Helen Santoro in Science:

Plastic makes up nearly 70% of all ocean litter, putting countless aquatic species at risk. But there is a tiny bit of hope—a teeny, tiny one to be precise: Scientists have discovered that microscopic marine microbes are eating away at the plastic, causing trash to slowly break down.

Plastic makes up nearly 70% of all ocean litter, putting countless aquatic species at risk. But there is a tiny bit of hope—a teeny, tiny one to be precise: Scientists have discovered that microscopic marine microbes are eating away at the plastic, causing trash to slowly break down.

To conduct the study, researchers collected weathered plastic from two different beaches in Chania, Greece. The litter had already been exposed to the sun and undergone chemical changes that caused it to become more brittle, all of which needs to happen before the microbes start to munch on the plastic. The pieces were either polyethylene, the most popular plastic and the one found in products such as grocery bags and shampoo bottles, or polystyrene, a hard plastic found in food packaging and electronics. The team immersed both in saltwater with either naturally occurring ocean microbes or engineered microbes that were enhanced with carbon-eating microbe strains and could survive solely off of the carbon in plastic. Scientists then analyzed changes in the materials over a period of 5 months.

Both types of plastic lost a significant amount of weight after being exposed to the natural and engineered microbes, scientists reported in April in the Journal of Hazardous Materials. The microbes further changed the chemical makeup of the material, causing the polyethylene’s weight to go down by 7% and the polystyrene’s weight to go down by 11%. These findings may offer a new strategy to help combat ocean pollution: Deploy marine microbes to eat up the trash. However, researchers still need to measure how effective these microbes would be on a global scale.

More here.

It’s amazing that this landmark symphony could have been so easily forgotten. As with the other seminal New Englanders—George Whitefield Chadwick, Horatio Parker, and Edward MacDowell, among them—modernism killed off Paine’s music. And with the ascendancy of American vernacular forms, reflected in the music of Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and others, any music arising from the German Romantic tradition could be ridiculed and ignored. Paine may have been the acknowledged dean of a New England school, but he could not be comfortably located with any American school. Even Paine’s student Richard Aldrich, writing in the early 20th century, argued that Paine’s music, despite its “fertility,” “genuine warmth,” “spontaneity of invention,” and “fine harmonic feeling,” did not “disclose ‘American’ characteristics.” But what in Paine’s time and cultural milieu would have constituted an American characteristic?

It’s amazing that this landmark symphony could have been so easily forgotten. As with the other seminal New Englanders—George Whitefield Chadwick, Horatio Parker, and Edward MacDowell, among them—modernism killed off Paine’s music. And with the ascendancy of American vernacular forms, reflected in the music of Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and others, any music arising from the German Romantic tradition could be ridiculed and ignored. Paine may have been the acknowledged dean of a New England school, but he could not be comfortably located with any American school. Even Paine’s student Richard Aldrich, writing in the early 20th century, argued that Paine’s music, despite its “fertility,” “genuine warmth,” “spontaneity of invention,” and “fine harmonic feeling,” did not “disclose ‘American’ characteristics.” But what in Paine’s time and cultural milieu would have constituted an American characteristic? Somehow I became respectable. I don’t know how—the last film I directed got some terrible reviews and was rated NC-17. Six people in my personal phone book have been sentenced to life in prison. I did an art piece called Twelve Assholes and a Dirty Foot, which is composed of close-ups from porn films, yet a museum now has it in their permanent collection and nobody got mad. What the hell has happened?

Somehow I became respectable. I don’t know how—the last film I directed got some terrible reviews and was rated NC-17. Six people in my personal phone book have been sentenced to life in prison. I did an art piece called Twelve Assholes and a Dirty Foot, which is composed of close-ups from porn films, yet a museum now has it in their permanent collection and nobody got mad. What the hell has happened? There is a lot of horror in this book. People are thrown from helicopters into the sea, their arms tied behind their backs. A colonel grinds up his victims’ bodies and feeds them to his dogs. Forché finds mutilated corpses by the side of the road. She visits a prison where men are kept in cages the size of washing machines. She and a friend are pursued by an escuadrón de la muerte (death squad). Later, she meets a man who was a member of one such squad, who recalls the sound of bubbles as he cut his victims’ throats.

