Andrew Doyle in Spiked:

Critics are often maligned. Kenneth Williams memorably compared them to eunuchs in a harem: ‘They’re there every night. They see it done every night. But they can’t do it themselves.’ It’s difficult not to enjoy the barbed wit of Williams, even when he’s indulging in this kind of unfair generalisation. Criticism, if done well, is an art form in and of itself – but now that clickbait is prioritised over insight the standards have undeniably dropped.

Critics are often maligned. Kenneth Williams memorably compared them to eunuchs in a harem: ‘They’re there every night. They see it done every night. But they can’t do it themselves.’ It’s difficult not to enjoy the barbed wit of Williams, even when he’s indulging in this kind of unfair generalisation. Criticism, if done well, is an art form in and of itself – but now that clickbait is prioritised over insight the standards have undeniably dropped.

It would appear that the infection of identity politics has spread from the creatives to the critics. Praise for Christopher Nolan’s film Dunkirk was offset by those who complained that he had not included a sufficiently diverse cast, in spite of the historical fact that the overwhelming majority of those evacuated were young white men. It seems to me that if your initial reaction to a work as arresting as Dunkirk is to appraise the degree to which its auteur has fulfilled diversity quotas, then you are not well equipped to judge his artistry.

That is not to say that total objectivity is either possible or desirable when it comes to criticism. But the best critics are able to appreciate a piece of work on its own terms, whereas the worst seem to believe that success should be measured on the basis of how closely the artist reflects their own ideological perspective.

More here.

What year is it? It’s 2019, obviously. An easy question. Last year was 2018. Next year will be 2020. We are confident that a century ago it was 1919, and in 1,000 years it will be 3019, if there is anyone left to name it. All of us are fluent with these years; we, and most of the world, use them without thinking. They are ubiquitous. As a child I used to line up my pennies by year of minting, and now I carefully note dates of publication in my scholarly articles.

What year is it? It’s 2019, obviously. An easy question. Last year was 2018. Next year will be 2020. We are confident that a century ago it was 1919, and in 1,000 years it will be 3019, if there is anyone left to name it. All of us are fluent with these years; we, and most of the world, use them without thinking. They are ubiquitous. As a child I used to line up my pennies by year of minting, and now I carefully note dates of publication in my scholarly articles. The tech giants are facing a moment of reckoning. Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Uber all grew explosively over the last decade, in part by delivering real convenience and benefits to consumers. For this we forgave their more venial sins, such as unfair competition, copyright infringement, data hoarding, and price discrimination. But recent years have brought one revelation after another around privacy issues—including Facebook’s sharing of data with the dark arts firm Cambridge Analytica—and ever-growing worries about the tech giants’ monopoly powers.

The tech giants are facing a moment of reckoning. Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Uber all grew explosively over the last decade, in part by delivering real convenience and benefits to consumers. For this we forgave their more venial sins, such as unfair competition, copyright infringement, data hoarding, and price discrimination. But recent years have brought one revelation after another around privacy issues—including Facebook’s sharing of data with the dark arts firm Cambridge Analytica—and ever-growing worries about the tech giants’ monopoly powers. The president of Ukraine sits in his office, a glum look on his face. He has just been trounced in the election by a political outsider, and isn’t taking it well. When his successor, Vasyl Holoborodko, tries to move into his office, the outgoing president shoots at him through the door with a shotgun, just missing his target. He’s refusing to leave until his demands are met, says an aide: he wants a litre of vodka, several packs of cigarettes and political asylum in Yugoslavia. “But Yugoslavia doesn’t even exist anymore,” says Holoborodko. “He knows, that’s why he asked for the vodka,” the aide replies.

The president of Ukraine sits in his office, a glum look on his face. He has just been trounced in the election by a political outsider, and isn’t taking it well. When his successor, Vasyl Holoborodko, tries to move into his office, the outgoing president shoots at him through the door with a shotgun, just missing his target. He’s refusing to leave until his demands are met, says an aide: he wants a litre of vodka, several packs of cigarettes and political asylum in Yugoslavia. “But Yugoslavia doesn’t even exist anymore,” says Holoborodko. “He knows, that’s why he asked for the vodka,” the aide replies. T

T The portrait of university life offered by the online journal Quillette is not a flattering one. Free speech stifled at every turn. Scholars with divergent views relentlessly mobbed. Entire disciplines ruined by left-wing activism. A leafy dystopia populated by irrationally furious undergraduates, pathetically craven administrators, and professors who peddle mindless ideology at the expense of scientific inquiry. It’s enough to make anyone question the mental health of the academy, if not run screaming through the quad.

