Julian Barnes at the LRB:

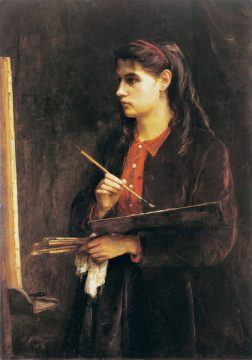

In 1865-68, Edma had painted a portrait of her sister: standing at the easel, brush in hand, in fiercely concentrating profile. It is a remarkably talented work, both as a character portrayal and as a construction. Berthe is wearing a plum-brown velvet coat over which her dark brown hair falls; underneath, there is a red blouse whose colour is picked up in her thin red headband. The tonality is generally dark, except for two fierce slashes of light. On the extreme left of the picture, the illuminated edge of Berthe’s canvas descends at a slight angle to the vertical. In the centre, a broader fall of light at the opposite angle illuminates a determined face, three white shirt buttons, the fingers of a painting hand and the whiteness of a dangling rag; it also falls, more discreetly, on the tip of her brush and the thin edge of her palette. The picture is rightly placed at the start of the Musée d’Orsay show, and has a double poignancy: internally, because it allows us to discern the strength of character which will make Berthe Morisot a true artist, even though she herself can’t. But also externally, because it is one of only two pictures by Edma to survive. At some point, and with what motivation we can only guess, she destroyed all her work except for this canvas and a landscape. The assertion of unfulfilled talent can often sound a little theoretical; but there is further evidence. In late 1873 Degas, who was helping to organise the First Impressionist Exhibition, wrote to Mme Morisot to seek her help in persuading Berthe to contribute: ‘We think Mlle Berthe Morisot’s name and talent are too important to us to do without,’ he writes.

more here.

Written by one brilliant writer about another, this remarkable book is, in part, about the craft of writing. But in the main, it’s an account of author Lawrence Weschler’s friendship with Oliver Sacks, a man whom he describes as “impressively erudite and impossibly cuddly.” Sacks comes across as singular. For many years, he lived by himself on City Island, not far from Manhattan, in a house he acquired when he swam out there, saw a house he liked, learned that it was for sale, and bought it that afternoon, his wet trunks dripping in the real estate agent’s office. He regularly swam for miles in the ocean, sometimes late at night. He loved cuttlefish and motorcycles, which he rode, drug-fueled, up and down the California coast when he was a neurology resident at UCLA. A friend of his from that time recalled, “Oliver wouldn’t behave, he wouldn’t follow rules, he’d eat the leftover food off the patients’ trays during rounds, and he drove them nuts.”

Written by one brilliant writer about another, this remarkable book is, in part, about the craft of writing. But in the main, it’s an account of author Lawrence Weschler’s friendship with Oliver Sacks, a man whom he describes as “impressively erudite and impossibly cuddly.” Sacks comes across as singular. For many years, he lived by himself on City Island, not far from Manhattan, in a house he acquired when he swam out there, saw a house he liked, learned that it was for sale, and bought it that afternoon, his wet trunks dripping in the real estate agent’s office. He regularly swam for miles in the ocean, sometimes late at night. He loved cuttlefish and motorcycles, which he rode, drug-fueled, up and down the California coast when he was a neurology resident at UCLA. A friend of his from that time recalled, “Oliver wouldn’t behave, he wouldn’t follow rules, he’d eat the leftover food off the patients’ trays during rounds, and he drove them nuts.” Brexit

Brexit A

A In 1906, Dutch writer Maarten Maartens—acclaimed in his lifetime but now mostly forgotten—published a surreal, satirical novel called The Healers. The book centers on one Professor Lisse, who has conjured up a potential bioweapon: the Semicolon Bacillus, an “especial variety of the Comma.” The doctor has killed hundreds of rabbits demonstrating the Semicolon’s toxicity, but, at the beginning of the novel, he hasn’t yet succeeded in getting his punctuation past the human immune system, which destroys Semicolons instantly as soon as they enter the mouth.

