Category: Recommended Reading

The Argument Against Quantum Computers

Katia Moskvitch in Quanta:

Katia Moskvitch in Quanta:

Sixteen years ago, on a cold February day at Yale University, a poster caught Gil Kalai’s eye. It advertised a series of lectures by Michel Devoret, a well-known expert on experimental efforts in quantum computing. The talks promised to explore the question “Quantum Computer: Miracle or Mirage?” Kalai expected a vigorous discussion of the pros and cons of quantum computing. Instead, he recalled, “the skeptical direction was a little bit neglected.” He set out to explore that skeptical view himself.

Today, Kalai, a mathematician at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, is one of the most prominent of a loose group of mathematicians, physicists and computer scientists arguing that quantum computing, for all its theoretical promise, is something of a mirage. Some argue that there exist good theoretical reasons why the innards of a quantum computer — the “qubits” — will never be able to consistently perform the complex choreography asked of them. Others say that the machines will never work in practice, or that if they are built, their advantages won’t be great enough to make up for the expense.

Kalai has approached the issue from the perspective of a mathematician and computer scientist. He has analyzed the issue by looking at computational complexity and, critically, the issue of noise. All physical systems are noisy, he argues, and qubits kept in highly sensitive “superpositions” will inevitably be corrupted by any interaction with the outside world. Getting the noise down isn’t just a matter of engineering, he says. Doing so would violate certain fundamental theorems of computation.

More here.

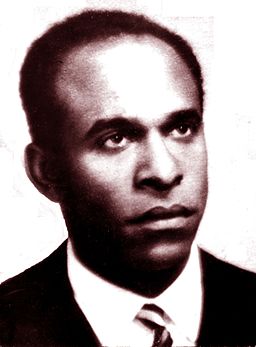

Frantz Fanon and the CIA Man

Thomas Meaney in The American Historical Review:

Thomas Meaney in The American Historical Review:

THE IMAGE IS NOT lacking in irony: Frantz Fanon, the intellectual father of Third World revolution, lying in a Maryland hospital bed, watched over by a blue-blooded agent of the CIA. It was out of desperation and his lack of success with Soviet doctors, Fanon’s biographer David Macey reports, that Fanon had agreed to American offers to fly him to the United States—“that country of lynchers,” as he called it—for leukemia treatment. The benefit of aiding the figure who wrote of “a murderous and decisive confrontation” between the colonial and the colonized world was not lost on the CIA. The gesture could have been intended to shore up the United States’ anticolonial credentials in the Cold War, and/or to signal the feebleness of radical national liberation movements whose leaders were compromised by relations with U.S. intelligence. Eight years after Fanon’s death in 1961, Joe Alsop made the latter argument when he leaked the story of the circumstances of Fanon’s last hours in his column in the Washington Post. Writing at a low point in America’s war in Vietnam, Alsop, a leading rhapsodist of pro-war opinion, wanted to score a point at the Third World’s expense. “The chief black hero of the New Left,” he gloated, had died “almost literally in the arms of the CIA.” Alsop savored the CIA case officer’s “downright brotherly visits” to Fanon’s bedside. “Altogether,” he wrote, “it is like saying that Che Guevara died, not because of, but despite the best efforts of the Central Intelligence Agency.” Alsop sent his column to Hannah Arendt, a severe critic of Fanon’s thought and style of expression, whose essay “On Violence” Alsop claimed had “inspired” him. “It almost could move one to tender feelings toward the CIA,” Arendt responded. “Seriously, it shows a certain humanity that is consoling.”

More here.

Pop-Up Populism: The Failure of Left-Wing Nationalism in Germany

Quinn Slobodian and William Callison in Dissent:

Quinn Slobodian and William Callison in Dissent:

In 2016, a dramaturge, a career politician, and a retired sociologist met at the Paris-Moskau Restaurant in Berlin to hatch a plan to disrupt the German left. The dramaturge was the fifty-something Bernd Stegemann, a large man in wire-framed glasses with the slumped mien of an eternal graduate student. He worked a five-minute cab ride away at the Berliner Ensemble, a theater company founded by Bertolt Brecht in the same year as socialist East Germany.