The portrait of university life offered by the online journal Quillette is not a flattering one. Free speech stifled at every turn. Scholars with divergent views relentlessly mobbed. Entire disciplines ruined by left-wing activism. A leafy dystopia populated by irrationally furious undergraduates, pathetically craven administrators, and professors who peddle mindless ideology at the expense of scientific inquiry. It’s enough to make anyone question the mental health of the academy, if not run screaming through the quad. As the prospects for a nuclear renaissance in the U.S. based on conventional nuclear technology have dimmed, many nuclear advocates have pinned their hopes on advanced reactors that are smaller and utilize different technologies.

As the prospects for a nuclear renaissance in the U.S. based on conventional nuclear technology have dimmed, many nuclear advocates have pinned their hopes on advanced reactors that are smaller and utilize different technologies. Right-wing populists have won an unprecedented 57 seats in elections to the European Union’s Parliament, up from 30 in 2014. In Hungary, Viktor Orban’s Fidesz won a majority of 52 percent. In Italy, Matteo Salvini’s Lega topped the poll at 30 percent, in Britain, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party won, while in France, Marine Le Pen pipped Emmanuel Macron 23 percent to 22 percent. While not quite the populist surge some feared, right-populist momentum continues. Meanwhile, the mainstream Social Democrats and Christian Democrats saw their combined total drop below a majority for the first time, from 56 percent in 2014 to 44 percent as Green and Liberal alternatives gained.

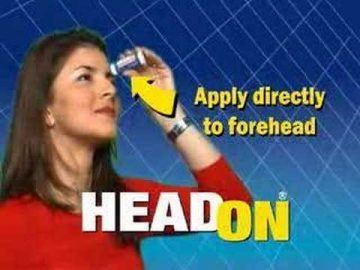

Right-wing populists have won an unprecedented 57 seats in elections to the European Union’s Parliament, up from 30 in 2014. In Hungary, Viktor Orban’s Fidesz won a majority of 52 percent. In Italy, Matteo Salvini’s Lega topped the poll at 30 percent, in Britain, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party won, while in France, Marine Le Pen pipped Emmanuel Macron 23 percent to 22 percent. While not quite the populist surge some feared, right-populist momentum continues. Meanwhile, the mainstream Social Democrats and Christian Democrats saw their combined total drop below a majority for the first time, from 56 percent in 2014 to 44 percent as Green and Liberal alternatives gained. HeadOn was the Max Headroom Incident of the millennial generation. Every time I bring it up, people tell me that they were equally stunned the first time they saw it, and that they remember being so relieved when other people said that they had seen it, too. Companies from Geico to Old Spice to Skittles have all tried their hand at absurdist advertisements, but nothing they’ve produced even remotely achieves the eldritch creepiness of catching the Head On commercial while watching the Weather Channel at 2 a.m. in 2006.

HeadOn was the Max Headroom Incident of the millennial generation. Every time I bring it up, people tell me that they were equally stunned the first time they saw it, and that they remember being so relieved when other people said that they had seen it, too. Companies from Geico to Old Spice to Skittles have all tried their hand at absurdist advertisements, but nothing they’ve produced even remotely achieves the eldritch creepiness of catching the Head On commercial while watching the Weather Channel at 2 a.m. in 2006. In big cities particularly, I notice that every new person I meet is manically interested in what I do, and how much of it. I used to be embarrassed by my lack of drive and murmur vaguely about projects and deadlines, but I’m quite happy now to admit the truth, which is that I have very little ambition and no desire to work any harder than I do now, which is honestly not very much. I’ve calculated fairly minutely how much work I need to do to in order to pay my bills and that’s the amount of work I do. No more. Sometimes I get it wrong and need to work much more than usual for a month or two, sometimes I have blissful unexpected mostly vacant weeks. I work about half as much as I did in Ireland, and earn about half as much money – which is fine with me because I’ve started seeing money not as a mark of achievement but as a cumulative display of all the days you’ve spent not doing what you’d like to be doing. I want freedom, not houses. I’d like more money, certainly, but not enough to give up all my time.