There is a lot of horror in this book. People are thrown from helicopters into the sea, their arms tied behind their backs. A colonel grinds up his victims’ bodies and feeds them to his dogs. Forché finds mutilated corpses by the side of the road. She visits a prison where men are kept in cages the size of washing machines. She and a friend are pursued by an escuadrón de la muerte (death squad). Later, she meets a man who was a member of one such squad, who recalls the sound of bubbles as he cut his victims’ throats. Why do we like what we like? The books, movies, photos, and artworks that form our perspective—who puts them in front of us? One answer is the critic, that cipher of taste who places art in its various corridors, then augments, defines, degrades, and ultimately shapes the works that shape us. In times when the public’s eye travels with ever more scope but not necessarily more depth, criticism, the act of choosing—and so much more—becomes more important than ever. It’s for this reason that so many eyes are turning to Parul Sehgal and Teju Cole, two critics—as well as editors, essayists, and artists—challenging not only us but art forms themselves.

Why do we like what we like? The books, movies, photos, and artworks that form our perspective—who puts them in front of us? One answer is the critic, that cipher of taste who places art in its various corridors, then augments, defines, degrades, and ultimately shapes the works that shape us. In times when the public’s eye travels with ever more scope but not necessarily more depth, criticism, the act of choosing—and so much more—becomes more important than ever. It’s for this reason that so many eyes are turning to Parul Sehgal and Teju Cole, two critics—as well as editors, essayists, and artists—challenging not only us but art forms themselves. Most people in the modern world — and the vast majority of Mindscape listeners, I would imagine — agree that humans are part of the animal kingdom, and that all living animals evolved from a common ancestor. Nevertheless, there are ways in which we are unique; humans are the only animals that stress out over Game of Thrones (as far as I know). I talk with geneticist and science writer Adam Rutherford about what makes us human, and how we got that way, both biologically and culturally. One big takeaway lesson is that it’s harder to find firm distinctions than you might think; animals use language and tools and fire, and have way more inventive sex lives than we do.

Most people in the modern world — and the vast majority of Mindscape listeners, I would imagine — agree that humans are part of the animal kingdom, and that all living animals evolved from a common ancestor. Nevertheless, there are ways in which we are unique; humans are the only animals that stress out over Game of Thrones (as far as I know). I talk with geneticist and science writer Adam Rutherford about what makes us human, and how we got that way, both biologically and culturally. One big takeaway lesson is that it’s harder to find firm distinctions than you might think; animals use language and tools and fire, and have way more inventive sex lives than we do. Earlier this year, the presidents of Sudan and Algeria both announced they would step aside

Earlier this year, the presidents of Sudan and Algeria both announced they would step aside  A

A  Scientists have created a living organism whose DNA is entirely human-made — perhaps a new form of life, experts said, and a milestone in the field of synthetic biology. Researchers at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Britain reported on Wednesday that they had rewritten the DNA of the bacteria Escherichia coli, fashioning a synthetic genome four times larger and far more complex than any previously created. The bacteria are alive, though unusually shaped and reproducing slowly. But their cells operate according to a new set of biological rules, producing familiar proteins with a reconstructed genetic code. The achievement one day may lead to organisms that produce novel medicines or other valuable molecules, as living factories. These synthetic bacteria also may offer clues as to how the genetic code arose in the early history of life.

Scientists have created a living organism whose DNA is entirely human-made — perhaps a new form of life, experts said, and a milestone in the field of synthetic biology. Researchers at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Britain reported on Wednesday that they had rewritten the DNA of the bacteria Escherichia coli, fashioning a synthetic genome four times larger and far more complex than any previously created. The bacteria are alive, though unusually shaped and reproducing slowly. But their cells operate according to a new set of biological rules, producing familiar proteins with a reconstructed genetic code. The achievement one day may lead to organisms that produce novel medicines or other valuable molecules, as living factories. These synthetic bacteria also may offer clues as to how the genetic code arose in the early history of life. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have gone on so long that the Middle East war novel has itself become a crusty genre — a familiar set of echoes coming back to us from ravaged lands. Many of these books are stirring on the level of detail but an equal number thoughtlessly valorize the American soldier or wallow in the morally vacuous conclusion that war is hell and that’s that. Where is the ferocious “Catch-22” of these benighted conflicts? Who will have the temerity to make these wars the subject of bracing comedy?

