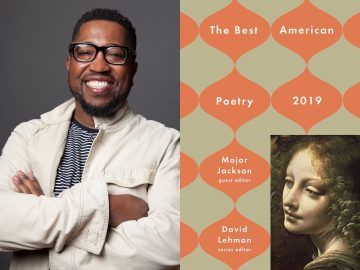

Major Jackson at The Paris Review:

Poems have reacquainted me with the spectacular spirit of the human, that which is fundamentally elusive to algorithms, artificial intelligence, behavioral science, and genetic research: “Sometimes I get up early and even my soul is wet” (Pablo Neruda, “Here I Love You”); “Earth’s the right place for love: / I don’t know where it’s likely to go better” (Robert Frost, “Birches”); “I wonder what death tastes like. / Sometimes I toss the butterflies / Back into the air” (Yusef Komunyakaa, “Venus’s Flytrap”); “The world / is flux, and light becomes what it touches” (Lisel Mueller, “Monet Refuses the Operation”); “We do not want them to have less. / But it is only natural that we should think we have not enough” (Gwendolyn Brooks, “Beverly Hills, Chicago”). Once, while in graduate school, reading Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” in the corner of a café, I was surprised to find myself with brimming eyes, filled with unspeakable wonder and sadness at the veracity of his words: “Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: / The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star, / Hath had elsewhere its setting, / And cometh from afar.” Poetry, as the poet Edward Hirsch has written, “speaks out of a solitude to a solitude.”

Poems have reacquainted me with the spectacular spirit of the human, that which is fundamentally elusive to algorithms, artificial intelligence, behavioral science, and genetic research: “Sometimes I get up early and even my soul is wet” (Pablo Neruda, “Here I Love You”); “Earth’s the right place for love: / I don’t know where it’s likely to go better” (Robert Frost, “Birches”); “I wonder what death tastes like. / Sometimes I toss the butterflies / Back into the air” (Yusef Komunyakaa, “Venus’s Flytrap”); “The world / is flux, and light becomes what it touches” (Lisel Mueller, “Monet Refuses the Operation”); “We do not want them to have less. / But it is only natural that we should think we have not enough” (Gwendolyn Brooks, “Beverly Hills, Chicago”). Once, while in graduate school, reading Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” in the corner of a café, I was surprised to find myself with brimming eyes, filled with unspeakable wonder and sadness at the veracity of his words: “Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: / The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star, / Hath had elsewhere its setting, / And cometh from afar.” Poetry, as the poet Edward Hirsch has written, “speaks out of a solitude to a solitude.”

more here.

The climate of South Asia is not kind to ancient DNA. It is hot and it rains. In monsoon season, water seeps into ancient bones in the ground, degrading the old genetic material. So by the time archeologists and geneticists finally got DNA out of a tiny ear bone from a 4,000-plus-year-old skeleton, they had already tried dozens of samples—all from cemeteries of the mysterious Indus Valley civilization, all without any success. The Indus Valley civilization, also known as the Harappan civilization, flourished 4,000 years ago in what is now India and Pakistan. It surpassed its contemporaries, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, in size. Its trade routes stretched thousands of miles. It had agriculture and planned cities and sewage systems. And then, it disappeared. “The Indus Valley civilization has been an enigma for South Asians. We read about it in our textbooks,” says

The climate of South Asia is not kind to ancient DNA. It is hot and it rains. In monsoon season, water seeps into ancient bones in the ground, degrading the old genetic material. So by the time archeologists and geneticists finally got DNA out of a tiny ear bone from a 4,000-plus-year-old skeleton, they had already tried dozens of samples—all from cemeteries of the mysterious Indus Valley civilization, all without any success. The Indus Valley civilization, also known as the Harappan civilization, flourished 4,000 years ago in what is now India and Pakistan. It surpassed its contemporaries, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, in size. Its trade routes stretched thousands of miles. It had agriculture and planned cities and sewage systems. And then, it disappeared. “The Indus Valley civilization has been an enigma for South Asians. We read about it in our textbooks,” says  Over the past two centuries, millions of dedicated people – revolutionaries, activists, politicians, and theorists – have yet to curb the disastrous and increasingly globalised trajectory of economic polarisation and ecological degradation. Perhaps because we are utterly trapped in flawed ways of thinking about technology and economy – as the current discourse on climate change shows. Rising greenhouse gas emissions are not just generating climate change. They are giving more and more of us climate anxiety –

Over the past two centuries, millions of dedicated people – revolutionaries, activists, politicians, and theorists – have yet to curb the disastrous and increasingly globalised trajectory of economic polarisation and ecological degradation. Perhaps because we are utterly trapped in flawed ways of thinking about technology and economy – as the current discourse on climate change shows. Rising greenhouse gas emissions are not just generating climate change. They are giving more and more of us climate anxiety –

“Correlation is not causation.”

“Correlation is not causation.”

In the early 1950s, a young economist named Paul Volcker worked as a human calculator in an office deep inside the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. He crunched numbers for the people who made decisions, and he told his wife that he saw little chance of ever moving up. The central bank’s leadership included bankers, lawyers and an Iowa hog farmer, but not a single economist. The Fed’s chairman, a former stockbroker named William McChesney Martin, once told a visitor that he kept a small staff of economists in the basement of the Fed’s Washington headquarters. They were in the building, he said, because they asked good questions. They were in the basement because “they don’t know their own limitations.”

