Sarah Poole in University of Virginia Magazine:

Fredson Bowers didn’t know what he would find when he began digging into the disordered stack of 230 loose pages—all from 19th-century Walt Whitman manuscripts—that landed on his desk in 1951.

Fredson Bowers didn’t know what he would find when he began digging into the disordered stack of 230 loose pages—all from 19th-century Walt Whitman manuscripts—that landed on his desk in 1951.

But for Bowers, a revered UVA English professor, the papers formed a massive puzzle waiting to be fit together. They were an “opportunity for literary detective work … that was of the highest interest to attempt,” he wrote in 1959.

Bowers solved the puzzle—or part of it—when he discovered within that pile the unpublished original sequence for 12 poems, together called “Live Oak, with Moss,” that were distributed throughout a section of the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass.

The revelation of that sequence, illuminated by Bowers’ painstaking research, opened a door to insights that would change the way scholars looked at Whitman.

Unlike most of his work, “Live Oak” addresses themes of love. Scholars believe Whitman wrote the sequence after a relationship with a man named Fred Vaughan.

More here.

In 2010, physicists in Germany

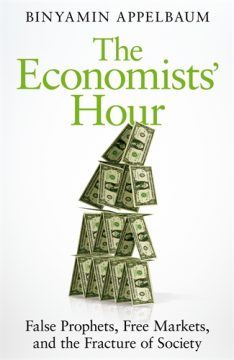

In 2010, physicists in Germany  Binyamin Appelbaum’s new book has lived up to its controversial billing, particularly among its subjects. The book condemns the role the economics profession has played in breeding inequality, and holds economists to account for the resulting backlash of xenophobic white nationalism. When the New York Times published

Binyamin Appelbaum’s new book has lived up to its controversial billing, particularly among its subjects. The book condemns the role the economics profession has played in breeding inequality, and holds economists to account for the resulting backlash of xenophobic white nationalism. When the New York Times published  Viola’s film I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like (1986), its title a loose translation of a Sanskrit verse from the Rig-Veda, serves as the intellectual and spiritual touchstone of the exhibit. Eighty-nine minutes long, it unfolds as a wordless odyssey, an epic quest for self-understanding and transcendence that ranges from mountain lakes and underground caves to grassy fields and remote islands. Viola contemplates the cryptic gazes of wild animals (mostly fish and birds, but also a pair of bison, a zebra, and an elephant); takes us inside his studio (playfully modeled on seventeenth-century Dutch still-lifes); leads us through an intense, violent sequence filled with split-second flashes of lightning, crowded highways, and roaring flames; then drops us down in the middle of a raucous firewalking ritual in Fiji, the soundtrack filled with beating drums and wailing wind instruments. The film concludes in a forest, close to the lake where we began.

Viola’s film I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like (1986), its title a loose translation of a Sanskrit verse from the Rig-Veda, serves as the intellectual and spiritual touchstone of the exhibit. Eighty-nine minutes long, it unfolds as a wordless odyssey, an epic quest for self-understanding and transcendence that ranges from mountain lakes and underground caves to grassy fields and remote islands. Viola contemplates the cryptic gazes of wild animals (mostly fish and birds, but also a pair of bison, a zebra, and an elephant); takes us inside his studio (playfully modeled on seventeenth-century Dutch still-lifes); leads us through an intense, violent sequence filled with split-second flashes of lightning, crowded highways, and roaring flames; then drops us down in the middle of a raucous firewalking ritual in Fiji, the soundtrack filled with beating drums and wailing wind instruments. The film concludes in a forest, close to the lake where we began. The book is “an autobiographical account of what it is like to have a body in a specific time and place,” to borrow Boyer’s description of Hieroi Logoi (Sacred Tales) by the second-century Greek orator Aelius Aristides, one of many texts and artworks about illness and pain that Boyer references, quotes from, and argues with, placing her writing in their lineage. The prologue to The Undying explains what makes her specific time and place—and the literary forms they demand—different from those of breast cancer patients who came before. When Fanny Burney described her pre-anesthesia mastectomy in a 1812 letter to her sister, she was articulating a rare experience at the great personal cost of reliving the nearly unbearable. When Audre Lorde’s Cancer Journals were published in 1980, her first-person account of cancer rippled through a surrounding quiet. Until more recently, people didn’t often discuss their diagnoses in public. Susan Sontag and Rachel Carson each had breast cancer, yet wrote about cancer without addressing their own.