The politician was Sahra Wagenknecht, one of the country’s most poised and merciless critics of the status quo. Born in East Germany to an Iranian father and a German mother, Wagenknecht was the parliamentary chairperson of die Linke (the Left) party. Since its 2007 founding, die Linke’s mixture of ex–Social Democrats and former East German communists had polled around 10 percent nationally. Despite her party’s mediocre electoral performance, Wagenknecht had remained one of the most popular politicians in national polls and a fixture on primetime talk shows.

More here.

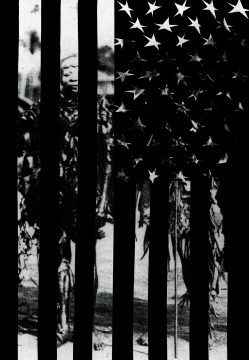

America Wasn’t a Democracy, Until Black Americans Made It One

Nikole Hannah-Jones in the NYT:

Nikole Hannah-Jones in the NYT:

[I]t would be historically inaccurate to reduce the contributions of black people to the vast material wealth created by our bondage. Black Americans have also been, and continue to be, foundational to the idea of American freedom. More than any other group in this country’s history, we have served, generation after generation, in an overlooked but vital role: It is we who have been the perfecters of this democracy.

The United States is a nation founded on both an ideal and a lie. Our Declaration of Independence, approved on July 4, 1776, proclaims that “all men are created equal” and “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.” But the white men who drafted those words did not believe them to be true for the hundreds of thousands of black people in their midst. “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” did not apply to fully one-fifth of the country. Yet despite being violently denied the freedom and justice promised to all, black Americans believed fervently in the American creed. Through centuries of black resistance and protest, we have helped the country live up to its founding ideals.

More here.

Uncle Sam was Born Lethal

Paul Street in Counterpunch:

For revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.

– Frederick Douglass, July 4, 1852

One of the occupational and intellectual hazards of being a historian is that current events often seem far less new to oneself than they do to others. Recently a leftish liberal friend told me that the United States under the Donald Trump had “become a lethal society.” My friend cited the neofascist Trump’s: horrible family separations and concentration camps on the border; openly white-nationalist assaults on four progressive nonwhite and female Congresswomen; real and threatened roundups of undocumented immigrants; fascist-style and hate-filled “Make America Great Again” rallies; encouragement of white supremacist terrorism; alliance with right-wing evangelical Christian fascists.

One of the occupational and intellectual hazards of being a historian is that current events often seem far less new to oneself than they do to others. Recently a leftish liberal friend told me that the United States under the Donald Trump had “become a lethal society.” My friend cited the neofascist Trump’s: horrible family separations and concentration camps on the border; openly white-nationalist assaults on four progressive nonwhite and female Congresswomen; real and threatened roundups of undocumented immigrants; fascist-style and hate-filled “Make America Great Again” rallies; encouragement of white supremacist terrorism; alliance with right-wing evangelical Christian fascists.

Another friend received news of the recent mass-shooting of mostly Latinx Wal-Mart shoppers by racist and nativist white male Trump fan in El Paso, Texas by denouncing Trump’s “fascism” and linking to an essay he’d published about the white-nationalist president’s racist and authoritarian behavior.

I agree with my friends about the lethality of the contemporary United States. I largely share their description of Trump and much of his base as fascist or at least fascistic. “Durable fascist tendencies,” the prolific left political scientist Carl Boggs warns in his important book Fascism Old New: American Politics at the Crossroads, “run deep throughout present-day American society…In the absence of powerful counterforces and a thriving democracy, …those tendencies could morph over into something more expansive and menacing – and Donald Trump could serve, wittingly or unwittingly, as a great historical accelerator.”

