Paul Rosenberg in Alternet:

In my interview last week with political scientist Rachel Bitecofer, who predicted a 42-seat “blue wave” four months in advance, she also discussed the groundbreaking campaigns of Stacey Abrams and Beto O’Rourke, even though neither was elected. Neera Tanden, president of the Center for American Progress, offered a curious response on Twitter: “Stacey Abrams and Beto ran liberal campaigns, not hard left campaigns.” As Bitecofer replied, “I don’t advocate hard left campaigns, that’s not what my research argues.” She later added that “my thesis IS the Beto/Abrams turnout model, not something else.” Ideology wasn’t the issue she focused on — mobilizing base voters was. Tanden’s response is both curious and troubling because literally no one argues for “hard left” campaigns. As retired intelligence analyst James Scaminaci tweeted in the ensuing conversation: “Hard Left” is Marxists, Marxist-Leninist, Trotskyists, Leninists, Stalinists, Maoists, Spartacus League, Guevaras. Bernie, AOC, DSA, Warren, FDR ain’t “hard left.” If you use “HL,” you are grossly misinformed about left-wing politics. You might have missed the Cold War.”

In my interview last week with political scientist Rachel Bitecofer, who predicted a 42-seat “blue wave” four months in advance, she also discussed the groundbreaking campaigns of Stacey Abrams and Beto O’Rourke, even though neither was elected. Neera Tanden, president of the Center for American Progress, offered a curious response on Twitter: “Stacey Abrams and Beto ran liberal campaigns, not hard left campaigns.” As Bitecofer replied, “I don’t advocate hard left campaigns, that’s not what my research argues.” She later added that “my thesis IS the Beto/Abrams turnout model, not something else.” Ideology wasn’t the issue she focused on — mobilizing base voters was. Tanden’s response is both curious and troubling because literally no one argues for “hard left” campaigns. As retired intelligence analyst James Scaminaci tweeted in the ensuing conversation: “Hard Left” is Marxists, Marxist-Leninist, Trotskyists, Leninists, Stalinists, Maoists, Spartacus League, Guevaras. Bernie, AOC, DSA, Warren, FDR ain’t “hard left.” If you use “HL,” you are grossly misinformed about left-wing politics. You might have missed the Cold War.”

In short, “hard left” is a bogeyman term so far as American politics is concerned — one meant to put Democrats constantly on the defensive, either cowering or fighting with each other. It recalls the worst days of McCarthyism. Which is why I responded: Repeating right-wing frames is a no-no. It’s as simple as that. Tanden’s hardly the only one to do this, but she’s the president of the Center for American Progress, and closely associated with the leadership of the Democratic Party. CAP’s Think Progress blog has caught right-wingers using this attack phrase for years — like this entry, noting Newt Gingrich using it to smear legendary PBS journalist Bill Moyers. Tanden should know better. Not in spite of being a close ally and longtime supporter of Hillary Clinton, but because of it. After all, the right-wing media has used the “hard left” label to attack Clinton since August 1992, when the American Spectator ran a tone-setting attack story: “The Lady Macbeth of Little Rock: Hillary Clinton’s hard-left past and present.”

More here.

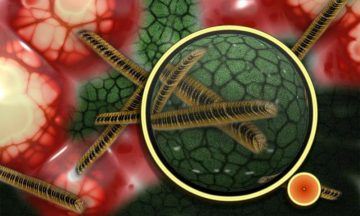

For ages, the best ways to treat cancer were surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, but in the last decade doctors have been working to harness patients’ own immune systems to fight cancer. One result is called chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy—CAR T for short—in which doctors remove T cells, which are central to the body’s immune response to disease, and modify them so they’re better prepared to attack cancer cells. CAR T has now been used to treat previously intractable cancers, including certain lymphomas that are the focus of the new study. Yet the treatment only works 30 to 40 percent of the time, said Andrew Rezvani, an assistant professor of medicine who is collaborating on the project. The rest of the time, CAR T’s effectiveness fades away over time or fails altogether.