In 1906, Dutch writer Maarten Maartens—acclaimed in his lifetime but now mostly forgotten—published a surreal, satirical novel called The Healers. The book centers on one Professor Lisse, who has conjured up a potential bioweapon: the Semicolon Bacillus, an “especial variety of the Comma.” The doctor has killed hundreds of rabbits demonstrating the Semicolon’s toxicity, but, at the beginning of the novel, he hasn’t yet succeeded in getting his punctuation past the human immune system, which destroys Semicolons instantly as soon as they enter the mouth. Physicists study systems that are sufficiently simple that it’s possible to find deep unifying principles applicable to all situations. In psychology or sociology that’s a lot harder. But as I say at the end of this episode, Mindscape is a safe space for grand theories of everything. Psychologist Michele Gelfand claims that there’s a single dimension that captures a lot about how cultures differ: a spectrum between “tight” and “loose,” referring to the extent to which social norms are automatically respected. Oregon is loose; Alabama is tight. Italy is loose; Singapore is tight. It’s a provocative thesis, back up by copious amounts of data, that could shed light on human behavior not only in different parts of the world, but in different settings at work or at school.

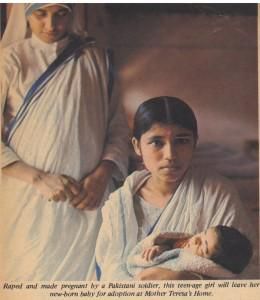

Physicists study systems that are sufficiently simple that it’s possible to find deep unifying principles applicable to all situations. In psychology or sociology that’s a lot harder. But as I say at the end of this episode, Mindscape is a safe space for grand theories of everything. Psychologist Michele Gelfand claims that there’s a single dimension that captures a lot about how cultures differ: a spectrum between “tight” and “loose,” referring to the extent to which social norms are automatically respected. Oregon is loose; Alabama is tight. Italy is loose; Singapore is tight. It’s a provocative thesis, back up by copious amounts of data, that could shed light on human behavior not only in different parts of the world, but in different settings at work or at school. The post- Liberation War generation of Bangladesh know stories from 1971 all too well. Our families are framed and bound by the history of this war. What Bangladeshi family has not been touched by the passion, famine, murders and blood that gave birth to a new nation as it seceded from Pakistan? Bangladesh was one of the only successful nationalist movements post-

The post- Liberation War generation of Bangladesh know stories from 1971 all too well. Our families are framed and bound by the history of this war. What Bangladeshi family has not been touched by the passion, famine, murders and blood that gave birth to a new nation as it seceded from Pakistan? Bangladesh was one of the only successful nationalist movements post- C

C IT BEGINS THE WAY

IT BEGINS THE WAY A

A In September 1798 a self-published book with an outlandish premise was about to change the world. At first sight, “An Inquiry into the Cowpox” looked more like a piece of vanity publishing than one of the greatest landmarks in the history of medicine. Its author, a doctor called Edward Jenner, was largely unknown outside rural Gloucestershire. In a 75-page illustrated manual, Jenner explained how people could protect themselves from smallpox – a horrific brute of a disease that killed one person in 12 and left many survivors scarred for life – by inoculating themselves with cowpox, an obscure disease that affected cattle. This extraordinary process was to be known as vaccination, from the Latin for cow.

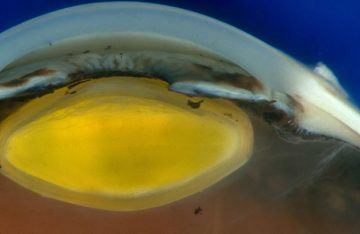

In September 1798 a self-published book with an outlandish premise was about to change the world. At first sight, “An Inquiry into the Cowpox” looked more like a piece of vanity publishing than one of the greatest landmarks in the history of medicine. Its author, a doctor called Edward Jenner, was largely unknown outside rural Gloucestershire. In a 75-page illustrated manual, Jenner explained how people could protect themselves from smallpox – a horrific brute of a disease that killed one person in 12 and left many survivors scarred for life – by inoculating themselves with cowpox, an obscure disease that affected cattle. This extraordinary process was to be known as vaccination, from the Latin for cow. A Japanese woman in her forties has become the first person in the world to have her cornea repaired using reprogrammed stem cells. At a press conference on 29 August, ophthalmologist Kohji Nishida from Osaka University, Japan, said the woman has a disease in which the stem cells that repair the cornea, a transparent layer that covers and protects the eye, are lost. The condition makes vision blurry and can lead to blindness.

A Japanese woman in her forties has become the first person in the world to have her cornea repaired using reprogrammed stem cells. At a press conference on 29 August, ophthalmologist Kohji Nishida from Osaka University, Japan, said the woman has a disease in which the stem cells that repair the cornea, a transparent layer that covers and protects the eye, are lost. The condition makes vision blurry and can lead to blindness. It is hard work to write a book, so there is unavoidable irony in fashioning a volume on the value of being idle. There is a paradox, too: to praise idleness is to suggest that there is some point to it, that wasting time is not a waste of time. Paradox infuses the experience of being idle. Rapturous relaxation can be difficult to distinguish from melancholy. When the academic year comes to an end, I find myself sprawled on the couch, re-watching old episodes of British comedy panel shows on a loop. I cannot tell if I am depressed or taking an indulgent break. As Samuel Johnson wrote: “Every man is, or hopes to be, an Idler.” As he also wrote: “There are … miseries in idleness, which the Idler only can conceive.”

