Eric Drexler at AI Prospects:

What we’re building today is not “an AI” that might cooperate or rebel, but an expanding capacity to design, develop, produce, deploy, and adapt complex systems at scale—the basis for a hypercapable world. Taking this prospect seriously changes what to expect and what we can do.

What we’re building today is not “an AI” that might cooperate or rebel, but an expanding capacity to design, develop, produce, deploy, and adapt complex systems at scale—the basis for a hypercapable world. Taking this prospect seriously changes what to expect and what we can do.

Over these two years, AI development has continued to move in this direction. Compound, multi-component AI systems have become dominant. Orchestration has emerged as central. “Agentic” workflows organize task-focused behavior rather than autonomous goal-pursuit. The framing of intelligence as a malleable resource increasingly reflects how practitioners discuss their work. The framework I’ve outlined anticipated this direction, and developments align with the logic it describes.

What follows is both a retrospective and a synthesis—a map of terrain for new readers, a clarified conceptual architecture for those who followed piece by piece. The focus is conditional analysis and strategic preparation, not prediction and speculation. Predictions and odds are for spectators; participants weigh options.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

When Katherine Dunn

When Katherine Dunn Unlike earlier protest waves, this unrest unfolds as Iran’s core pillars—its economic viability, coercive capacity, and external deterrence—fail simultaneously, creating a systemic crisis the regime has never faced and may not survive.

Unlike earlier protest waves, this unrest unfolds as Iran’s core pillars—its economic viability, coercive capacity, and external deterrence—fail simultaneously, creating a systemic crisis the regime has never faced and may not survive. What conditions did Brodkey observe? That already in 1992, “the old American middle class is gone,” its scattered remaining members defined only by participation in such institutions as the stock market, the tax system and “an interlocking web of universities.” Most of them live in isolated suburbs, which “do not and cannot do much to preserve culture or the interplay of groups and classes that heretofore made up American education in politics, in American political realities.” Due to the consequent loss of “political and social ballast,” awareness of local reality has given way to the seductiveness of mass fantasy. “Moral issues are complex and tangled. The jury system argues tacitly that all issues are arguable. And they are. And that time changes things. And it does. That adjudication and rights and duties are complex matters.” Common sense, but also “almost all culture, literature, history, philosophy, even religion, if studied and pondered, tell us that. The disappearance of common sense and the ebbing of culture and the advance of the dreamed-of and dreamlike are clear signs of social danger.”

What conditions did Brodkey observe? That already in 1992, “the old American middle class is gone,” its scattered remaining members defined only by participation in such institutions as the stock market, the tax system and “an interlocking web of universities.” Most of them live in isolated suburbs, which “do not and cannot do much to preserve culture or the interplay of groups and classes that heretofore made up American education in politics, in American political realities.” Due to the consequent loss of “political and social ballast,” awareness of local reality has given way to the seductiveness of mass fantasy. “Moral issues are complex and tangled. The jury system argues tacitly that all issues are arguable. And they are. And that time changes things. And it does. That adjudication and rights and duties are complex matters.” Common sense, but also “almost all culture, literature, history, philosophy, even religion, if studied and pondered, tell us that. The disappearance of common sense and the ebbing of culture and the advance of the dreamed-of and dreamlike are clear signs of social danger.” If you read a book

If you read a book In the early 1990s, a groundswell of young women raised on second-wave feminism but marginalized within the supposedly progressive realm of punk music rose up to make themselves heard, in a movement known as riot grrrl. Bands like

In the early 1990s, a groundswell of young women raised on second-wave feminism but marginalized within the supposedly progressive realm of punk music rose up to make themselves heard, in a movement known as riot grrrl. Bands like  Dr. Franz Kafka, as he is officially listed, is buried in Prague’s New Jewish Cemetery, about a mile down the road from where I live in the neighbourhood of Žižkov. The greater Olšany Cemetery, which it adjoins, is across the street from my apartment. I often go there for walks in the evening, meandering along its overgrown rows and flower-crowded graves. Kafka’s headstone looks like an expressionist prism, a long diamond slightly fattened at its top. The stone bed in front of it is frequently littered with candles, pens, scraps of paper, rocks painted with pictures of beetles. He is interred there along with his mother Julie and his father Hermann (whom he is unable to escape even in death). Max Brod, without whom we’d know nothing of Kafka, has a plaque on the opposite wall. Given that Kafka instructed Brod to burn all of his work “unread,” he almost certainly would not have welcomed people flocking to his grave, so whenever I stop by to say hello to him, I think to myself: “He would hate this.”