It’s nothing to sneeze at. The institutional forms and technologies of militarized surveillance and policing and thought control that are available to fascism-prone elites in the United States are daunting indeed. The United States enjoys historically unprecedented global power on a scale the fascist Third Reich’s leaders dreamed of achieving but never remotely approached.

More here.

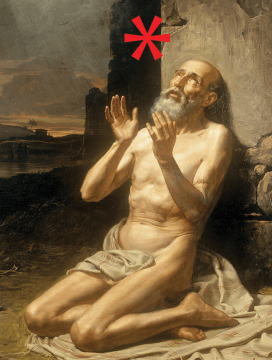

And Then Job Said Unto the Lord: You Can’t Be Serious

James Parker in The Atlantic:

So god says to Satan, “You there, what have you been up to?” And Satan says, “Oh, you know, just hanging around, minding my own business.” And God says, “Well, take a look at my man Job over there. He worships me. He does exactly what I tell him. He thinks I’m the greatest.” “Job?” says Satan. “The rich, happy, healthy guy? The guy with 3,000 camels? Of course he does. You’ve given him everything. Take it all away from him, and I bet you he’ll curse you to your face.” And God says, “You’re on.”

So god says to Satan, “You there, what have you been up to?” And Satan says, “Oh, you know, just hanging around, minding my own business.” And God says, “Well, take a look at my man Job over there. He worships me. He does exactly what I tell him. He thinks I’m the greatest.” “Job?” says Satan. “The rich, happy, healthy guy? The guy with 3,000 camels? Of course he does. You’ve given him everything. Take it all away from him, and I bet you he’ll curse you to your face.” And God says, “You’re on.”

That—give or take a couple of verses—is how it starts, the Book of Job. What a setup. The Trumplike deity; the shrewd and loitering adversary; the cruelly flippant wager; and the stooge, the cosmic straight man, Job, upon whose oblivious head the sky is about to fall. A classic Old Testament skit, pungent as a piece of absurdist theater or a story by Kafka. Job is going to be immiserated, sealed into sorrow—for a bet. What is life? It’s a bleeping and blooping Manichaean casino: You’re up or you’re down, in God’s hands or the devil’s. Piped-in oxygen, controlled light, keep the drinks coming. We, the readers and inheritors of his book, know this. Job, poor bastard, doesn’t.

After his herds have been finished off by marauders and gushes of heavenly fire, and his children have been flattened by falling masonry, and he himself has been covered in running sores from head to toe—after all this happens to the blameless man, he cracks. He sits on an ash heap, seeping and scratching, and reviles the day he was born. “Let that day be darkness,” as the King James Version has it. “Let not God regard it from above, neither let the light shine upon it. Let darkness and the shadow of death stain it; let a cloud dwell upon it; let the blackness of the day terrify it.” Howls of despair are a biblical staple, but Job’s self-curse—the special physics of it, the suicidal pulse that he sends backwards, like a black rainbow, toward the hour of his own conception—is singular. Dispossessed of everything, he is choosing nothing. That first prickle of my existence, the point of light with my name on it? Turn around, All-Fathering One, and eclipse it. Delete.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Leave This

Leave this chanting and singing and telling of beads!

Whom dost thou worship in this lonely dark corner of a temple with doors all shut?

Open thine eyes and see thy God is not before thee!

He is there where the tiller is tilling the hard ground

and where the pathmaker is breaking stones.

He is with them in sun and in shower,

and his garment is covered with dust.

Put off thy holy mantle and even like him come down on the dusty soil!

Friday, August 16, 2019

On Language and Humanity: In Conversation With Noam Chomsky

Amy Brand at The MIT Press Reader:

Amy Brand: You have tended to separate your work on language from your political persona and writings. But is there a tension between arguing for the uniqueness of Homo sapiens when it comes to language, on the one hand, and decrying the human role in climate change and environmental degradation, on the other? That is, might our distance from other species be tied up in how we’ve engaged (or failed to engage) with the natural environment?

