Matteo Pucciarelli in New Left Review:

Matteo Pucciarelli in New Left Review:

Italy has a new strongman—for many, a new saviour. The effective head of the government in Rome is not the titular Premier, Giuseppe Conte, nor the winner of the last election, Five Stars leader Luigi Di Maio. It is the Minister of the Interior, Matteo Salvini. As if overnight, a hitherto obscure municipal councillor from Milan, long-time militant in the separatist Northern League, has become the most powerful figure in the country. In just five years, a party that was a dilapidated political relic, with 3–4 per cent support in the polls, has become, in his hands, the pivot of Italian—and perhaps European—politics. There is a sense, however, in which the story of this astonishing transformation begins a long way off, not in time but space—in the wars and vast economic disparities that have driven millions of Africans and Asians across the Mediterranean in search of work, freedom and a little well-being, towards an affluent Europe that is ever more ageing, unequal and rancorous.

An otherwise normal February day in 2016 in a holding camp on the Greek-Macedonian border, in the middle of that year’s migrant emergency, offers a sense of this landscape. The hamlet of Idomeni lies among low hills, the jagged Balkans in the distance. Here, the double barbed wire of the government in Skopje attracts less attention than Orbán’s rolls of the same in Hungary, though—matter for guilt for some, merit for others—landing a single country with the consequences of a modern exodus. It is nearly supper-time, and seen from a distance the Greek camp, which holds about ten thousand refugees, is quiet, as if swallowed up in the darkness. But as you get closer, there is a souk and some children dancing to Syrian music.

More here.

Joe Humphreys in The Irish Times:

Joe Humphreys in The Irish Times: Dan Bessner in The New Republic:

Dan Bessner in The New Republic: It’s the question on every cancer patient’s mind: How long have I got? Genomicist

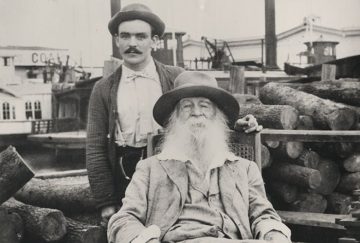

It’s the question on every cancer patient’s mind: How long have I got? Genomicist  “Whitman demonstrates part of his Americanness by placing cocksucking at the center of Leaves of Grass.” Gay liberationist Charles Shively—not one to mince words—wrote this in Calamus Lovers: Walt Whitman’s Working Class Camerados (1987), his revelatory, if sometimes risible, account of the poet’s queer egalitarianism. Whether cocksucking is central to Whitman’s book, or even uniquely American, is debatable; more pertinent is the implied connection between Whitman’s homosexuality and his patriotic fervor.

“Whitman demonstrates part of his Americanness by placing cocksucking at the center of Leaves of Grass.” Gay liberationist Charles Shively—not one to mince words—wrote this in Calamus Lovers: Walt Whitman’s Working Class Camerados (1987), his revelatory, if sometimes risible, account of the poet’s queer egalitarianism. Whether cocksucking is central to Whitman’s book, or even uniquely American, is debatable; more pertinent is the implied connection between Whitman’s homosexuality and his patriotic fervor.

Commentators from across the political spectrum warn us that extreme partisan polarization is dissolving all bases for political cooperation, thereby undermining our democracy. The near total consensus on this point is suspicious. A recent Pew study finds that although citizens want politicians to compromise more, they tend to blame only their political opponents for the deadlock. In calling for conciliation, they seek capitulation from the other side. The warnings about polarization might themselves be displays of polarization.

Commentators from across the political spectrum warn us that extreme partisan polarization is dissolving all bases for political cooperation, thereby undermining our democracy. The near total consensus on this point is suspicious. A recent Pew study finds that although citizens want politicians to compromise more, they tend to blame only their political opponents for the deadlock. In calling for conciliation, they seek capitulation from the other side. The warnings about polarization might themselves be displays of polarization. The movie that made me consider filmmaking, the movie that showed me how a director does what he does, how a director can control a movie through his camera, is Once Upon a Time in the West. It was almost like a film school in a movie. It really illustrated how to make an impact as a filmmaker. How to give your work a signature. I found myself completely fascinated, thinking: ‘That’s how you do it.’ It ended up creating an aesthetic in my mind.