In the early 1950s, a young economist named Paul Volcker worked as a human calculator in an office deep inside the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. He crunched numbers for the people who made decisions, and he told his wife that he saw little chance of ever moving up. The central bank’s leadership included bankers, lawyers and an Iowa hog farmer, but not a single economist. The Fed’s chairman, a former stockbroker named William McChesney Martin, once told a visitor that he kept a small staff of economists in the basement of the Fed’s Washington headquarters. They were in the building, he said, because they asked good questions. They were in the basement because “they don’t know their own limitations.” To read Käsebier Takes Berlin today, more than 80 years after its original publication, is to experience occasional shocks of recognition. Many have noted the similarities between Weimar-era Germany and the Trump-era United States, and in Käsebier, these parallels sometimes come to the fore. As Duvernoy notes in her introduction, the rise of Käsebier is, in effect, the result of a story gone viral. In one passage, we come across the phrase “fake news.” In another, Miermann expresses something similar to the news fatigue so many Americans feel: “I’m always supposed to get worked up: against sales taxes, for sales taxes, against excise taxes, for excise taxes. I’m not going to get worked up again until five o’clock tomorrow unless a beautiful girl walks into the room!”

To read Käsebier Takes Berlin today, more than 80 years after its original publication, is to experience occasional shocks of recognition. Many have noted the similarities between Weimar-era Germany and the Trump-era United States, and in Käsebier, these parallels sometimes come to the fore. As Duvernoy notes in her introduction, the rise of Käsebier is, in effect, the result of a story gone viral. In one passage, we come across the phrase “fake news.” In another, Miermann expresses something similar to the news fatigue so many Americans feel: “I’m always supposed to get worked up: against sales taxes, for sales taxes, against excise taxes, for excise taxes. I’m not going to get worked up again until five o’clock tomorrow unless a beautiful girl walks into the room!” Baths are very comforting: gentler, calmer than showers. The slow clean. For a while, though, across a patch of nervous books in the mid-twentieth century, baths were troublesome. They were prone to intrusion and disorder. They were too hot, too small, too crowded with litanies of junk: newspapers, cigarettes, alcohol, razors.

Baths are very comforting: gentler, calmer than showers. The slow clean. For a while, though, across a patch of nervous books in the mid-twentieth century, baths were troublesome. They were prone to intrusion and disorder. They were too hot, too small, too crowded with litanies of junk: newspapers, cigarettes, alcohol, razors. The great service done by Mitchell Zuckoff in Fall and Rise is to document in minute but telling detail the innumerable human tragedies that unfolded in the space of a few hours on the morning of 11 September 2001.

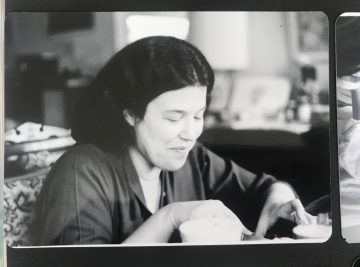

The great service done by Mitchell Zuckoff in Fall and Rise is to document in minute but telling detail the innumerable human tragedies that unfolded in the space of a few hours on the morning of 11 September 2001. In November 1959 aged 26,

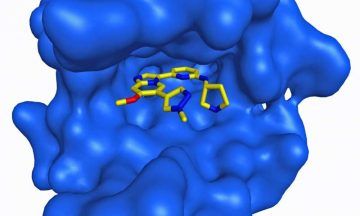

In November 1959 aged 26,  Scientists from the National Institutes of Health and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center have devised a potential treatment against a common type of leukemia that could have implications for many other types of cancer. The new approach takes aim at a way that cancer cells evade the effects of drugs, a process called adaptive resistance. The researchers, in a range of studies, identified a cellular pathway that allows a form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a deadly blood and bone marrow

Scientists from the National Institutes of Health and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center have devised a potential treatment against a common type of leukemia that could have implications for many other types of cancer. The new approach takes aim at a way that cancer cells evade the effects of drugs, a process called adaptive resistance. The researchers, in a range of studies, identified a cellular pathway that allows a form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a deadly blood and bone marrow  Mario Seccareccia and Marc Lavoie over at INET:

Mario Seccareccia and Marc Lavoie over at INET:

The people of Jammu and Kashmir on both sides of the border have been continuously betrayed by the governments of Pakistan and India.

The people of Jammu and Kashmir on both sides of the border have been continuously betrayed by the governments of Pakistan and India. Last night I was talking with our mutual friend S, and she said, “I always wanted to hear what Ann would say. She would listen to others present arguments, and then, when it was her turn to speak, she would find the beautiful bits in what she’d heard and put it all back together in a way that was brilliant and original and made people think she was extending their ideas.”

Last night I was talking with our mutual friend S, and she said, “I always wanted to hear what Ann would say. She would listen to others present arguments, and then, when it was her turn to speak, she would find the beautiful bits in what she’d heard and put it all back together in a way that was brilliant and original and made people think she was extending their ideas.”