Olúfémi O. Táíwò in The Nation:

Agnes Callard’s Open Socrates is like many works of philosophy: It is addressed to a certain kind of skeptic. Most philosophical works are addressed to skeptics, but they tend to be philosophical skeptics—the metaphysician who doesn’t find arguments for the existence of the external world convincing, the philosopher of knowledge who isn’t quite sure our hunches count as “knowledge,” the moral philosopher who hears talk of “normativity” and can’t shake the mental image of a cop barking orders ultimately backed by violence rather than deep moral truth. Those skeptics are, at bottom, in on it: They are moved and movable by philosophical argument, or so we imagine.

Agnes Callard’s Open Socrates is like many works of philosophy: It is addressed to a certain kind of skeptic. Most philosophical works are addressed to skeptics, but they tend to be philosophical skeptics—the metaphysician who doesn’t find arguments for the existence of the external world convincing, the philosopher of knowledge who isn’t quite sure our hunches count as “knowledge,” the moral philosopher who hears talk of “normativity” and can’t shake the mental image of a cop barking orders ultimately backed by violence rather than deep moral truth. Those skeptics are, at bottom, in on it: They are moved and movable by philosophical argument, or so we imagine.

Callard’s book is addressed to a different kind of skeptic: the one skeptical of the philosophical life. As she writes in the introduction, even academic philosophers often separate the rest of their own lives from their philosophical inquiry and give anodyne and bloodless justifications, such as the development of “critical thinking skills,” when pressed about the discipline’s value. This evasion amounts to the conviction for many of us that we are already intellectual enough about how we live our lives and that we shouldn’t “overdo it” when it comes to living reflectively. Callard wants to make the case for taking a different path, for the examined life: a life of courage and curiosity that is modeled, she argues, after Socrates and his approach to relentless questioning and open-ended philosophical conversations.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

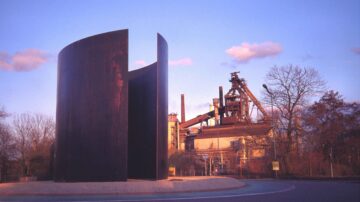

I can imagine collecting, printing out, piling up all the books and journal articles produced on Richard Serra and how closely those stacks might equal the 320 tons (or 11 ½ feet) of Equal, eight boxes of equal volume but different dimensions stacked so that the immediate impression is one of simultaneous solidity and precarity. Over the past half century the art history industry has produced reams of interpretation, incorporating no shortage of words by Serra himself. The author of work so totally laconic has set the terms of its understanding as if the death of the author bypassed him entirely. I think of the spokesartist Robert Motherwell, who expended an awful lot of energy not so much on auto-interpretation as on ennobling a generation of abstract expressionist men, heroic and sublime (Vir Heroicus Sublimus, the painting by Serra influence Barnett Newman, on view two floors up from Equal at MoMA). After shoring up his and his friends’ reputations, Motherwell spent his later career relentlessly churning out canvases to finance his East Hampton house and lifestyle. Less defined by the company he kept than the space he occupied, Serra died at 85, in March 2024, in Orient. Serra had long kept a home and studio, designed by the same architect who transformed so many industrial structures for the display of his sculptures and who built a weekend house next door, on the tip of Long Island’s more rugged but still very expensive North Fork.

I can imagine collecting, printing out, piling up all the books and journal articles produced on Richard Serra and how closely those stacks might equal the 320 tons (or 11 ½ feet) of Equal, eight boxes of equal volume but different dimensions stacked so that the immediate impression is one of simultaneous solidity and precarity. Over the past half century the art history industry has produced reams of interpretation, incorporating no shortage of words by Serra himself. The author of work so totally laconic has set the terms of its understanding as if the death of the author bypassed him entirely. I think of the spokesartist Robert Motherwell, who expended an awful lot of energy not so much on auto-interpretation as on ennobling a generation of abstract expressionist men, heroic and sublime (Vir Heroicus Sublimus, the painting by Serra influence Barnett Newman, on view two floors up from Equal at MoMA). After shoring up his and his friends’ reputations, Motherwell spent his later career relentlessly churning out canvases to finance his East Hampton house and lifestyle. Less defined by the company he kept than the space he occupied, Serra died at 85, in March 2024, in Orient. Serra had long kept a home and studio, designed by the same architect who transformed so many industrial structures for the display of his sculptures and who built a weekend house next door, on the tip of Long Island’s more rugged but still very expensive North Fork. Four billion years ago, our planet was water and barren rock. Out of this, some mighty complicated chemistry bubbled up, perhaps in a pond or a deep ocean vent. Eventually, that chemistry got wrapped in membranes, a primitive cell developed and life emerged from the ooze.