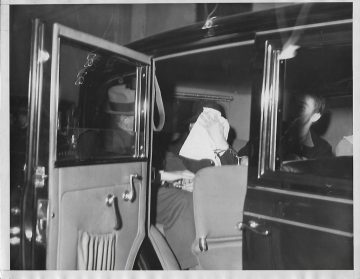

The movie that made me consider filmmaking, the movie that showed me how a director does what he does, how a director can control a movie through his camera, is Once Upon a Time in the West. It was almost like a film school in a movie. It really illustrated how to make an impact as a filmmaker. How to give your work a signature. I found myself completely fascinated, thinking: ‘That’s how you do it.’ It ended up creating an aesthetic in my mind. The press photographer’s task is to obtain a likeness of the person who is at the center of the news. This proves difficult when the subject, who is either accused of crimes or tied, however flimsily, to someone who is, wants to avoid being photographed at all costs. Hounded at every step, unable to escape, even in shackles, the subject resorts to makeshift concealments—hat, sleeve, lapel, handkerchief, newspaper—in order to prevent facial capture. The photographer can only pursue, shadow, perhaps verbally goad the subject, waiting for a slip or a stumble that will cause the mask to drop. When that fails to happen, the photographer’s sole option is to photograph the mask. The public, inflamed by press coverage of the case, wants a face it can charge with blame (and, often enough, spread the blame to faces that bear it a superficial resemblance), but is instead offered a metonym: hat, handkerchief, newspaper. The photographer, in quest of a portrait, has delivered in its place an event: the defeat of portraiture by the subject.

The press photographer’s task is to obtain a likeness of the person who is at the center of the news. This proves difficult when the subject, who is either accused of crimes or tied, however flimsily, to someone who is, wants to avoid being photographed at all costs. Hounded at every step, unable to escape, even in shackles, the subject resorts to makeshift concealments—hat, sleeve, lapel, handkerchief, newspaper—in order to prevent facial capture. The photographer can only pursue, shadow, perhaps verbally goad the subject, waiting for a slip or a stumble that will cause the mask to drop. When that fails to happen, the photographer’s sole option is to photograph the mask. The public, inflamed by press coverage of the case, wants a face it can charge with blame (and, often enough, spread the blame to faces that bear it a superficial resemblance), but is instead offered a metonym: hat, handkerchief, newspaper. The photographer, in quest of a portrait, has delivered in its place an event: the defeat of portraiture by the subject. There is intense debate as to what the outcome tells us about voter support for Brexit, with both Leavers and Remainers claiming vindication. The most striking feature of the results, however, is the polarisation they reveal. The result of a botched Brexit has been the Europeanisation of British politics, with the old centre ground falling away.

There is intense debate as to what the outcome tells us about voter support for Brexit, with both Leavers and Remainers claiming vindication. The most striking feature of the results, however, is the polarisation they reveal. The result of a botched Brexit has been the Europeanisation of British politics, with the old centre ground falling away. As a literary scholar and authority on African American history, Henry Louis Gates Jr. has written or co-written 24 books and serves on the faculty of Harvard University. But he didn’t achieve broad public attention until he began hosting “Finding Your Roots,” a popular PBS series in which celebrities explore their ancestry, often with surprising results. During an episode of a related program, “African American Lives 2,” comedian Chris Rock discovers that his great-great-grandfather, Julius Caesar Tingman, had fought for the Union with the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War, then served in the South Carolina legislature under its Reconstruction government. The revelation brought the typically glib Rock to tears. “How in the world could I not know this?” Rock asked Gates.