Noam Chomsky: The technical work itself is in principle quite separate from personal engagements in other areas. There are no logical connections, though there are some more subtle and historical ones that I’ve occasionally discussed (as have others) and that might be of some significance.

Noam Chomsky: The technical work itself is in principle quite separate from personal engagements in other areas. There are no logical connections, though there are some more subtle and historical ones that I’ve occasionally discussed (as have others) and that might be of some significance.

Homo sapiens is radically different from other species in numerous ways, too obvious to review. Possession of language is one crucial element, with many consequences. With some justice, it has often in the past been considered to be the core defining feature of modern humans, the source of human creativity, cultural enrichment, and complex social structure.

As for the “tension” you refer to, I don’t quite see it.

More here.

Debunking debunked

Emily Ogden in Aeon:

‘Bunk’ means baloney, hooey, bullshit. Bunk isn’t just a lie, it’s a manipulative lie, the sort of thing a con man might try to get you to believe in order to gain control of your mind and your bank account. Bunk, then, is the tool of social parasites, and the word ‘debunk’ carries with it the expectation of clearing out something that is foreign to the healthy organism. Just as you can deworm a puppy, you can debunk a religious practice, a pyramid scheme, a quack cure. Get rid of the nonsense, and the polity – just like the puppy – will fare better. Con men will be deprived of their innocent marks, and the world will take one more step in the direction of modernity.

‘Bunk’ means baloney, hooey, bullshit. Bunk isn’t just a lie, it’s a manipulative lie, the sort of thing a con man might try to get you to believe in order to gain control of your mind and your bank account. Bunk, then, is the tool of social parasites, and the word ‘debunk’ carries with it the expectation of clearing out something that is foreign to the healthy organism. Just as you can deworm a puppy, you can debunk a religious practice, a pyramid scheme, a quack cure. Get rid of the nonsense, and the polity – just like the puppy – will fare better. Con men will be deprived of their innocent marks, and the world will take one more step in the direction of modernity.

Debunk is a story of modernity in one word – but is it a true story? Here’s the way this fable goes. Modernity is when we finally muster the reason and the will to get rid of all the self-interested deceptions that aristocrats and priests had fobbed off on us in the past. Now, the true, healthy condition of human society manifests itself naturally, a state of affairs characterised by democracy, secular values, human rights, a capitalist economy and empowerment for everyone (eventually; soon). All human beings and all human societies are or ought to be headed toward this enviable situation. Some – and these are often non-Western people, people of faiths other than Christianity, people of colour – have regrettably gotten themselves faced in the wrong direction. They are still ‘barbaric’ or ‘medieval’ or even ‘primitive’. Maybe they are even getting more so. Turns out the debunking will have to continue. We’ll have to keep de-worming on an individual, an institutional, or a geopolitical scale until everyone is all right.

But scholars have been pointing out for some time just how far off this picture is.

More here.

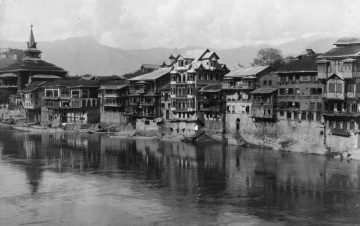

Kashmir: a tale of two mothers

Swaran Singh in Spiked:

Iftikhar was my favourite taxi driver while I lived in London. An elderly Muslim from Lahore, he spoke in lilting, lyrical Punjabi typical of that part of the world. In June 1999, as India and Pakistan fought the Kargil war, he was driving me to Heathrow when the conversation turned to the conflict. I asked what he thought. ‘Doctor sahib‘, he said, ‘when my mother had me, she was suffering from tuberculosis. She was weak and her milk had dried up. Her nextdoor neighbour was a Sikh woman who had also given birth. My mother asked her to breastfeed me. When you ask me about the war, what can I say? I was born of one mother’s womb; another mother suckled me. How can I choose?’

