Traci Watson in Nature:

Every mythology needs a good trickster, and there are few better than the Norse god Loki. He stirs trouble and insults other gods. He is elusive, anarchic and ambiguous. He is, in other words, the perfect namesake for a group of microbes — the Lokiarchaeota — that is rewriting a fundamental story about life’s early roots. These unruly microbes belong to a category of single-celled organisms called archaea, which resemble bacteria under a microscope but are as distinct from them in some respects as humans are. The Lokis, as they are sometimes known, were discovered by sequencing DNA from sea-floor muck collected near Greenland1. Together with some related microbes, they are prodding biologists to reconsider one of the greatest events in the history of life on Earth — the appearance of the eukaryotes, the group of organisms that includes all plants, animals, fungi and more.

Every mythology needs a good trickster, and there are few better than the Norse god Loki. He stirs trouble and insults other gods. He is elusive, anarchic and ambiguous. He is, in other words, the perfect namesake for a group of microbes — the Lokiarchaeota — that is rewriting a fundamental story about life’s early roots. These unruly microbes belong to a category of single-celled organisms called archaea, which resemble bacteria under a microscope but are as distinct from them in some respects as humans are. The Lokis, as they are sometimes known, were discovered by sequencing DNA from sea-floor muck collected near Greenland1. Together with some related microbes, they are prodding biologists to reconsider one of the greatest events in the history of life on Earth — the appearance of the eukaryotes, the group of organisms that includes all plants, animals, fungi and more.

The discovery of archaea in the late 1970s led scientists to propose that the tree of life diverged long ago into three main trunks, or ‘domains’. One trunk gave rise to modern bacteria; one to archaea. And the third produced eukaryotes. But debates soon erupted over the structure of these trunks. A leading ‘three-domain’ model held that archaea and eukaryotes diverged from a common ancestor. But a two-domain scenario suggested that eukaryotes diverged directly from a subgroup of archaea. The arguments, although heated at times, eventually stagnated, says microbiologist Phil Hugenholtz at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia. Then the Lokis and their relatives blew in like “a breath of fresh air”, he says, and revived the case for a two-domain tree.

More here.

Most of us have no trouble telling the difference between a robot and a living, feeling organism. Nevertheless, our brains often treat robots as if they were alive. We give them names, imagine that they have emotions and inner mental states, get mad at them when they do the wrong thing or feel bad for them when they seem to be in distress. Kate Darling is a research at the MIT Media Lab who specializes in social robotics, the interactions between humans and machines. We talk about why we cannot help but anthropomorphize even very non-human-appearing robots, and what that means for legal and social issues now and in the future, including robot companions and helpers in various forms.

Most of us have no trouble telling the difference between a robot and a living, feeling organism. Nevertheless, our brains often treat robots as if they were alive. We give them names, imagine that they have emotions and inner mental states, get mad at them when they do the wrong thing or feel bad for them when they seem to be in distress. Kate Darling is a research at the MIT Media Lab who specializes in social robotics, the interactions between humans and machines. We talk about why we cannot help but anthropomorphize even very non-human-appearing robots, and what that means for legal and social issues now and in the future, including robot companions and helpers in various forms.

WASHINGTON — Barely five months after his son’s death from brain cancer, a bereaved Vice President Joe Biden announced to the nation he would not run for president in 2016 — and immediately pinpointed his deepest regret. “If I could be anything, I would have wanted to be the president that ended cancer,” he said in a Rose Garden address in October 2015. “Because it’s possible.” Biden’s announcement that he will run for president in 2020, however, has resurfaced his dream: a White House that makes cancer a signature issue, backed by a politician whose life was so publicly upended by the disease. With much of the early debate in the Democratic primary centering on health care, Biden’s stint as cancer-advocate-in-chief and orchestrator of the