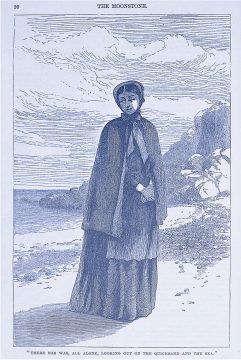

For ages, the best ways to treat cancer were surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, but in the last decade doctors have been working to harness patients’ own immune systems to fight cancer. One result is called chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy—CAR T for short—in which doctors remove T cells, which are central to the body’s immune response to disease, and modify them so they’re better prepared to attack cancer cells. CAR T has now been used to treat previously intractable cancers, including certain lymphomas that are the focus of the new study. Yet the treatment only works 30 to 40 percent of the time, said Andrew Rezvani, an assistant professor of medicine who is collaborating on the project. The rest of the time, CAR T’s effectiveness fades away over time or fails altogether. Like Collins’s earlier The Woman in White, The Moonstone employs a range of sensational plot twists and is narrated by an array of competing voices that variously draw on the reader’s sympathies and skepticism. But where The Woman in White relied on the investigative chops of an art teacher to unravel its mystery, The Moonstone introduces, for the first time in the British novel, the figure of the police investigator: Sergeant Cuff, the character who would set the standard for the new genre of the detective story. Archetypally whimsical and dandyish, Cuff sports a white cravat and a fondness for roses. “One of these days (please God) I shall retire from catching thieves,” he says early on, “and try my hand at growing roses.” Arriving on the scene of the crime, Cuff proceeds to meticulously reconstruct the diamond robbery. His search involves—what else—a close examination of everybody’s closets, “from her ladyship downwards.” No detail is too small to attract his attention, no aspect of domestic life too insignifi cant. Under the impersonal gaze of the detective, no one is beyond suspicion. At one point, Cuff even suspects Rachel of stealing the diamond—from herself. (She didn’t, but what a plot twist that would have been.)

Like Collins’s earlier The Woman in White, The Moonstone employs a range of sensational plot twists and is narrated by an array of competing voices that variously draw on the reader’s sympathies and skepticism. But where The Woman in White relied on the investigative chops of an art teacher to unravel its mystery, The Moonstone introduces, for the first time in the British novel, the figure of the police investigator: Sergeant Cuff, the character who would set the standard for the new genre of the detective story. Archetypally whimsical and dandyish, Cuff sports a white cravat and a fondness for roses. “One of these days (please God) I shall retire from catching thieves,” he says early on, “and try my hand at growing roses.” Arriving on the scene of the crime, Cuff proceeds to meticulously reconstruct the diamond robbery. His search involves—what else—a close examination of everybody’s closets, “from her ladyship downwards.” No detail is too small to attract his attention, no aspect of domestic life too insignifi cant. Under the impersonal gaze of the detective, no one is beyond suspicion. At one point, Cuff even suspects Rachel of stealing the diamond—from herself. (She didn’t, but what a plot twist that would have been.) Quichotte, the Booker Prize long-listed 14th novel from

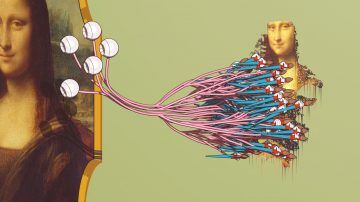

Quichotte, the Booker Prize long-listed 14th novel from  This is the great mystery of human vision: Vivid pictures of the world appear before our mind’s eye, yet the brain’s visual system receives very little information from the world itself. Much of what we “see” we conjure in our heads.

This is the great mystery of human vision: Vivid pictures of the world appear before our mind’s eye, yet the brain’s visual system receives very little information from the world itself. Much of what we “see” we conjure in our heads. All of us have been wrong about things from time to time. But sometimes it was a simple, forgivable mistake, while other times we really should have been correct. Properties that systematically prevent us from being correct, and for which we can legitimately be blamed, are “intellectual vices.” Examples might include closed-mindedness, wishful thinking, overconfidence, selective attention, and so on. Quassim Cassam is a philosopher who studies knowledge in various forms, and who has recently written a book

All of us have been wrong about things from time to time. But sometimes it was a simple, forgivable mistake, while other times we really should have been correct. Properties that systematically prevent us from being correct, and for which we can legitimately be blamed, are “intellectual vices.” Examples might include closed-mindedness, wishful thinking, overconfidence, selective attention, and so on. Quassim Cassam is a philosopher who studies knowledge in various forms, and who has recently written a book  Though earth scientists have yet to agree on the “

Though earth scientists have yet to agree on the “ I need to know more about Terezin, but I am afraid to go there. It’s only a fifty-minute train ride from Prague. Instead, I search for diaries and I find Gonda Redlich’s, translated from Hebrew into English by the late historian Saul S. Friedman. Gonda is a twenty-six-year-old who headed the children’s department at Terezin for three years and wrote regularly until his deportation to Auschwitz. I read at the office until it closes at eleven. I walk straight home, past roaming groups of drunken tourists, and continue to read in bed.