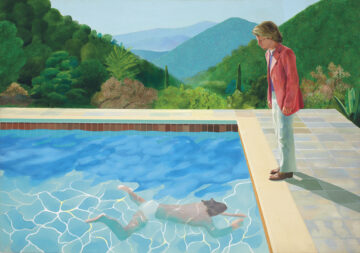

Four billion years ago, our planet was water and barren rock. Out of this, some mighty complicated chemistry bubbled up, perhaps in a pond or a deep ocean vent. Eventually, that chemistry got wrapped in membranes, a primitive cell developed and life emerged from the ooze. If image-making is what drives him still, the possibilities of technology are also an ongoing fascination. He is one of the great draughtsmen of the 20th century but has long been happy to lay aside his pencil to tinker with art made by whatever new toy came into view – Polaroid collages, photocopiers, fax machines, multiple high-res camera rigs, and his iPad (with Apple even devising bespoke software for him). Hockney is a proselytiser, claiming that artists through history have always made use of emerging technologies. While these tools may have helped him scratch his itch, they are to many viewers a distraction and have sidetracked him from his greatest strengths. The artist, who has been heavily involved in putting together the Paris exhibition, has included a selection of these diversions: they clearly remain important to him.

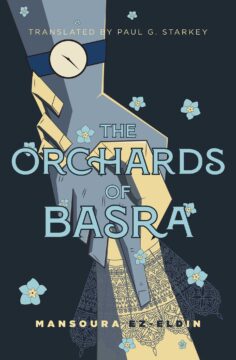

If image-making is what drives him still, the possibilities of technology are also an ongoing fascination. He is one of the great draughtsmen of the 20th century but has long been happy to lay aside his pencil to tinker with art made by whatever new toy came into view – Polaroid collages, photocopiers, fax machines, multiple high-res camera rigs, and his iPad (with Apple even devising bespoke software for him). Hockney is a proselytiser, claiming that artists through history have always made use of emerging technologies. While these tools may have helped him scratch his itch, they are to many viewers a distraction and have sidetracked him from his greatest strengths. The artist, who has been heavily involved in putting together the Paris exhibition, has included a selection of these diversions: they clearly remain important to him. A chronicler of the chimeric, the Egyptian writer Mansoura Ez Eldin has been celebrated in the Arab world for her feverish, fanciful plots. To read her feels like opening one’s eyes into a fugue state, a landscape in which the parameters of reality seem just slightly off-kilter. The air, in her universe, is always abuzz with ethereal presences and diaphanous bodies, anticipating the propitious moment for revelation. For someone so tuned to the monstrous and the ghostly, it’s unsurprising that Ez Eldin’s range of references encompasses everything from Arab-Islamic folklore and A Thousand and One Nights to Franz Kafka and Italo Calvino. Born in the Nile Delta and trained as a journalist, she now works as an editor at the cultural weekly Akhbar al-Adab—a background that has perhaps primed her for the dizzying hall-of-mirror densities of intertextual allusion that characterize her inventive oeuvre.

