Christof Koch in Nautilus:

The contrast could not have been starker—here was one of the world’s most revered figures, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, expressing his belief that all life is sentient, while I, as a card-carrying neuroscientist, presented the contemporary Western consensus that some animals might, perhaps, possibly, share the precious gift of sentience, of conscious experience, with humans. The setting was a symposium between Buddhist monk-scholars and Western scientists in a Tibetan monastery in Southern India, fostering a dialogue in physics, biology, and brain science. Buddhism has philosophical traditions reaching back to the fifth century B.C. It defines life as possessing heat (i.e., a metabolism) and sentience, that is, the ability to sense, to experience, and to act. According to its teachings, consciousness is accorded to all animals, large and small—human adults and fetuses, monkeys, dogs, fish, and even lowly cockroaches and mosquitoes. All of them can suffer; all their lives are precious.

The contrast could not have been starker—here was one of the world’s most revered figures, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, expressing his belief that all life is sentient, while I, as a card-carrying neuroscientist, presented the contemporary Western consensus that some animals might, perhaps, possibly, share the precious gift of sentience, of conscious experience, with humans. The setting was a symposium between Buddhist monk-scholars and Western scientists in a Tibetan monastery in Southern India, fostering a dialogue in physics, biology, and brain science. Buddhism has philosophical traditions reaching back to the fifth century B.C. It defines life as possessing heat (i.e., a metabolism) and sentience, that is, the ability to sense, to experience, and to act. According to its teachings, consciousness is accorded to all animals, large and small—human adults and fetuses, monkeys, dogs, fish, and even lowly cockroaches and mosquitoes. All of them can suffer; all their lives are precious.

Compare this all-encompassing attitude of reverence to the historic view in the West. Abrahamic religions preach human exceptionalism—although animals have sensibilities, drives, and motivations and can act intelligently, they do not have an immortal soul that marks them as special, as able to be resurrected beyond history, in the Eschaton. On my travels and public talks, I still encounter plenty of scientists and others who, explicitly or implicitly, hold to human exclusivity. Cultural mores change slowly, and early childhood religious imprinting is powerful. I grew up in a devout Roman Catholic family with Purzel, a fearless dachshund. Purzel could be affectionate, curious, playful, aggressive, ashamed, or anxious. Yet my church taught that dogs do not have souls. Only humans do. Even as a child, I felt intuitively that this was wrong; either we all have souls, whatever that means, or none of us do.

René Descartes famously argued that a dog howling pitifully when hit by a carriage does not feel pain. The dog is simply a broken machine, devoid of the res cogitans or cognitive substance that is the hallmark of people. For those who argue that Descartes didn’t truly believe that dogs and other animals had no feelings, I present the fact that he, like other natural philosophers of his age, performed vivisection on rabbits and dogs. That’s live coronary surgery without anything to dull the agonizing pain. As much as I admire Descartes as a revolutionary thinker, I find this difficult to stomach.

More here.

Gagliano concluded, in a study published in a 2014 edition of Oecologia, that the shameplants had “remembered” that their being dropped from such a low height wasn’t actually a danger and realized they didn’t need to defend themselves. She believed that her experiment helped prove that “brains and neurons are a sophisticated solution but not a necessary requirement for learning.” The plants, she reasoned, were learning. The plants, she believed, were remembering. Bees, for instance, forget what they’ve learned after just a few days. These shameplants had remembered for nearly a month.

Gagliano concluded, in a study published in a 2014 edition of Oecologia, that the shameplants had “remembered” that their being dropped from such a low height wasn’t actually a danger and realized they didn’t need to defend themselves. She believed that her experiment helped prove that “brains and neurons are a sophisticated solution but not a necessary requirement for learning.” The plants, she reasoned, were learning. The plants, she believed, were remembering. Bees, for instance, forget what they’ve learned after just a few days. These shameplants had remembered for nearly a month.

The truth about art theft in Europe – and Clerville is, among other things, a microcosm, or quintessence, of Europe – is less swashbuckling than most fiction. The exhibition halls at the Palazzo del Quirinale, spacious, sparsely decorated and a little flyblown, are exactly the sort of place where you can imagine Diabolik pulling off a caper, disguising himself as the President, say, or floating through the window on a jetpack. But the works on show in a minor blockbuster earlier this summer, all of it recovered by the TPC, had undergone various indignities that you’d struggle to turn into any kind of entertainment beyond a snuff movie. One masterpiece, a Hellenistic table support from Puglia in painted marble, representing two griffins lunching on a stag, had been hammered into pieces so it could be smuggled out of the country with a consignment of building materials. Three post-Impressionist paintings, smashed and grabbed from the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna twenty-one years ago, were destined for the bonfire, our guide said, if they couldn’t be consigned to their intended buyer. The “Senigallia Madonna” by Piero della Francesca, taken from the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino in 1975, was the subject of television appeals, like any kidnapping victim: “Please don’t touch her with your bare hands.” A stately, plump rococo cabinet had been cut down to fit a smaller space than that from which it had been untimely ripped.