The book is “an autobiographical account of what it is like to have a body in a specific time and place,” to borrow Boyer’s description of Hieroi Logoi (Sacred Tales) by the second-century Greek orator Aelius Aristides, one of many texts and artworks about illness and pain that Boyer references, quotes from, and argues with, placing her writing in their lineage. The prologue to The Undying explains what makes her specific time and place—and the literary forms they demand—different from those of breast cancer patients who came before. When Fanny Burney described her pre-anesthesia mastectomy in a 1812 letter to her sister, she was articulating a rare experience at the great personal cost of reliving the nearly unbearable. When Audre Lorde’s Cancer Journals were published in 1980, her first-person account of cancer rippled through a surrounding quiet. Until more recently, people didn’t often discuss their diagnoses in public. Susan Sontag and Rachel Carson each had breast cancer, yet wrote about cancer without addressing their own. How to affirm life in the face of suffering, sacrifice and likely failure may have the structure of a question, but, like the apparent questions of who we are and what we are here for, it is far from obvious that what we are meant to do with it is to search for an answer, let alone settle on one. To affirm life is not to give a theoretical justification of life, to acknowledge its merits and counter the charges of its detractors. To affirm life is to live, and to do so in a certain way: committing to projects and relationships, assuming responsibility, allowing things to matter to you. Bringing a child into the world is not the only way to affirm life—Heti’s narrator, for one, chooses art—but it is the most basic. This is not only because bringing forth and nurturing life is the most literal way of affirming it, but because parenting is the greatest responsibility a human can bear toward another.

How to affirm life in the face of suffering, sacrifice and likely failure may have the structure of a question, but, like the apparent questions of who we are and what we are here for, it is far from obvious that what we are meant to do with it is to search for an answer, let alone settle on one. To affirm life is not to give a theoretical justification of life, to acknowledge its merits and counter the charges of its detractors. To affirm life is to live, and to do so in a certain way: committing to projects and relationships, assuming responsibility, allowing things to matter to you. Bringing a child into the world is not the only way to affirm life—Heti’s narrator, for one, chooses art—but it is the most basic. This is not only because bringing forth and nurturing life is the most literal way of affirming it, but because parenting is the greatest responsibility a human can bear toward another. To be a

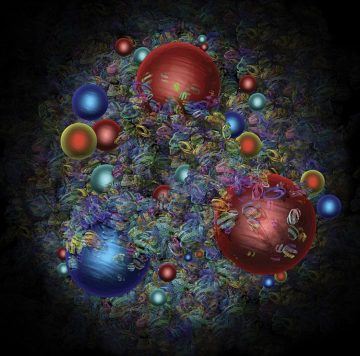

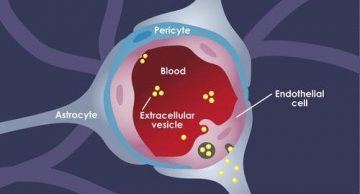

To be a  Metastasizing breast cancers typically seek out the bones, lung, and brain. Brain metastases are especially dangerous; many women survive for less than a year after diagnosis. How is the cancer able to get past the blood brain barrier? And can it be blocked? Those questions led Ph.D. candidate Golnaz Morad, DDS, and her mentor Marsha Moses, Ph.D., to conduct an in-depth investigation of exosomes, also known as extracellular vesicles or EVs, and their role in breast-to-

Metastasizing breast cancers typically seek out the bones, lung, and brain. Brain metastases are especially dangerous; many women survive for less than a year after diagnosis. How is the cancer able to get past the blood brain barrier? And can it be blocked? Those questions led Ph.D. candidate Golnaz Morad, DDS, and her mentor Marsha Moses, Ph.D., to conduct an in-depth investigation of exosomes, also known as extracellular vesicles or EVs, and their role in breast-to- Mainstream philosophy and science at least since Aristotle have held to the view that each living body, under normal circumstances, should be inhabited by no more than one soul. If you don’t care for talk of souls, exchange that word for “individual”, and the point still stands: sharing bodily space is abnormal, a sign of pathology, to be corrected by flushing the worms out of your entrails, or by mulesing your sheep against flystrike.

Mainstream philosophy and science at least since Aristotle have held to the view that each living body, under normal circumstances, should be inhabited by no more than one soul. If you don’t care for talk of souls, exchange that word for “individual”, and the point still stands: sharing bodily space is abnormal, a sign of pathology, to be corrected by flushing the worms out of your entrails, or by mulesing your sheep against flystrike.