A chronicler of the chimeric, the Egyptian writer Mansoura Ez Eldin has been celebrated in the Arab world for her feverish, fanciful plots. To read her feels like opening one’s eyes into a fugue state, a landscape in which the parameters of reality seem just slightly off-kilter. The air, in her universe, is always abuzz with ethereal presences and diaphanous bodies, anticipating the propitious moment for revelation. For someone so tuned to the monstrous and the ghostly, it’s unsurprising that Ez Eldin’s range of references encompasses everything from Arab-Islamic folklore and A Thousand and One Nights to Franz Kafka and Italo Calvino. Born in the Nile Delta and trained as a journalist, she now works as an editor at the cultural weekly Akhbar al-Adab—a background that has perhaps primed her for the dizzying hall-of-mirror densities of intertextual allusion that characterize her inventive oeuvre. Language isn’t always necessary. While it certainly helps in getting across certain ideas, some neuroscientists have argued that many forms of human thought and reasoning don’t require the medium of words and grammar. Sometimes, the argument goes, having to turn ideas into language actually slows down the thought process.

Language isn’t always necessary. While it certainly helps in getting across certain ideas, some neuroscientists have argued that many forms of human thought and reasoning don’t require the medium of words and grammar. Sometimes, the argument goes, having to turn ideas into language actually slows down the thought process. Larry Summers: No, I’m feeling like I’m part of some kind of Kafkaesque economic tragedy. I think the master narrative, the big picture here, Yascha, is that the United States is turning itself into an emerging or a submerging market. There are set patterns that we associate with mature democracies. There are set patterns that we associate with developing countries, for which some people would use the term “banana republic.”

Larry Summers: No, I’m feeling like I’m part of some kind of Kafkaesque economic tragedy. I think the master narrative, the big picture here, Yascha, is that the United States is turning itself into an emerging or a submerging market. There are set patterns that we associate with mature democracies. There are set patterns that we associate with developing countries, for which some people would use the term “banana republic.” Pope Francis, who rose from modest means in Argentina to become the first Jesuit and Latin American pontiff, who clashed bitterly with traditionalists in his push for a more inclusive Roman Catholic Church, and who spoke out tirelessly for migrants, the marginalized and the health of the planet, died on Monday at the Vatican’s Casa Santa Marta. He was 88. The pope’s death was announced by the Vatican in

Pope Francis, who rose from modest means in Argentina to become the first Jesuit and Latin American pontiff, who clashed bitterly with traditionalists in his push for a more inclusive Roman Catholic Church, and who spoke out tirelessly for migrants, the marginalized and the health of the planet, died on Monday at the Vatican’s Casa Santa Marta. He was 88. The pope’s death was announced by the Vatican in  The world is a mess.

The world is a mess. Scientists just unveiled the world’s tiniest pacemaker. Smaller than a grain of rice and controlled by light shone through the skin, the pacemaker generates power and squeezes the heart’s muscles after injection through a stint. The device showed it could steadily orchestrate healthy heart rhythms in rat, dog, and human hearts in a

Scientists just unveiled the world’s tiniest pacemaker. Smaller than a grain of rice and controlled by light shone through the skin, the pacemaker generates power and squeezes the heart’s muscles after injection through a stint. The device showed it could steadily orchestrate healthy heart rhythms in rat, dog, and human hearts in a  Yesterday on Warren Street, Richard and I bumped into our friend Jake. If you are recognized on Warren Street, it answers many questions for the rest of the day. I said to Jake, “I love you.” I said, “Richard and I both love you.” Jake owns a shop and sees you in the way Godot would see you if he ever showed up. No one on Warren Street is waiting for Godot. If anything, we are waiting for Godot to leave. Jake said he had bottles of scented oil and he would give me some. It’s one of those offers You have to weigh to yourself, if you are going to remind him. People can be more generous than they bargain for.

Yesterday on Warren Street, Richard and I bumped into our friend Jake. If you are recognized on Warren Street, it answers many questions for the rest of the day. I said to Jake, “I love you.” I said, “Richard and I both love you.” Jake owns a shop and sees you in the way Godot would see you if he ever showed up. No one on Warren Street is waiting for Godot. If anything, we are waiting for Godot to leave. Jake said he had bottles of scented oil and he would give me some. It’s one of those offers You have to weigh to yourself, if you are going to remind him. People can be more generous than they bargain for.