It is hard work to write a book, so there is unavoidable irony in fashioning a volume on the value of being idle. There is a paradox, too: to praise idleness is to suggest that there is some point to it, that wasting time is not a waste of time. Paradox infuses the experience of being idle. Rapturous relaxation can be difficult to distinguish from melancholy. When the academic year comes to an end, I find myself sprawled on the couch, re-watching old episodes of British comedy panel shows on a loop. I cannot tell if I am depressed or taking an indulgent break. As Samuel Johnson wrote: “Every man is, or hopes to be, an Idler.” As he also wrote: “There are … miseries in idleness, which the Idler only can conceive.” “The so-called ‘female’ brain,” says Rippon, “has suffered centuries of being described as undersized, underdeveloped, evolutionarily inferior, poorly organised and generally defective.” Such assertions were, and still are, so widespread that Rippon admits feeling as though she’s playing “Whac-a-Mole”. She has barely disproved the newest study professing to demonstrate how men and women’s brains differ, when another is published.

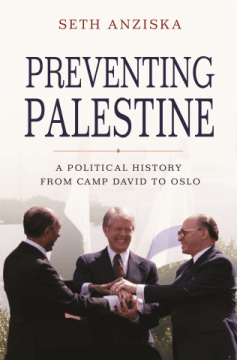

“The so-called ‘female’ brain,” says Rippon, “has suffered centuries of being described as undersized, underdeveloped, evolutionarily inferior, poorly organised and generally defective.” Such assertions were, and still are, so widespread that Rippon admits feeling as though she’s playing “Whac-a-Mole”. She has barely disproved the newest study professing to demonstrate how men and women’s brains differ, when another is published. In early June 2018, in an interview to the BBC in London, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu seemed relaxed and upbeat. Sitting in a room overlooking the river Thames, he celebrated the newfound cooperation between Israel and Arab states, hinting at Israel’s strengthening relationship with Gulf states. When asked about relations with the Palestinians, Netanyahu was less enthusiastic. He blamed Palestinian leadership for refusing negotiations. Prompted to spell out his vision for a peaceful resolution of the century-old Israel-Palestine conflict, he proposed a model in which “they’ll have all the rights to govern themselves, and none of the powers to threaten us […] we would have the overriding security responsibility.” Would this be a Palestinian state? Netanyahu deflected: “state minus, autonomy plus – I don’t care how you call it.” He dismissed the notion that the West Bank was Occupied Palestinian territory. “Who says it’s their land?” As for the relevance of international law, Netanyahu scoffed “I don’t buy current fads.”

In early June 2018, in an interview to the BBC in London, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu seemed relaxed and upbeat. Sitting in a room overlooking the river Thames, he celebrated the newfound cooperation between Israel and Arab states, hinting at Israel’s strengthening relationship with Gulf states. When asked about relations with the Palestinians, Netanyahu was less enthusiastic. He blamed Palestinian leadership for refusing negotiations. Prompted to spell out his vision for a peaceful resolution of the century-old Israel-Palestine conflict, he proposed a model in which “they’ll have all the rights to govern themselves, and none of the powers to threaten us […] we would have the overriding security responsibility.” Would this be a Palestinian state? Netanyahu deflected: “state minus, autonomy plus – I don’t care how you call it.” He dismissed the notion that the West Bank was Occupied Palestinian territory. “Who says it’s their land?” As for the relevance of international law, Netanyahu scoffed “I don’t buy current fads.” About 70 percent of Americans

About 70 percent of Americans  Greta Thunberg, the Swedish teenager who inspired the now-global movement, has become a primary target. On Wednesday, the 16-year-old arrived in New York after completing her voyage across the Atlantic aboard an environmentally friendly yacht. She faced a barrage of attacks on the way. “Freak yachting accidents do happen in August,”

Greta Thunberg, the Swedish teenager who inspired the now-global movement, has become a primary target. On Wednesday, the 16-year-old arrived in New York after completing her voyage across the Atlantic aboard an environmentally friendly yacht. She faced a barrage of attacks on the way. “Freak yachting accidents do happen in August,”