Iftikhar was my favourite taxi driver while I lived in London. An elderly Muslim from Lahore, he spoke in lilting, lyrical Punjabi typical of that part of the world. In June 1999, as India and Pakistan fought the Kargil war, he was driving me to Heathrow when the conversation turned to the conflict. I asked what he thought. ‘Doctor sahib‘, he said, ‘when my mother had me, she was suffering from tuberculosis. She was weak and her milk had dried up. Her nextdoor neighbour was a Sikh woman who had also given birth. My mother asked her to breastfeed me. When you ask me about the war, what can I say? I was born of one mother’s womb; another mother suckled me. How can I choose?’

I thought of Iftikhar as India and Pakistan are again on the brink. On 5 August 2019, Amit Shah, India’s home affairs minister, announcedin the upper house of the Indian parliament (Rajya Sabha) that a presidential order had been issued revoking Article 370, depriving the state of Jammu and Kashmir of its special status that conferred on it a certain level of autonomy, and fundamentally changing the relationship between India and Kashmir.

The immediate and long-term consequences of this Indian move will be far-reaching, and may be very damaging. No one can foresee the outcome and many will rightly be trepidatious. But at this critical juncture, it is important to realise the complexity of the Indian-Pakistani conflict over Kashmir, and its varied victims. Much of the media portrayal of the conflict is one between a Hindu nationalist India and the Muslim population of Kashmir. This is only partly true.

More here.

How the Talking Heads wrote “Once in a Lifetime”

On the Love Hotels and Pleasure Quarters of Tokyo

Anna Sherman at Literary Hub:

Tokyo is a city of darkness, a city of light. Each melts into the other. At its center, the city of light blacks out, and at bridges and crossroads, at the margins around train stations, the city of darkness shines, gleaming.

Tokyo is a city of darkness, a city of light. Each melts into the other. At its center, the city of light blacks out, and at bridges and crossroads, at the margins around train stations, the city of darkness shines, gleaming.

In that other city are love-hotel rooms laid out like train carriages where men brush against women pretending to be commuters. And the (now almost extinct) No Panty coffee houses, which appeared overnight and disappeared as quickly, once Tokyo tired of their mirrored floors and the waitresses who served terrible overpriced coffee, wearing short skirts and nothing else. Before the New Public Morals Act outlawed certain excesses of bad taste (such as revolving beds and oversized mirrors), there were cabarets near Shinjuku where women stood behind chicken wire as clients poked fingers through the mesh, straining to touch a rib, a wrist, or whatever they could reach. Rooms where adults could suck on a pacifier and wear diapers. And—most infamous—Lucky Hole, a bar where a man could push himself through an anonymous plywood board while someone invisible on the other side sucked or stroked him.

more here.

Reading The Hebrew Prophets Today

Rick Baum at The Point:

But how can we think of YHWH as indicating a path away from injustice and oppression? One way we might try to understand Amos’s sense of YHWH in the central passages of the chiasmus is with reference to the notion of wonder. Abraham Joshua Heschel, a prominent twentieth-century theologian, rooted his theology in the teaching of the prophets and particularly in his observation that “to the prophets wonder is a form of thinking … it is an attitude that never ceases.” Importantly, for Heschel, wonder is a real-world experience—one that is latent in every person—resulting from even the most mundane aspects of life. “We do not come upon it only at the climax of thinking or in observing strange, extraordinary facts but in the startling fact that there are facts at all: being, the universe, the unfolding of time,” he writes in God in Search of Man. “We may face it at every turn, in a grain of sand, in an atom, as well as in the stellar space.”

But how can we think of YHWH as indicating a path away from injustice and oppression? One way we might try to understand Amos’s sense of YHWH in the central passages of the chiasmus is with reference to the notion of wonder. Abraham Joshua Heschel, a prominent twentieth-century theologian, rooted his theology in the teaching of the prophets and particularly in his observation that “to the prophets wonder is a form of thinking … it is an attitude that never ceases.” Importantly, for Heschel, wonder is a real-world experience—one that is latent in every person—resulting from even the most mundane aspects of life. “We do not come upon it only at the climax of thinking or in observing strange, extraordinary facts but in the startling fact that there are facts at all: being, the universe, the unfolding of time,” he writes in God in Search of Man. “We may face it at every turn, in a grain of sand, in an atom, as well as in the stellar space.”

more here.