The truth about art theft in Europe – and Clerville is, among other things, a microcosm, or quintessence, of Europe – is less swashbuckling than most fiction. The exhibition halls at the Palazzo del Quirinale, spacious, sparsely decorated and a little flyblown, are exactly the sort of place where you can imagine Diabolik pulling off a caper, disguising himself as the President, say, or floating through the window on a jetpack. But the works on show in a minor blockbuster earlier this summer, all of it recovered by the TPC, had undergone various indignities that you’d struggle to turn into any kind of entertainment beyond a snuff movie. One masterpiece, a Hellenistic table support from Puglia in painted marble, representing two griffins lunching on a stag, had been hammered into pieces so it could be smuggled out of the country with a consignment of building materials. Three post-Impressionist paintings, smashed and grabbed from the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna twenty-one years ago, were destined for the bonfire, our guide said, if they couldn’t be consigned to their intended buyer. The “Senigallia Madonna” by Piero della Francesca, taken from the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino in 1975, was the subject of television appeals, like any kidnapping victim: “Please don’t touch her with your bare hands.” A stately, plump rococo cabinet had been cut down to fit a smaller space than that from which it had been untimely ripped. The contrast could not have been starker—here was one of the world’s most revered figures, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, expressing his belief that all life is sentient, while I, as a card-carrying neuroscientist, presented the contemporary Western consensus that some animals might, perhaps, possibly, share the precious gift of sentience, of conscious experience, with humans. The setting was a symposium between Buddhist monk-scholars and Western scientists in a Tibetan monastery in Southern India, fostering a dialogue in physics, biology, and brain science. Buddhism has philosophical traditions reaching back to the fifth century B.C. It defines life as possessing heat (i.e., a metabolism) and sentience, that is, the ability to sense, to experience, and to act. According to its teachings, consciousness is accorded to all animals, large and small—human adults and fetuses, monkeys, dogs, fish, and even lowly cockroaches and mosquitoes. All of them can suffer; all their lives are precious.

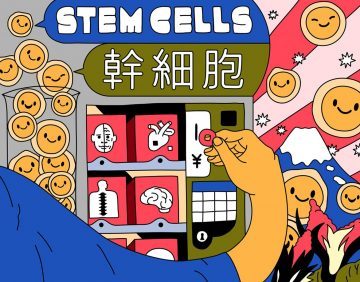

The contrast could not have been starker—here was one of the world’s most revered figures, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, expressing his belief that all life is sentient, while I, as a card-carrying neuroscientist, presented the contemporary Western consensus that some animals might, perhaps, possibly, share the precious gift of sentience, of conscious experience, with humans. The setting was a symposium between Buddhist monk-scholars and Western scientists in a Tibetan monastery in Southern India, fostering a dialogue in physics, biology, and brain science. Buddhism has philosophical traditions reaching back to the fifth century B.C. It defines life as possessing heat (i.e., a metabolism) and sentience, that is, the ability to sense, to experience, and to act. According to its teachings, consciousness is accorded to all animals, large and small—human adults and fetuses, monkeys, dogs, fish, and even lowly cockroaches and mosquitoes. All of them can suffer; all their lives are precious. Tucked away in Tokyo’s trendiest fashion district — two floors above a pricey French patisserie, and alongside nail salons and jewellers — the clinicians at Helene Clinic are infusing people with stem cells to treat cardiovascular disease. Smartly dressed female concierges with large bows on their collars shuttle Chinese medical tourists past an aquarium and into the clinic’s examination rooms.

Tucked away in Tokyo’s trendiest fashion district — two floors above a pricey French patisserie, and alongside nail salons and jewellers — the clinicians at Helene Clinic are infusing people with stem cells to treat cardiovascular disease. Smartly dressed female concierges with large bows on their collars shuttle Chinese medical tourists past an aquarium and into the clinic’s examination rooms. Since the upheavals of the financial crisis of 2008 and the political turbulence of 2016, it has become clear to many that liberalism is, in some sense, failing. The turmoil has given pause to economists, some of whom responded by renewing their study of inequality, and to political scientists, who have since turned to problems of democracy, authoritarianism, and populism in droves. But Anglo-American liberal political philosophers have had less to say than they might have.