Dr. Franz Kafka, as he is officially listed, is buried in Prague’s New Jewish Cemetery, about a mile down the road from where I live in the neighbourhood of Žižkov. The greater Olšany Cemetery, which it adjoins, is across the street from my apartment. I often go there for walks in the evening, meandering along its overgrown rows and flower-crowded graves. Kafka’s headstone looks like an expressionist prism, a long diamond slightly fattened at its top. The stone bed in front of it is frequently littered with candles, pens, scraps of paper, rocks painted with pictures of beetles. He is interred there along with his mother Julie and his father Hermann (whom he is unable to escape even in death). Max Brod, without whom we’d know nothing of Kafka, has a plaque on the opposite wall. Given that Kafka instructed Brod to burn all of his work “unread,” he almost certainly would not have welcomed people flocking to his grave, so whenever I stop by to say hello to him, I think to myself: “He would hate this.” T

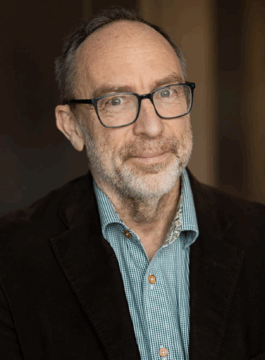

T Jimmy Wales, an Internet entrepreneur from Huntsville, Alabama, now based in London, is best known for creating Wikipedia, which launched in January 2001. The online encyclopedia now holds more than seven million articles and has become a standard guide for anyone seeking information.

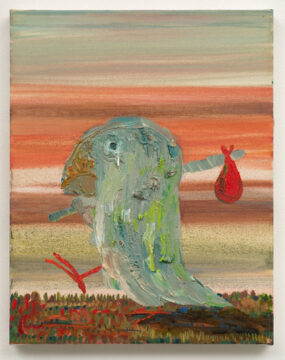

Jimmy Wales, an Internet entrepreneur from Huntsville, Alabama, now based in London, is best known for creating Wikipedia, which launched in January 2001. The online encyclopedia now holds more than seven million articles and has become a standard guide for anyone seeking information. Eisenman has said she started out in a “degenerate and proto-queer” environment, asserting that, when she arrived in New York in the late 1980s, there “was no such thing as queer yet.” The artist wasn’t interested in modernism’s pieties. She was after drama. Her influences include Caravaggio, Giotto, Michelangelo, Grant Wood, Georg Baselitz, and WPA murals, all mixed into clusterfucks of seriousness and stupidity, tenderness and the grotesquerie. Her Alice in Wonderland depicts a tiny Alice whose head is jammed into the vagina of Wonder Woman. She’s created scenes of castration and Betty Rubble and Wilma Flintstone in flagrante ecstasy. Artist Amy Sillman wrote that Eisenman renders figures “with riotous unpredictability, anti-Puritanically taking delight in misbehavior on every level.” Eisenman takes the sacred and drags it across the barroom floor.

Eisenman has said she started out in a “degenerate and proto-queer” environment, asserting that, when she arrived in New York in the late 1980s, there “was no such thing as queer yet.” The artist wasn’t interested in modernism’s pieties. She was after drama. Her influences include Caravaggio, Giotto, Michelangelo, Grant Wood, Georg Baselitz, and WPA murals, all mixed into clusterfucks of seriousness and stupidity, tenderness and the grotesquerie. Her Alice in Wonderland depicts a tiny Alice whose head is jammed into the vagina of Wonder Woman. She’s created scenes of castration and Betty Rubble and Wilma Flintstone in flagrante ecstasy. Artist Amy Sillman wrote that Eisenman renders figures “with riotous unpredictability, anti-Puritanically taking delight in misbehavior on every level.” Eisenman takes the sacred and drags it across the barroom floor. During a week in December when violence seemed to rap on every door, I saw two plays about women who take their lives into their own hands: Hedda Gabler at the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, and Anna Christie at Saint Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn. The plays were written thirty years apart. Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen in 1891, and Anna Christie by Eugene O’Neill in 1921. That year, Alexander Woollcott, reviewing the first production of Anna Christie for the New York Times, wrote, “All grown-up playgoers should jot down in their notebooks the name of Anna Christie as that of a play they really ought to see.” Though O’Neill won the Pulitzer Prize for Anna Christie, the play has been infrequently performed. It is being directed now by Thomas Kail, and Anna is played by his wife, Michelle Williams. On the other hand, Hedda Gabler, directed this time by James Bundy and starring Marianna Gailus, is a warhorse.

During a week in December when violence seemed to rap on every door, I saw two plays about women who take their lives into their own hands: Hedda Gabler at the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, and Anna Christie at Saint Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn. The plays were written thirty years apart. Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen in 1891, and Anna Christie by Eugene O’Neill in 1921. That year, Alexander Woollcott, reviewing the first production of Anna Christie for the New York Times, wrote, “All grown-up playgoers should jot down in their notebooks the name of Anna Christie as that of a play they really ought to see.” Though O’Neill won the Pulitzer Prize for Anna Christie, the play has been infrequently performed. It is being directed now by Thomas Kail, and Anna is played by his wife, Michelle Williams. On the other hand, Hedda Gabler, directed this time by James Bundy and starring Marianna Gailus, is a warhorse. An octopus’s adaptive camouflage has long inspired materials scientists looking to come up with new cloaking technologies. Now researchers have created a

An octopus’s adaptive camouflage has long inspired materials scientists looking to come up with new cloaking technologies. Now researchers have created a  T

T