The Beatles

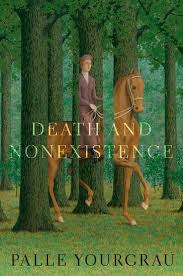

The Beatles To choose another prominent example, consider what Francis Kamm writes in Morality, Mortality: “Life can sometimes be worse for a person than the alternative of nonexistence, even though nonexistence is not a better state of being.” For Kamm, nonexistence is never a better state of being than is existence because for her, apparently, nonexistence is not a state of being at all.

To choose another prominent example, consider what Francis Kamm writes in Morality, Mortality: “Life can sometimes be worse for a person than the alternative of nonexistence, even though nonexistence is not a better state of being.” For Kamm, nonexistence is never a better state of being than is existence because for her, apparently, nonexistence is not a state of being at all. “The Odyssey” by Homer

“The Odyssey” by Homer Whether you’re talking about the polyrhythmic complexity of bands like the Talking Heads, the understated virtuosity of Television’s Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine, or even the deep chops of drummer Marc “Marky Ramone” Bell (Dust, Voidoids, Ramones), the punk scene was a wellspring of talent. Punk’s focus, for the most part, was song-centric and eschewed extended jamming, and the scene’s musicians prized restraint, as opposed to flash. But ability—despite their short hair, leather, and safety pins—wasn’t lacking. They were a reaction to the milquetoast fluff on popular radio (Debbie Boone, the Eagles), and took pains to distinguish themselves as misfits. But even the punks had their outliers, and a prominent delegate was guitarist Robert Quine.

Whether you’re talking about the polyrhythmic complexity of bands like the Talking Heads, the understated virtuosity of Television’s Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine, or even the deep chops of drummer Marc “Marky Ramone” Bell (Dust, Voidoids, Ramones), the punk scene was a wellspring of talent. Punk’s focus, for the most part, was song-centric and eschewed extended jamming, and the scene’s musicians prized restraint, as opposed to flash. But ability—despite their short hair, leather, and safety pins—wasn’t lacking. They were a reaction to the milquetoast fluff on popular radio (Debbie Boone, the Eagles), and took pains to distinguish themselves as misfits. But even the punks had their outliers, and a prominent delegate was guitarist Robert Quine. If every philosopher has a home that is not a house – the mountains, the sea, the city streets – for Martin Heidegger, it was the Black Forest. This sprawling woodland, situated by the French border in south-west Germany, imbued Heidegger’s language – his writings are filled with references to “forest paths”, “waymarks” and “clearings” – and shaped his thought. There, in the solitude of his small wood cabin, he wrote his great work, Being and Time.

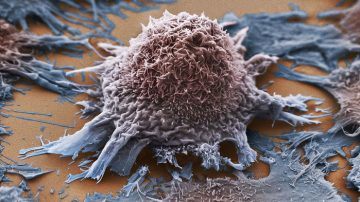

If every philosopher has a home that is not a house – the mountains, the sea, the city streets – for Martin Heidegger, it was the Black Forest. This sprawling woodland, situated by the French border in south-west Germany, imbued Heidegger’s language – his writings are filled with references to “forest paths”, “waymarks” and “clearings” – and shaped his thought. There, in the solitude of his small wood cabin, he wrote his great work, Being and Time. Cancer drug developers may be missing their molecular targets—and never knowing it. Many recent drugs take aim at specific cell proteins that drive the growth of tumors. The strategy has had marked successes, such as the leukemia drug Gleevec. But a study now finds that numerous candidate anticancer drugs still kill tumor cells after the genome editor CRISPR was used to eliminate their presumed targets. That suggests the drugs thwart cancer by interacting with different molecules than intended. The study,

Cancer drug developers may be missing their molecular targets—and never knowing it. Many recent drugs take aim at specific cell proteins that drive the growth of tumors. The strategy has had marked successes, such as the leukemia drug Gleevec. But a study now finds that numerous candidate anticancer drugs still kill tumor cells after the genome editor CRISPR was used to eliminate their presumed targets. That suggests the drugs thwart cancer by interacting with different molecules than intended. The study,  You started out being dismissed by the literary establishment as a lowly peddler of cheap horror. You’re now a lauded national treasure. How does it feel to be respectable?

You started out being dismissed by the literary establishment as a lowly peddler of cheap horror. You’re now a lauded national treasure. How does it feel to be respectable?