In big cities particularly, I notice that every new person I meet is manically interested in what I do, and how much of it. I used to be embarrassed by my lack of drive and murmur vaguely about projects and deadlines, but I’m quite happy now to admit the truth, which is that I have very little ambition and no desire to work any harder than I do now, which is honestly not very much. I’ve calculated fairly minutely how much work I need to do to in order to pay my bills and that’s the amount of work I do. No more. Sometimes I get it wrong and need to work much more than usual for a month or two, sometimes I have blissful unexpected mostly vacant weeks. I work about half as much as I did in Ireland, and earn about half as much money – which is fine with me because I’ve started seeing money not as a mark of achievement but as a cumulative display of all the days you’ve spent not doing what you’d like to be doing. I want freedom, not houses. I’d like more money, certainly, but not enough to give up all my time. When it comes to intelligence, we all have bad days. Heck, we even have many bad moments, such as when we forget our car keys, forget a friend’s name, or bomb an important test that we’ve taken a day after staying up all night worrying about it. Truth is, none of us– including the world’s smartest human– is perfectly consistent in our cognitive functioning. Sometimes we are at our very best and feel like our brain is on fire, and at other times, we don’t even recognize ourselves. All of this sounds so obvious, but surprisingly the field of human intelligence has not had much to say on the topic. For over the past 120 years, the field has shed far more light on how we differ from each other in our patterns of cognitive functioning than how we each differ within ourselves over time.

When it comes to intelligence, we all have bad days. Heck, we even have many bad moments, such as when we forget our car keys, forget a friend’s name, or bomb an important test that we’ve taken a day after staying up all night worrying about it. Truth is, none of us– including the world’s smartest human– is perfectly consistent in our cognitive functioning. Sometimes we are at our very best and feel like our brain is on fire, and at other times, we don’t even recognize ourselves. All of this sounds so obvious, but surprisingly the field of human intelligence has not had much to say on the topic. For over the past 120 years, the field has shed far more light on how we differ from each other in our patterns of cognitive functioning than how we each differ within ourselves over time. If we’re the kind of people who care both about not being racist, and also about basing our beliefs on the evidence that we have, then the world presents us with a challenge. The world is pretty racist. It shouldn’t be surprising then that sometimes it seems as if the evidence is stacked in favour of some racist belief. For example, it’s racist to assume that someone’s a staff member on the basis of his skin colour. But what if it’s the case that, because of historical patterns of discrimination, the members of staff with whom you interact are predominantly of one race? When the late John Hope Franklin, professor of history at Duke University in North Carolina, hosted a dinner party at his private club in Washington, DC in 1995, he was mistaken as a member of staff. Did the woman who did so do something wrong?

If we’re the kind of people who care both about not being racist, and also about basing our beliefs on the evidence that we have, then the world presents us with a challenge. The world is pretty racist. It shouldn’t be surprising then that sometimes it seems as if the evidence is stacked in favour of some racist belief. For example, it’s racist to assume that someone’s a staff member on the basis of his skin colour. But what if it’s the case that, because of historical patterns of discrimination, the members of staff with whom you interact are predominantly of one race? When the late John Hope Franklin, professor of history at Duke University in North Carolina, hosted a dinner party at his private club in Washington, DC in 1995, he was mistaken as a member of staff. Did the woman who did so do something wrong?  If you’re bad, we are taught, you go to Hell. Who in the world came up with that idea? Some will answer God, but for the purpose of today’s podcast discussion we’ll put that possibility aside and look into the human origins and history of the idea of the Bad Place. Marq de Villiers is a writer and journalist who has authored a series of non-fiction books, many on science and the environment. In