Since the upheavals of the financial crisis of 2008 and the political turbulence of 2016, it has become clear to many that liberalism is, in some sense, failing. The turmoil has given pause to economists, some of whom responded by renewing their study of inequality, and to political scientists, who have since turned to problems of democracy, authoritarianism, and populism in droves. But Anglo-American liberal political philosophers have had less to say than they might have. Using a processor with programmable superconducting qubits, the Google team was able to run a computation in 200 seconds that they estimated the fastest supercomputer in the world would take 10,000 years to complete.

Using a processor with programmable superconducting qubits, the Google team was able to run a computation in 200 seconds that they estimated the fastest supercomputer in the world would take 10,000 years to complete. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to learn that when Google

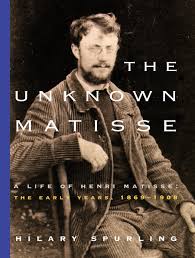

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to learn that when Google  Even those of us who have loved Matisse’s work since we began to look at paintings as a serious interest could not have suspected what it had cost this great artist to persevere in his vocation. Pleasure had so often been invoked as the key to an understanding of his achievement—“Un nom qui rime avec Nice . . . peintre du plaisir, sultan de Riviera, hédoniste raffiné,” as Pierre Schneider sardonically described this mistaken characterization of Matisse—that it has come as a shock to discover the sheer scale of adversity that had to be endured at almost every stage of his life and work.

Even those of us who have loved Matisse’s work since we began to look at paintings as a serious interest could not have suspected what it had cost this great artist to persevere in his vocation. Pleasure had so often been invoked as the key to an understanding of his achievement—“Un nom qui rime avec Nice . . . peintre du plaisir, sultan de Riviera, hédoniste raffiné,” as Pierre Schneider sardonically described this mistaken characterization of Matisse—that it has come as a shock to discover the sheer scale of adversity that had to be endured at almost every stage of his life and work. If at the beginning of the crisis in Hong Kong, three months ago, it was hard for some to imagine how a supposedly democratic conclave within authoritarian China and the pride of imperial capitalists everywhere would soon become the undeclared police state it now is, it’s an even bigger challenge to imagine how the political crisis might be resolved without a dramatic redefinition of the relationship between the semi-autonomous territory and Beijing’s dictatorial central government. The movement—the revolution, the rebellion, the resistance, the terrorism, the uprising, whatever it is called, depending on who you ask—started as a protest against

If at the beginning of the crisis in Hong Kong, three months ago, it was hard for some to imagine how a supposedly democratic conclave within authoritarian China and the pride of imperial capitalists everywhere would soon become the undeclared police state it now is, it’s an even bigger challenge to imagine how the political crisis might be resolved without a dramatic redefinition of the relationship between the semi-autonomous territory and Beijing’s dictatorial central government. The movement—the revolution, the rebellion, the resistance, the terrorism, the uprising, whatever it is called, depending on who you ask—started as a protest against  This new “Darkness at Noon” arrives in a very different world from that which greeted the original, and one important difference has to do with Koestler’s reputation. In 1940, he was thirty-five and little known in the English-speaking world. He had been a successful journalist in Berlin and a Communist Party activist in Paris, but “Darkness at Noon” was his first published novel. It transformed him from a penniless refugee into a wealthy and famous man, and was also the best book he would ever write. It was followed, in the forties, by an important book of essays, “The Yogi and the Commissar,” and several thought-provoking but less consequential novels of politics and ideas, including “Arrival and Departure,” which reckoned with Freudianism, and “Thieves in the Night,” about Jewish settlers in Palestine.

This new “Darkness at Noon” arrives in a very different world from that which greeted the original, and one important difference has to do with Koestler’s reputation. In 1940, he was thirty-five and little known in the English-speaking world. He had been a successful journalist in Berlin and a Communist Party activist in Paris, but “Darkness at Noon” was his first published novel. It transformed him from a penniless refugee into a wealthy and famous man, and was also the best book he would ever write. It was followed, in the forties, by an important book of essays, “The Yogi and the Commissar,” and several thought-provoking but less consequential novels of politics and ideas, including “Arrival and Departure,” which reckoned with Freudianism, and “Thieves in the Night,” about Jewish settlers in Palestine.