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have gone on so long that the Middle East war novel has itself become a crusty genre — a familiar set of echoes coming back to us from ravaged lands. Many of these books are stirring on the level of detail but an equal number thoughtlessly valorize the American soldier or wallow in the morally vacuous conclusion that war is hell and that’s that. Where is the ferocious “Catch-22” of these benighted conflicts? Who will have the temerity to make these wars the subject of bracing comedy? Jared Diamond’s new book,

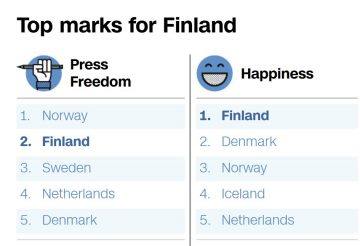

Jared Diamond’s new book,  On a recent afternoon in Helsinki, a group of students gathered to hear a lecture on a subject that is far from a staple in most community college curriculums.

On a recent afternoon in Helsinki, a group of students gathered to hear a lecture on a subject that is far from a staple in most community college curriculums. This January, Hussein Fancy, an American academic of Pakistani origin, received the Herbert Baxter Adams Prize, awarded annually by the American Historical Association “to honor a distinguished book published in English in the field of European history,” for his groundbreaking work The Mercenary Mediterranean: Sovereignty, Religion, and Violence in the Medieval Crown of Aragon. This isn’t the first prize awarded to this book: it had earlier been the recipient of the Jans F. Verbruggen Prize from De Re Militari for the best book in medieval military history and the L. Carl Brown AIMS Book Prize in North African Studies. These three very different prizes, each with different parameters, indicate the range and importance of Fancy’s research.

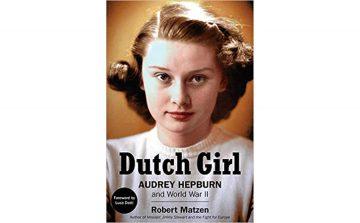

This January, Hussein Fancy, an American academic of Pakistani origin, received the Herbert Baxter Adams Prize, awarded annually by the American Historical Association “to honor a distinguished book published in English in the field of European history,” for his groundbreaking work The Mercenary Mediterranean: Sovereignty, Religion, and Violence in the Medieval Crown of Aragon. This isn’t the first prize awarded to this book: it had earlier been the recipient of the Jans F. Verbruggen Prize from De Re Militari for the best book in medieval military history and the L. Carl Brown AIMS Book Prize in North African Studies. These three very different prizes, each with different parameters, indicate the range and importance of Fancy’s research. Audrey Hepburn was one of the most celebrated actresses of the 20th century and a winner of Academy, Tony, Grammy, and Emmy awards. She was a style icon and, in later life, a tireless humanitarian who worked to improve conditions for children in some of the poorest communities in Africa and Asia as an ambassador for UNICEF. But this extraordinary individual was the product of an extremely difficult childhood. Her father was a British subject and something of a rake and her mother was a minor Dutch noblewoman. Both of her parents flirted with the Nazis in the 1930s. Her mother met Adolf Hitler and wrote favorable articles about him for the British Union of Fascists. After abandoning the family in 1935, her father moved to England and became so active with Oswald Mosley’s fascists that he was interned during World War II. As a child, Hepburn rarely saw him.

Audrey Hepburn was one of the most celebrated actresses of the 20th century and a winner of Academy, Tony, Grammy, and Emmy awards. She was a style icon and, in later life, a tireless humanitarian who worked to improve conditions for children in some of the poorest communities in Africa and Asia as an ambassador for UNICEF. But this extraordinary individual was the product of an extremely difficult childhood. Her father was a British subject and something of a rake and her mother was a minor Dutch noblewoman. Both of her parents flirted with the Nazis in the 1930s. Her mother met Adolf Hitler and wrote favorable articles about him for the British Union of Fascists. After abandoning the family in 1935, her father moved to England and became so active with Oswald Mosley’s fascists that he was interned during World War II. As a child, Hepburn rarely saw him.