Lee Krasner at The Barbican

T.J. Clark at the LRB:

The Prophecy pictures were made in tragic circumstances. By 1956 Krasner’s marriage to Jackson Pollock was all but broken. In August that year, while Krasner was in Europe, Pollock’s Oldsmobile came off the road at speed, killing himself and Edith Metzger, a friend of his lover, Ruth Kligman. Kligman survived the crash. The paintings Krasner made in response to the horror – and this is almost always her strength – are deeply engaged with other people’s imagery. Fighting with De Kooning’s Woman, as she does throughout – fighting and feeding on his colour, the scale and shape of his Cubist body parts, his bad faith fascination with Marilyn Monroe gorgeousness (bad faith because his irony is so obviously an alibi for gloating) – is her way of discovering what ‘woman’, that terrifying abstraction, meant for her. Out of the engagement comes the originality. Dripping paint, for example, was already a tired Ab Ex trademark by 1956, by no means De Kooning’s exclusive property. But no one had made dripped paint so unlovely, so impatient and passionless, as Krasner did the pinks and whites in Birth. (The tone of the title is undecidable.) For the fight with De Kooning to end in victory, other painters’ weaponry had to be taken out of the closet, some of it distinctly old-fashioned. Krasner was never up to date. Three in Two, for example, evokes explicitly, and not just in its title, the savage Jungian splitting and swapping of genders that Pollock had gone in for a decade earlier, during the time of Two and Male and Female. Behind those paintings lay Picasso, specifically Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Krasner was monstrously confident that she could mobilise this big machinery without in the least repeating its moves – or rather, that she could use the moves to deliver an entirely new, and dreadful, sense of closeness and inhumanity. Embrace, for example, is Les Demoiselles churned into viscera.

The Prophecy pictures were made in tragic circumstances. By 1956 Krasner’s marriage to Jackson Pollock was all but broken. In August that year, while Krasner was in Europe, Pollock’s Oldsmobile came off the road at speed, killing himself and Edith Metzger, a friend of his lover, Ruth Kligman. Kligman survived the crash. The paintings Krasner made in response to the horror – and this is almost always her strength – are deeply engaged with other people’s imagery. Fighting with De Kooning’s Woman, as she does throughout – fighting and feeding on his colour, the scale and shape of his Cubist body parts, his bad faith fascination with Marilyn Monroe gorgeousness (bad faith because his irony is so obviously an alibi for gloating) – is her way of discovering what ‘woman’, that terrifying abstraction, meant for her. Out of the engagement comes the originality. Dripping paint, for example, was already a tired Ab Ex trademark by 1956, by no means De Kooning’s exclusive property. But no one had made dripped paint so unlovely, so impatient and passionless, as Krasner did the pinks and whites in Birth. (The tone of the title is undecidable.) For the fight with De Kooning to end in victory, other painters’ weaponry had to be taken out of the closet, some of it distinctly old-fashioned. Krasner was never up to date. Three in Two, for example, evokes explicitly, and not just in its title, the savage Jungian splitting and swapping of genders that Pollock had gone in for a decade earlier, during the time of Two and Male and Female. Behind those paintings lay Picasso, specifically Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Krasner was monstrously confident that she could mobilise this big machinery without in the least repeating its moves – or rather, that she could use the moves to deliver an entirely new, and dreadful, sense of closeness and inhumanity. Embrace, for example, is Les Demoiselles churned into viscera.

more here.