I need to know more about Terezin, but I am afraid to go there. It’s only a fifty-minute train ride from Prague. Instead, I search for diaries and I find Gonda Redlich’s, translated from Hebrew into English by the late historian Saul S. Friedman. Gonda is a twenty-six-year-old who headed the children’s department at Terezin for three years and wrote regularly until his deportation to Auschwitz. I read at the office until it closes at eleven. I walk straight home, past roaming groups of drunken tourists, and continue to read in bed. Stepping into Cole’s, one of the oldest restaurant-bars in Los Angeles, and the self-professed inventor of the French Dip sandwich, feels like stepping back in time to 1908, when the saloon first opened. It’s dimly lit inside, there are old wood-paneled walls, and a long bar greets you upon entry. On a quiet afternoon, you eat your sandwich, maybe have a drink or two, and then chances are you’ll eventually hit the restroom. If you’re in the men’s room, you might notice a bronze plaque bolted to the wall near the stalls: “CHARLES BUKOWSKI PISSED HERE.” People love to take pictures of it. On Instagram, it’s nearly as popular as shots of the sandwich that made Cole’s famous. In 2019,

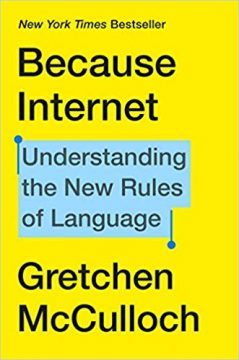

Stepping into Cole’s, one of the oldest restaurant-bars in Los Angeles, and the self-professed inventor of the French Dip sandwich, feels like stepping back in time to 1908, when the saloon first opened. It’s dimly lit inside, there are old wood-paneled walls, and a long bar greets you upon entry. On a quiet afternoon, you eat your sandwich, maybe have a drink or two, and then chances are you’ll eventually hit the restroom. If you’re in the men’s room, you might notice a bronze plaque bolted to the wall near the stalls: “CHARLES BUKOWSKI PISSED HERE.” People love to take pictures of it. On Instagram, it’s nearly as popular as shots of the sandwich that made Cole’s famous. In 2019,  Language is always changing, and on a macro level some of the most radical changes have resulted from technology. Writing is the prime example. Millennia after its development, telephony reshaped our communication; mere decades later, computers arrived, became networked, and here I am, typing something for you to read on your PC or phone, however many miles away.

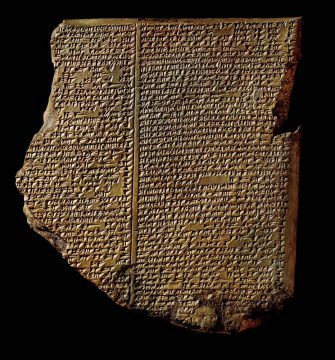

Language is always changing, and on a macro level some of the most radical changes have resulted from technology. Writing is the prime example. Millennia after its development, telephony reshaped our communication; mere decades later, computers arrived, became networked, and here I am, typing something for you to read on your PC or phone, however many miles away. Charles Darwin closed his On the Origin of Species (1870) with a provocative promise that ‘light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history’. In his later books The Descent of Man (1871) and The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Darwin shed some of that promised light, especially on the evolved emotional and cognitive capacities that humans shared with other mammals. In one scandalous passage, he demonstrated that four ‘defining’ characteristics of Homo sapiens – tool use, language, aesthetic sensitivity and religion – are all present, if rudimentary, in nonhuman animals. Even morality, he argued, arose through natural selection. Altruistic self-sacrifice might not give the individual a survival advantage, but, he wrote:

Charles Darwin closed his On the Origin of Species (1870) with a provocative promise that ‘light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history’. In his later books The Descent of Man (1871) and The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Darwin shed some of that promised light, especially on the evolved emotional and cognitive capacities that humans shared with other mammals. In one scandalous passage, he demonstrated that four ‘defining’ characteristics of Homo sapiens – tool use, language, aesthetic sensitivity and religion – are all present, if rudimentary, in nonhuman animals. Even morality, he argued, arose through natural selection. Altruistic self-sacrifice might not give the individual a survival advantage, but, he wrote: The spread of substate and transnational forms of terrorism that target ordinary civilians for mass murder tears at the social and political consensus in our country and across the world. The aim is to create the void that will usher in a new world, with no room for innocents on the other side, or in the “Gray Zone” between that includes most of humanity.

The spread of substate and transnational forms of terrorism that target ordinary civilians for mass murder tears at the social and political consensus in our country and across the world. The aim is to create the void that will usher in a new world, with no room for innocents on the other side, or in the “Gray Zone” between that includes most of humanity. Lawyers are one of America’s most

Lawyers are one of America’s most

THE RÉSUMÉ

THE RÉSUMÉ