WASHINGTON — Barely five months after his son’s death from brain cancer, a bereaved Vice President Joe Biden announced to the nation he would not run for president in 2016 — and immediately pinpointed his deepest regret. “If I could be anything, I would have wanted to be the president that ended cancer,” he said in a Rose Garden address in October 2015. “Because it’s possible.” Biden’s announcement that he will run for president in 2020, however, has resurfaced his dream: a White House that makes cancer a signature issue, backed by a politician whose life was so publicly upended by the disease. With much of the early debate in the Democratic primary centering on health care, Biden’s stint as cancer-advocate-in-chief and orchestrator of the

T

T Between 1906 and 1914 hundreds of suffragettes were imprisoned and force-fed in Holloway. They turned their resistance to prison rules into a political programme. Suffragette prisoners were held separately and forbidden from communicating, but if one of them smashed a window to protest against poor air quality, for instance, the others would follow suit. They documented their treatment and smuggled out letters and diaries. The WSPU rented a house nearby, and used it as a base to communicate with the prisoners – and to throw bombs and bottles at the prison. Suffragettes were greeted on release by applauding crowds. The governor resigned. ‘If you are not a rebel before going into Holloway, there is no reason to wonder at your being one when you come out,’ wrote Edith Whitworth, secretary of the Sheffield branch of the WSPU. The imprisonment of middle-class women, which was unusual, helped draw public attention to the treatment of incarcerated women in general, and the suffragettes agitated for improved prison conditions. Davies gives ample attention to their use of Holloway as an icon of struggle: a Holloway flag was waved on suffragette marches; Christmas cards were produced with an illustration of the prison (‘Votes and a Happy Year’); there were Holloway diaries, demonstrations, songs and poems (‘Oh, Holloway, grim Holloway/With grey, forbidding towers!/Stern are the walls, but sterner still/Is woman’s free, unconquered will’).

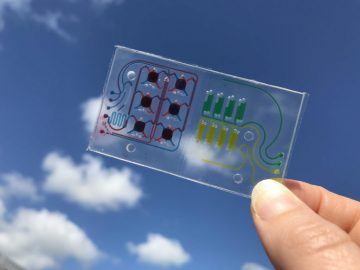

Between 1906 and 1914 hundreds of suffragettes were imprisoned and force-fed in Holloway. They turned their resistance to prison rules into a political programme. Suffragette prisoners were held separately and forbidden from communicating, but if one of them smashed a window to protest against poor air quality, for instance, the others would follow suit. They documented their treatment and smuggled out letters and diaries. The WSPU rented a house nearby, and used it as a base to communicate with the prisoners – and to throw bombs and bottles at the prison. Suffragettes were greeted on release by applauding crowds. The governor resigned. ‘If you are not a rebel before going into Holloway, there is no reason to wonder at your being one when you come out,’ wrote Edith Whitworth, secretary of the Sheffield branch of the WSPU. The imprisonment of middle-class women, which was unusual, helped draw public attention to the treatment of incarcerated women in general, and the suffragettes agitated for improved prison conditions. Davies gives ample attention to their use of Holloway as an icon of struggle: a Holloway flag was waved on suffragette marches; Christmas cards were produced with an illustration of the prison (‘Votes and a Happy Year’); there were Holloway diaries, demonstrations, songs and poems (‘Oh, Holloway, grim Holloway/With grey, forbidding towers!/Stern are the walls, but sterner still/Is woman’s free, unconquered will’). An unusual bit of cargo was aboard the latest Space X mission to restock the International Space Station with essential supplies in the early hours of Saturday morning. Usually, these SpaceX launches carry clothes or equipment that astronauts aboard the ISS may need to fix minor issues. But this latest launch also included tiny structures — about as big as a USB drive — containing human cells and known colloquially known as “organs on chips” were launched into space as part of a new experimental program from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. These tissue chips are designed, with the help of pumps and other fluidics, to mimic the function of an organ. They’re used to study a wide range of diseases as well as test potential treatments. Most of the experiments with tissue chips have been confined to Earth. But in December, the first of five teams funded by the NCATS program launched an organ chip containing immune cells into space. The chips from the four other teams — roughly 50 chips in total — were packed into shoebox-sized boxes, along with all the material to help keep them going and sent along on a space capsule called Dragon. And if all goes to plan, the ISS will capture the capsule this morning. Over the next few weeks, the teams behind these tissue chips are hoping to learn all about what space — specifically, microgravity in space — does to human cells. I chatted with Lucie Low, the program manager of