“Plato once defined humans as featherless bipeds, but he didn’t know about dinosaurs, kangaroos, and meerkats. In actual fact, we humans are the only striding, featherless, and tailless bipeds. Even so, tottering about on two legs has evolved only a few times, and there are no other bipeds that resemble humans, making it hard to evaluate the comparative advantages and disadvantages of being a habitually upright hominin. If hominin bipedalism is so exceptional, why did it evolve? And how did this strange manner of standing and walking influence subsequent evolutionary changes to the hominin body?

“Plato once defined humans as featherless bipeds, but he didn’t know about dinosaurs, kangaroos, and meerkats. In actual fact, we humans are the only striding, featherless, and tailless bipeds. Even so, tottering about on two legs has evolved only a few times, and there are no other bipeds that resemble humans, making it hard to evaluate the comparative advantages and disadvantages of being a habitually upright hominin. If hominin bipedalism is so exceptional, why did it evolve? And how did this strange manner of standing and walking influence subsequent evolutionary changes to the hominin body? Eight years ago, Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote

Eight years ago, Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote

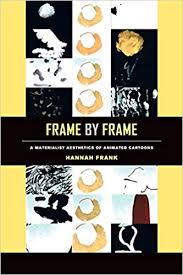

IT’S NOT EVERY DAY that a posthumously published Ph.D. thesis nudges the world of cinema studies off its axis. All hail Frame by Frame: A Materialist Aesthetics of Animated Cartoons (2019), by Hannah Frank, who completed the book shortly before her tragic death in 2017, at age thirty-two, from an illness believed to have been pneumococcal meningitis.

IT’S NOT EVERY DAY that a posthumously published Ph.D. thesis nudges the world of cinema studies off its axis. All hail Frame by Frame: A Materialist Aesthetics of Animated Cartoons (2019), by Hannah Frank, who completed the book shortly before her tragic death in 2017, at age thirty-two, from an illness believed to have been pneumococcal meningitis. Sontag emerges less as the heir to intellectual crusaders such as Hannah Arendt or Mary McCarthy than the better-educated cousin of the wily and preening Gore Vidal – another victim of an abusive single mother who was obsessed with renown and recognition, unable to identify as homosexual, and took cover behind a persona largely created in the New York Review of Books. Where Vidal’s contemporary Norman Mailer once hoped that he would go deeper into himself and turn “the prides of his detachment into new perception”, the feminist poet Adrienne Rich wrote of Sontag that “one is simply eager to see this woman’s mind working out of a deeper complexity, informed by emotional grounding”.

Sontag emerges less as the heir to intellectual crusaders such as Hannah Arendt or Mary McCarthy than the better-educated cousin of the wily and preening Gore Vidal – another victim of an abusive single mother who was obsessed with renown and recognition, unable to identify as homosexual, and took cover behind a persona largely created in the New York Review of Books. Where Vidal’s contemporary Norman Mailer once hoped that he would go deeper into himself and turn “the prides of his detachment into new perception”, the feminist poet Adrienne Rich wrote of Sontag that “one is simply eager to see this woman’s mind working out of a deeper complexity, informed by emotional grounding”. We had our fun last week, exploring how progress in renewable energy and electric vehicles may help us combat encroaching climate change. This week we’re being a bit more hard-nosed, taking a look at what’s currently happening to our climate. Michael Mann is one of the world’s leading climate scientists, and also a dedicated advocate for improved public understanding of the issues. It was his research with Raymond Bradley and Malcolm Hughes that introduced the “hockey stick” graph, showing how global temperatures have increased rapidly compared to historical averages. We dig a bit into the physics behind the greenhouse effect, the methods that are used to reconstruct temperatures in the past, how the climate has consistently been heating up faster than the average models would have predicted, and the relationship between climate change and extreme weather events. Happily even this conversation is not completely pessimistic — if we take sufficiently strong action now, there’s still time to avert the worst possible future catastrophe.

We had our fun last week, exploring how progress in renewable energy and electric vehicles may help us combat encroaching climate change. This week we’re being a bit more hard-nosed, taking a look at what’s currently happening to our climate. Michael Mann is one of the world’s leading climate scientists, and also a dedicated advocate for improved public understanding of the issues. It was his research with Raymond Bradley and Malcolm Hughes that introduced the “hockey stick” graph, showing how global temperatures have increased rapidly compared to historical averages. We dig a bit into the physics behind the greenhouse effect, the methods that are used to reconstruct temperatures in the past, how the climate has consistently been heating up faster than the average models would have predicted, and the relationship between climate change and extreme weather events. Happily even this conversation is not completely pessimistic — if we take sufficiently strong action now, there’s still time to avert the worst possible future catastrophe.