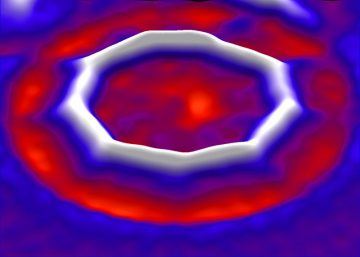

Chemists make first-ever ring of pure carbon

Long after most chemists had given up trying, a team of researchers has synthesized the first ring-shaped molecule of pure carbon — a circle of 18 atoms. The chemists started with a triangular molecule of carbon and oxygen, which they manipulated with electric currents to create the carbon-18 ring. Initial studies of the properties of the molecule, called a cyclocarbon, suggest that it acts as a semiconductor, which could make similar straight carbon chains useful as molecular-scale electronic components. It is an “absolutely stunning work” that opens up a new field of investigation, says Yoshito Tobe, a chemist at Osaka University in Japan. “Many scientists, including myself, have tried to capture cyclocarbons and determine their molecular structures, but in vain,” Tobe says. The results appear in Science1 on 15 August.

Long after most chemists had given up trying, a team of researchers has synthesized the first ring-shaped molecule of pure carbon — a circle of 18 atoms. The chemists started with a triangular molecule of carbon and oxygen, which they manipulated with electric currents to create the carbon-18 ring. Initial studies of the properties of the molecule, called a cyclocarbon, suggest that it acts as a semiconductor, which could make similar straight carbon chains useful as molecular-scale electronic components. It is an “absolutely stunning work” that opens up a new field of investigation, says Yoshito Tobe, a chemist at Osaka University in Japan. “Many scientists, including myself, have tried to capture cyclocarbons and determine their molecular structures, but in vain,” Tobe says. The results appear in Science1 on 15 August.

Pure carbon comes in several different forms, including diamond, graphite and ‘nanotubes’. Atoms of the element can form chemical bonds with themselves in various configurations: for example, each atom can bind to four neighbours in a pyramid-shaped pattern, as in diamond; or to three, as in the hexagonal patterns that make up the single-atom-thick sheets of graphene. (Such a three-bond pattern is also found in bulk graphite as well as in carbon nanotubes and in the globular molecules called fullerenes.) But carbon can also form bonds with just two nearby atoms. Nobel-prizewinning chemist Roald Hoffmann at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and others have long theorized that this would lead to pure chains of carbon atoms. Each atom might form either a double bond on each side — meaning the adjacent atoms share two electrons — or a triple bond on one side and a single bond on the other. Various teams have attempted to synthesize rings or chains based on this pattern.

More here.

Friday Poem

Crows over the Wheatfield

After Van Gogh

I have done with the sun.

Here on these northern

plains wheat fields become

waves, beneath leaden skies,

shadows black of dogs

run through the swaying crop.

Long ago I left another country

where the sulphurous sun

hung low over the potato fields.

They called me a madman

because I wanted to be a

true Christian. In Arles

I painted blossom pure as

drifts of Japanese snow.

Now it is upon me again,

this clamped crown.

I who melted gold into

an alchemy of sunflowers

burnished as a lion’s mane.

Misfortune must be good

for something…

Across the wheat field crows

wheel in a ragged requiem

towards me. My vision

shifts and slides. Three paths

diverge – leading somewhere

going nowhere. My eyes

burn. I cannot hold on.

by Sue Hubbard

from Ghost Station

saltpublishing 2004

Painting:

Vincent Van Gogh

Wheatfield with Crows

Thursday, August 15, 2019

What Ails the Right Isn’t (Just) Racism

Conor Friedersdorf in The Atlantic:

I concur that Trump, as surely as Lee Atwater, marshals racist tropes. But I doubt the last claim: “Instrumental racists” believe that voters will perhaps respond only to racism. And I doubt that voters, in fact, respond only to racism. Something distinct and deeper is at work. This deeper force explains nearly all of Trump’s most odious and irresponsible comments, not just the racist ones. It helps explain why so many conservatives and Republicans were caught off guard by Trump’s rise and the resonance of his bigotry. And it helps clarify what the left sees and doesn’t see about racism. Once leftists understand it, they will find it easier to defeat the identitarian right.

