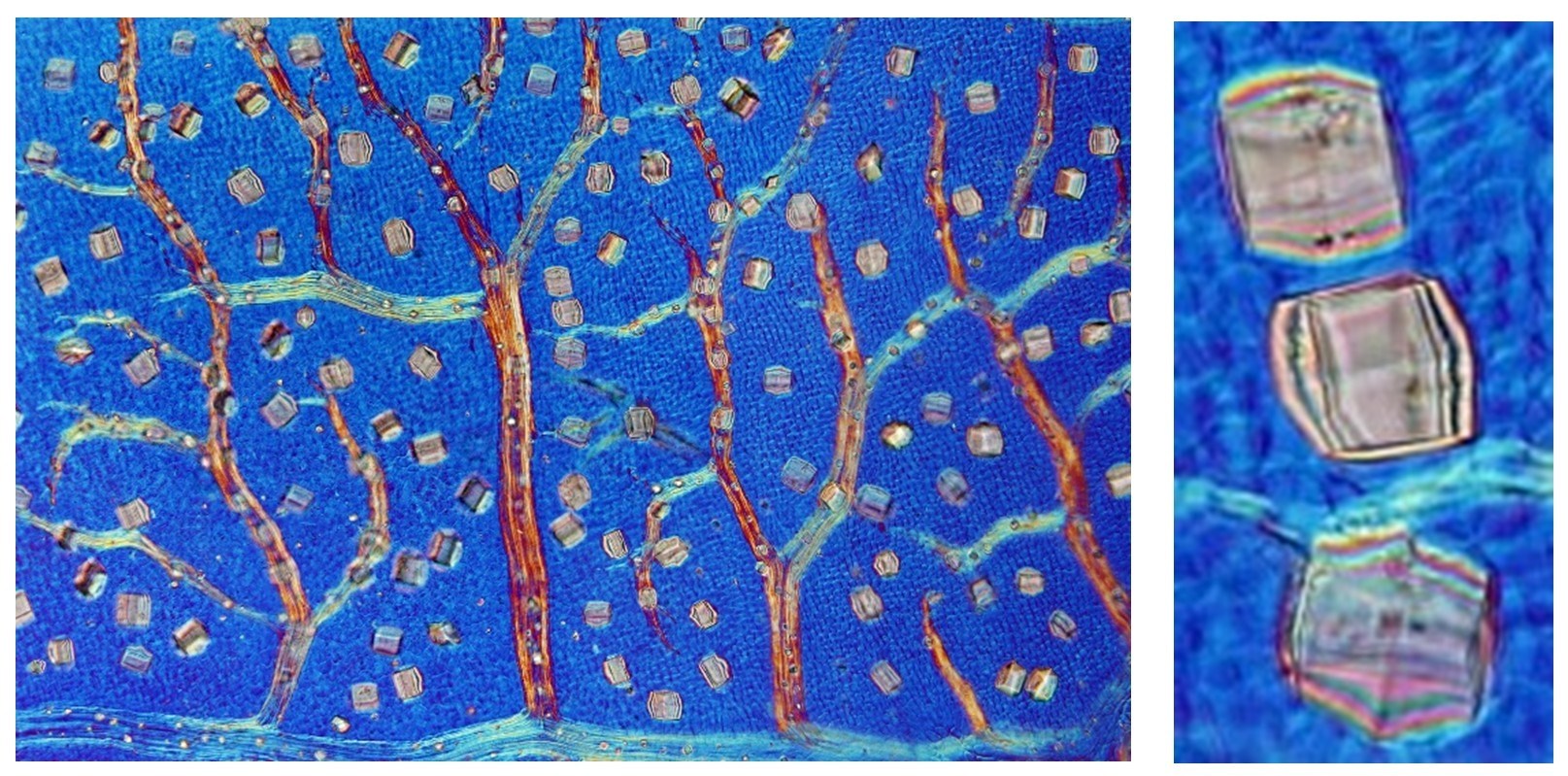

Cropping is here to stay, but what to do with all those pixels? We’re covering our entire existence with cameras, and at the same time moving beyond the representational exactitude of subjects that additional resolution has made possible. We are stretching those limits of visibility, with telescopes, with microscopes and with the peripatetic drone, all contributing to a vast new wealth of images that can be cropped in multiple, often artistic ways, like this storm on Jupiter.

It may also be the power of look-alikes that will seize our fancy. The folds in that violent weather pattern millions of miles away look uncannily like the folds of a heavy garment that might have been drawn by a Renaissance artist such as Leonardo or Dürer, or the work of some modern abstract painter with a definitive style. There are more look-alikes to be discovered as the photographic opportunities multiply. When a forest in a snowstorm turns out to be a witch hazel leaf producing defensive crystals, we have a point of reference to apply to an alien subject beyond the naked eye. And when the invisible is made visible, as it is in photomicrography, we can keep on cropping, down to the crystals themselves and their resemblance to squares of candy. Nothing under the sun is not like something else.

As we crop our way into the tiniest corners of our universe, we can throw away the magnifying glass. We’ve found a way to liberate the moments from the hours, in a visual sense. The humble cropping tool is not sexy. Its practicality precludes the charisma bestowed on other photographic helpers such as lenses and filters. But because it is inexorably linked to the way we see, living without it—now that we have it—is unimaginable. And before we hit the ground like that fool in the little masterpiece, we should make good use of it.

* * *

Many thanks to Leanne Ogasawara for the little masterpiece that launched a flurry of words.