As a literary scholar and authority on African American history, Henry Louis Gates Jr. has written or co-written 24 books and serves on the faculty of Harvard University. But he didn’t achieve broad public attention until he began hosting “Finding Your Roots,” a popular PBS series in which celebrities explore their ancestry, often with surprising results. During an episode of a related program, “African American Lives 2,” comedian Chris Rock discovers that his great-great-grandfather, Julius Caesar Tingman, had fought for the Union with the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War, then served in the South Carolina legislature under its Reconstruction government. The revelation brought the typically glib Rock to tears. “How in the world could I not know this?” Rock asked Gates. In the Netflix anime series Knights of Sidonia, humankind is marooned in a spaceship 500,000-strong, refugees constantly on the run from shapeshifting aliens who destroyed Earth over 1,000 years ago. Both the patriarchy and poverty have been smashed. Advances in genetic engineering have allowed androgynous individuals to proliferate and asexual reproduction to become commonplace. Everybody (except the protagonist, a clone of his grandfather) can photosynthesize, drastically reducing the need to eat. A plot twist near the end of the first season, released in 2014, revealed the existence of a shadow government called the Immortal Ship Committee which, in the last several centuries, had grown in number, from less than 10 members to just under 30, becoming more and more corrupt and self-serving. One of them, a 600-year-old woman named

In the Netflix anime series Knights of Sidonia, humankind is marooned in a spaceship 500,000-strong, refugees constantly on the run from shapeshifting aliens who destroyed Earth over 1,000 years ago. Both the patriarchy and poverty have been smashed. Advances in genetic engineering have allowed androgynous individuals to proliferate and asexual reproduction to become commonplace. Everybody (except the protagonist, a clone of his grandfather) can photosynthesize, drastically reducing the need to eat. A plot twist near the end of the first season, released in 2014, revealed the existence of a shadow government called the Immortal Ship Committee which, in the last several centuries, had grown in number, from less than 10 members to just under 30, becoming more and more corrupt and self-serving. One of them, a 600-year-old woman named  Trying to get a point across in public writing, whether established or clickbait media (a distinction of vanishing significance), with just the nuance, force, and connotations you intend, is like trying to perform a violin solo underwater. You can be as virtuosic as you like, but the medium you’re playing in is going to distort the signal to the point that your effort becomes a vain expenditure, and the result of it comes across as a dull, warped, and muted sound wave to which silence would have been preferable.

Trying to get a point across in public writing, whether established or clickbait media (a distinction of vanishing significance), with just the nuance, force, and connotations you intend, is like trying to perform a violin solo underwater. You can be as virtuosic as you like, but the medium you’re playing in is going to distort the signal to the point that your effort becomes a vain expenditure, and the result of it comes across as a dull, warped, and muted sound wave to which silence would have been preferable. Critics are often maligned.

Critics are often maligned.  What year is it? It’s 2019, obviously. An easy question. Last year was 2018. Next year will be 2020. We are confident that a century ago it was 1919, and in 1,000 years it will be 3019, if there is anyone left to name it. All of us are fluent with these years; we, and most of the world, use them without thinking. They are ubiquitous. As a child I used to line up my pennies by year of minting, and now I carefully note dates of publication in my scholarly articles.

What year is it? It’s 2019, obviously. An easy question. Last year was 2018. Next year will be 2020. We are confident that a century ago it was 1919, and in 1,000 years it will be 3019, if there is anyone left to name it. All of us are fluent with these years; we, and most of the world, use them without thinking. They are ubiquitous. As a child I used to line up my pennies by year of minting, and now I carefully note dates of publication in my scholarly articles. The tech giants are facing a moment of reckoning. Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Uber all grew explosively over the last decade, in part by delivering real convenience and benefits to consumers. For this we forgave their more venial sins, such as unfair competition, copyright infringement, data hoarding, and price discrimination. But recent years have brought one revelation after another around privacy issues—including Facebook’s sharing of data with the dark arts firm Cambridge Analytica—and ever-growing worries about the tech giants’ monopoly powers.

The tech giants are facing a moment of reckoning. Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Uber all grew explosively over the last decade, in part by delivering real convenience and benefits to consumers. For this we forgave their more venial sins, such as unfair competition, copyright infringement, data hoarding, and price discrimination. But recent years have brought one revelation after another around privacy issues—including Facebook’s sharing of data with the dark arts firm Cambridge Analytica—and ever-growing worries about the tech giants’ monopoly powers.