I concur that Trump, as surely as Lee Atwater, marshals racist tropes. But I doubt the last claim: “Instrumental racists” believe that voters will perhaps respond only to racism. And I doubt that voters, in fact, respond only to racism. Something distinct and deeper is at work. This deeper force explains nearly all of Trump’s most odious and irresponsible comments, not just the racist ones. It helps explain why so many conservatives and Republicans were caught off guard by Trump’s rise and the resonance of his bigotry. And it helps clarify what the left sees and doesn’t see about racism. Once leftists understand it, they will find it easier to defeat the identitarian right.

No one better anticipated today’s societal divisions than the political psychologist Karen Stenner, author of the 2005 book The Authoritarian Dynamic. The book built on research literature that distinguishes between “authoritarians,” who prize what Stenner calls “oneness and sameness” so much so that they are prone to support coercion to effect it, and “libertarians,” who not only defend but affirmatively prize diversity and difference. (Those labels are not to be conflated with the popular definitions of the terms.)

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Adam Becker on the Curious History of Quantum Mechanics

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

There are many mysteries surrounding quantum mechanics. To me, the biggest mysteries are why physicists haven’t yet agreed on a complete understanding of the theory, and even more why they mostly seem content not to try. This puzzling attitude has historical roots that go back to the Bohr-Einstein debates. Adam Becker, in his book What Is Real?, looks at this history, and discusses how physicists have shied away from the foundations of quantum mechanics in the subsequent years. We discuss why this has been the case, and talk about some of the stubborn iconoclasts who insisted on thinking about it anyway.

There are many mysteries surrounding quantum mechanics. To me, the biggest mysteries are why physicists haven’t yet agreed on a complete understanding of the theory, and even more why they mostly seem content not to try. This puzzling attitude has historical roots that go back to the Bohr-Einstein debates. Adam Becker, in his book What Is Real?, looks at this history, and discusses how physicists have shied away from the foundations of quantum mechanics in the subsequent years. We discuss why this has been the case, and talk about some of the stubborn iconoclasts who insisted on thinking about it anyway.

More here.

Against Literalism—’The Satanic Verses’ Fatwa at 30

Daniel James Sharp in Quillette:

The novel’s protagonists are Indian-born Muslims. Saladin is a voiceover artist and an immigrant from Bombay to London whose shame about his Indian-ness and desire to be anglicised form the backdrop to a complex interrogation of what it means to be rootless and how migrants in a globalised world can find a sense of identity. Gibreel, meanwhile, is a legend of the Bombay movie scene whose recent health crisis has led him to lose his faith and travel to London to be with the woman he loves, Alleluia Cone. Famous for portraying Hindu gods on screen, Gibreel’s newfound archangelic nature sorely tests his mind—a newly godless man condemned to act as God’s (or is that Satan’s?) right hand on earth.

The novel’s protagonists are Indian-born Muslims. Saladin is a voiceover artist and an immigrant from Bombay to London whose shame about his Indian-ness and desire to be anglicised form the backdrop to a complex interrogation of what it means to be rootless and how migrants in a globalised world can find a sense of identity. Gibreel, meanwhile, is a legend of the Bombay movie scene whose recent health crisis has led him to lose his faith and travel to London to be with the woman he loves, Alleluia Cone. Famous for portraying Hindu gods on screen, Gibreel’s newfound archangelic nature sorely tests his mind—a newly godless man condemned to act as God’s (or is that Satan’s?) right hand on earth.

But both protagonists are hybrids who contain elements of the saintly and the diabolical. They both face challenges and crises of identity. Through them, Rushdie explores what it means to lose and then find one’s identity and what the true experience is of migrants whose rootlessness and existence in a foreign culture leads to a crisis of selfhood. The intermingling of elements—culture, language, religion—is celebrated, while the concept of purity in identity and culture is repudiated as too constricting.

More here.