Benjamin Kunkel in Harper’s Magazine:

Let us approach Capital as naïvely as possible, while admitting that in the case of Capital this decision can hardly be anything but a ruse. The ruseful naïveté I have in mind will consist in our pretending not to have any extratextual information about the book—in particular, information about the enormous literature of partisan commentary that has grown up around Marx’s analysis of capitalism or about the international Communist movement that took Capital for its warrant.

Let us approach Capital as naïvely as possible, while admitting that in the case of Capital this decision can hardly be anything but a ruse. The ruseful naïveté I have in mind will consist in our pretending not to have any extratextual information about the book—in particular, information about the enormous literature of partisan commentary that has grown up around Marx’s analysis of capitalism or about the international Communist movement that took Capital for its warrant.

The paragraph above copies almost word for word the first sentences of “Against Ulysses,” a 1988 essay by the critic Leo Bersani about another book whose reputation almost ruinously precedes it, namely Joyce’s novel about a June day in Dublin. Such helpless plagiarism on my part (turns out I couldn’t imagine a naïve or innocent reading of Capital without recalling Bersani’s similar gambit) should by itself imply how hard it is to achieve true naïveté in the face of an exceptionally famous book. Already it was more than 140 years ago that an old man named Karl Marx and an infant baptized James Augustine Joyce shared the air for some thirteen months, and by now all the endless discussion of the notorious books that these writers produced means that any attempt to read them in a spirit of innocence smacks of too much experience. I was just a kid when I first heard of Das Kapital, evidently such a sinister title that, like Mein Kampf, it could only be uttered in German. Most people have been hearing about Marx and Marxism forever; even Donald Trump, whom no one would suspect of having read Capital, routinely castigates his opponents as Marxists.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Parenting teenagers

Parenting teenagers In the Preface to his landmark Dictionary of 1755, Samuel Johnson wrote that ‘sounds are too volatile and subtile for legal restraints; to enchain syllables, and to lash the wind, are equally the undertakings of pride’. Any dictionary, any grammar, is but a snapshot: all living languages change, and they do so constantly and at every level.

In the Preface to his landmark Dictionary of 1755, Samuel Johnson wrote that ‘sounds are too volatile and subtile for legal restraints; to enchain syllables, and to lash the wind, are equally the undertakings of pride’. Any dictionary, any grammar, is but a snapshot: all living languages change, and they do so constantly and at every level. Like many proud parents,

Like many proud parents,  “America, América” is implicitly a companion volume to Grandin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning

“America, América” is implicitly a companion volume to Grandin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning  We hoped that our collective struggles had made a difference in ending a war that never should have been fought.

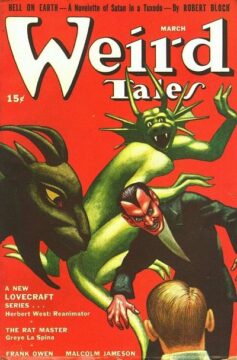

We hoped that our collective struggles had made a difference in ending a war that never should have been fought. A proposition: though “trash art” remains with us, the trash artist is a dying species. Trash art is focus-grouped these days, high-gloss. Trash art is a direct-to-streaming show full of people who are slightly too attractive that’s meant to be played in the background while you play Candy Crush on your phone. Even our truly lowbrow cultural productions, like The Bachelor, are not the product of particular people; they’re crafted through a system. Without romanticizing the old days of pulp magazines and Brill Building song writers, we can—ah hell! Let’s romanticize them. Why not? They certainly put out lots of garbage, but it was honest human garbage. Look at an old issue of Weird Tales—in terms of nostalgic reverence, the Partisan Review of pulp fiction—with its now charmingly dated pinup girls on the cover, and its promise of many stupid adventures within, and try not to romanticize it.

A proposition: though “trash art” remains with us, the trash artist is a dying species. Trash art is focus-grouped these days, high-gloss. Trash art is a direct-to-streaming show full of people who are slightly too attractive that’s meant to be played in the background while you play Candy Crush on your phone. Even our truly lowbrow cultural productions, like The Bachelor, are not the product of particular people; they’re crafted through a system. Without romanticizing the old days of pulp magazines and Brill Building song writers, we can—ah hell! Let’s romanticize them. Why not? They certainly put out lots of garbage, but it was honest human garbage. Look at an old issue of Weird Tales—in terms of nostalgic reverence, the Partisan Review of pulp fiction—with its now charmingly dated pinup girls on the cover, and its promise of many stupid adventures within, and try not to romanticize it. The Trump administration

The Trump administration  Last Wednesday night I received an email out of the blue from Larry David, the comedian and creator of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” saying that he had a guest essay submission. I opened the document and read the first line: “Imagine my surprise when in the spring of 1939 a letter arrived at my house inviting me to dinner at the Old Chancellery with the world’s most reviled man, Adolf Hitler.”

Last Wednesday night I received an email out of the blue from Larry David, the comedian and creator of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” saying that he had a guest essay submission. I opened the document and read the first line: “Imagine my surprise when in the spring of 1939 a letter arrived at my house inviting me to dinner at the Old Chancellery with the world’s most reviled man, Adolf Hitler.” I don’t carry a camera in my hometown of Chapel Hill, and even though my cellphone contains a camera, I use it only for snapshots. Naturally, there were moments when I wished I had a camera with me. Once, while walking in my neighborhood at twilight, I felt a strange rush of energy in the air, and, suddenly, no more than twenty feet away, a majestically antlered whitetail buck soared over a garden fence and hurtled down the dimming street. Yet even as it was happening—this unexpectedly preternatural moment—I tried to imagine it as a photograph. That’s how we’ve been taught to think. “Oh, I wish I’d had a camera!” But that presumes I would have been prepared to capture the moment—instead of being startled by it. Yet being startled by beauty is a uniquely, and all too rare, human gift. The photograph comes later, when I journey back from astonishment and begin to fiddle with my camera.

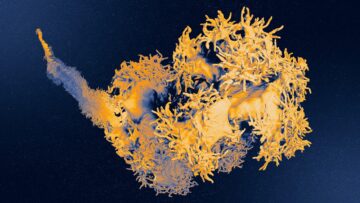

I don’t carry a camera in my hometown of Chapel Hill, and even though my cellphone contains a camera, I use it only for snapshots. Naturally, there were moments when I wished I had a camera with me. Once, while walking in my neighborhood at twilight, I felt a strange rush of energy in the air, and, suddenly, no more than twenty feet away, a majestically antlered whitetail buck soared over a garden fence and hurtled down the dimming street. Yet even as it was happening—this unexpectedly preternatural moment—I tried to imagine it as a photograph. That’s how we’ve been taught to think. “Oh, I wish I’d had a camera!” But that presumes I would have been prepared to capture the moment—instead of being startled by it. Yet being startled by beauty is a uniquely, and all too rare, human gift. The photograph comes later, when I journey back from astonishment and begin to fiddle with my camera. For decades, neuroscientists have thought that the brain learns by changing how neurons are connected to one another. As new information and experiences alter how neurons communicate with each other and change their collective activity patterns, some synaptic connections are made stronger while others are made weaker. This process of

For decades, neuroscientists have thought that the brain learns by changing how neurons are connected to one another. As new information and experiences alter how neurons communicate with each other and change their collective activity patterns, some synaptic connections are made stronger while others are made weaker. This process of  It’s been nearly two decades since I finished my undergraduate degree, and my memories of my philosophy major, like most things associated with one’s early adulthood, are hazy at best.

It’s been nearly two decades since I finished my undergraduate degree, and my memories of my philosophy major, like most things associated with one’s early adulthood, are hazy at best.