If you’re bad, we are taught, you go to Hell. Who in the world came up with that idea? Some will answer God, but for the purpose of today’s podcast discussion we’ll put that possibility aside and look into the human origins and history of the idea of the Bad Place. Marq de Villiers is a writer and journalist who has authored a series of non-fiction books, many on science and the environment. In  In Varanasi recently, I took an auto-rickshaw from Godowlia to Assi Ghat. Like everyone else in town, the driver and I began talking politics. The 2019 general election was a week away and Prime Minister Narendra Modi was seeking reelection from Varanasi. The driver was an ardent Modi fan and would hear no criticism of him. He even claimed that demonetisation had punished the corrupt rich. One topic led to another and soon he was loudly praising Nathuram Godse as a patriot – Gandhi deserved no less than a bullet for being a Muslim lover. “You don’t know these people,” he thundered. “Read our history! Only Muslims have killed their own fathers to become kings. Has any Hindu ever done so? Inki jaat hi aisi hai. You too should open your mobile and read on WhatsApp. Kamina Rahul is born of a Muslim and a Christian; Nehru’s grandfather, also Muslim, Mughal. Outsiders all. Modi will teach them!” Fortunately, my destination came before his passion for the topic could escalate further.

In Varanasi recently, I took an auto-rickshaw from Godowlia to Assi Ghat. Like everyone else in town, the driver and I began talking politics. The 2019 general election was a week away and Prime Minister Narendra Modi was seeking reelection from Varanasi. The driver was an ardent Modi fan and would hear no criticism of him. He even claimed that demonetisation had punished the corrupt rich. One topic led to another and soon he was loudly praising Nathuram Godse as a patriot – Gandhi deserved no less than a bullet for being a Muslim lover. “You don’t know these people,” he thundered. “Read our history! Only Muslims have killed their own fathers to become kings. Has any Hindu ever done so? Inki jaat hi aisi hai. You too should open your mobile and read on WhatsApp. Kamina Rahul is born of a Muslim and a Christian; Nehru’s grandfather, also Muslim, Mughal. Outsiders all. Modi will teach them!” Fortunately, my destination came before his passion for the topic could escalate further. I

I The first words to pass between Europeans and Americans (one-sided and confusing as they must have been) were in the sacred language of Islam. Christopher Columbus had hoped to sail to Asia and had prepared to communicate at its great courts in one of the major languages of Eurasian commerce. So when Columbus’s interpreter, a Spanish Jew, spoke to the Taíno of Hispaniola, he did so in Arabic. Not just the language of Islam, but the religion itself likely arrived in America in 1492, more than 20 years before Martin Luther nailed his theses to the door, igniting the Protestant reformation. Moors – African and Arab Muslims – had conquered much of the Iberian peninsula in 711, establishing a Muslim culture that lasted nearly eight centuries. By early 1492, the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella completed the Reconquista, defeating the last of the Muslim kingdoms, Granada. By the end of the century, the Inquisition, which had begun a century earlier, had coerced between 300,000 and 800,000 Muslims (and probably at least 70,000 Jews) to convert to Christianity. Spanish Catholics often suspected these Moriscos or conversos of practising Islam (or Judaism) in secret, and the Inquisition pursued and persecuted them. Some, almost certainly, sailed in Columbus’s crew, carrying Islam in their hearts and minds.

The first words to pass between Europeans and Americans (one-sided and confusing as they must have been) were in the sacred language of Islam. Christopher Columbus had hoped to sail to Asia and had prepared to communicate at its great courts in one of the major languages of Eurasian commerce. So when Columbus’s interpreter, a Spanish Jew, spoke to the Taíno of Hispaniola, he did so in Arabic. Not just the language of Islam, but the religion itself likely arrived in America in 1492, more than 20 years before Martin Luther nailed his theses to the door, igniting the Protestant reformation. Moors – African and Arab Muslims – had conquered much of the Iberian peninsula in 711, establishing a Muslim culture that lasted nearly eight centuries. By early 1492, the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella completed the Reconquista, defeating the last of the Muslim kingdoms, Granada. By the end of the century, the Inquisition, which had begun a century earlier, had coerced between 300,000 and 800,000 Muslims (and probably at least 70,000 Jews) to convert to Christianity. Spanish Catholics often suspected these Moriscos or conversos of practising Islam (or Judaism) in secret, and the Inquisition pursued and persecuted them. Some, almost certainly, sailed in Columbus’s crew, carrying Islam in their hearts and minds.