An unusual bit of cargo was aboard the latest Space X mission to restock the International Space Station with essential supplies in the early hours of Saturday morning. Usually, these SpaceX launches carry clothes or equipment that astronauts aboard the ISS may need to fix minor issues. But this latest launch also included tiny structures — about as big as a USB drive — containing human cells and known colloquially known as “organs on chips” were launched into space as part of a new experimental program from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. These tissue chips are designed, with the help of pumps and other fluidics, to mimic the function of an organ. They’re used to study a wide range of diseases as well as test potential treatments. Most of the experiments with tissue chips have been confined to Earth. But in December, the first of five teams funded by the NCATS program launched an organ chip containing immune cells into space. The chips from the four other teams — roughly 50 chips in total — were packed into shoebox-sized boxes, along with all the material to help keep them going and sent along on a space capsule called Dragon. And if all goes to plan, the ISS will capture the capsule this morning. Over the next few weeks, the teams behind these tissue chips are hoping to learn all about what space — specifically, microgravity in space — does to human cells. I chatted with Lucie Low, the program manager of

The more general critiques take up larger intellectual currents in the eighteenth century. The era’s systematic forays into physical anthropology and human classification laid the foundation for the noxious race science that emerged in the nineteenth century. So did the rise of materialism: it became harder to argue that our varying physical carapaces housed equivalent souls implanted by God. A heedless sense of universalism, in turn, might encourage the thought that the more advanced civilizations were merely lifting up those more backward when they conquered and colonized them.

The more general critiques take up larger intellectual currents in the eighteenth century. The era’s systematic forays into physical anthropology and human classification laid the foundation for the noxious race science that emerged in the nineteenth century. So did the rise of materialism: it became harder to argue that our varying physical carapaces housed equivalent souls implanted by God. A heedless sense of universalism, in turn, might encourage the thought that the more advanced civilizations were merely lifting up those more backward when they conquered and colonized them. Feynman was born 100 years ago May 11. It’s an anniversary inspiring much celebration in the physics world. Feynman was one of the last great physicist celebrities, universally acknowledged as a genius who stood out even from other geniuses.

Feynman was born 100 years ago May 11. It’s an anniversary inspiring much celebration in the physics world. Feynman was one of the last great physicist celebrities, universally acknowledged as a genius who stood out even from other geniuses.

The title of this essay may sound redundant: aren’t all Stoics unemotional, making it their business to go through life with a stiff upper lip? Actually, no, and neither was Marcus, whose 1,898th birthday falls on April 26th of this year. It is true that he wrote in the Meditations, his personal philosophical diary: ‘When you have savouries and fine dishes set before you, you will gain an idea of their nature if you tell yourself that this is the corpse of a fish, and that the corpse of a bird or a pig; or again, that fine Falernian wine is merely grape-juice, and this purple robe some sheep’s wool dipped in the blood of a shellfish; and as for sexual intercourse, it is the friction of a piece of gut and, following a sort of convulsion, the expulsion of mucus.’ (VI.13)

The title of this essay may sound redundant: aren’t all Stoics unemotional, making it their business to go through life with a stiff upper lip? Actually, no, and neither was Marcus, whose 1,898th birthday falls on April 26th of this year. It is true that he wrote in the Meditations, his personal philosophical diary: ‘When you have savouries and fine dishes set before you, you will gain an idea of their nature if you tell yourself that this is the corpse of a fish, and that the corpse of a bird or a pig; or again, that fine Falernian wine is merely grape-juice, and this purple robe some sheep’s wool dipped in the blood of a shellfish; and as for sexual intercourse, it is the friction of a piece of gut and, following a sort of convulsion, the expulsion of mucus.’ (VI.13)