Quinn Slobodian in The Guardian:

Quinn Slobodian in The Guardian:

Two of the “freest economies” in the world are on fire. According to indexes of “economic freedom” published annually separately by two conservative thinktanks – the Heritage Foundation and the Fraser Institute – Hong Kong has been number one in the rankings for more than 20 years. Chile is ranked first in Latin America by both indexes, which also place it above Germany and Sweden in the global league table.

Violent protest in Hong Kong has entered its eighth month. The target is Beijing, but the lack of universal suffrage that is catalysing popular anger has long been part of Hong Kong’s economic model. In Chile, where student-led protests against a rise in subway fares turned into a nationwide anti-government movement, the death toll is at least 18.

The rage may be better explained by other rankings: Chile places in the top 25 for economic freedom – and also for income inequality. If Hong Kong were a country, it would be in the world’s top 10 most unequal. Observers often use the word neoliberalism to describe the policies behind this inequality. The term can seem vague, but the ideas behind the economic freedom index help to bring it into focus.

All rankings hold visions of utopia within them. The ideal world described by these indexes is one where property rights and security of contract are the highest values, inflation is the chief enemy of liberty, capital flight is a human right and democratic elections may work actively against the maintenance of economic freedom.

More here.

Mistress Snow in The Chronicle Review:

Mistress Snow in The Chronicle Review: B

B Reading The Dry Heart is like listening to a person confess in half-truths. The second time the narrator revisits killing Alberto, she describes how she prepared him a thermos of tea with milk and sugar before pulling his revolver out of his desk. The third time, she reveals that he was packing his bags for a trip; that she suspected he was not traveling alone; and that when she told him she would “rather know the truth, whatever it may be,” he replied by misquoting Dante’s Purgatorio: “She seeketh Truth, which is so dear / As knoweth he who life for her refuses.”

Reading The Dry Heart is like listening to a person confess in half-truths. The second time the narrator revisits killing Alberto, she describes how she prepared him a thermos of tea with milk and sugar before pulling his revolver out of his desk. The third time, she reveals that he was packing his bags for a trip; that she suspected he was not traveling alone; and that when she told him she would “rather know the truth, whatever it may be,” he replied by misquoting Dante’s Purgatorio: “She seeketh Truth, which is so dear / As knoweth he who life for her refuses.” I

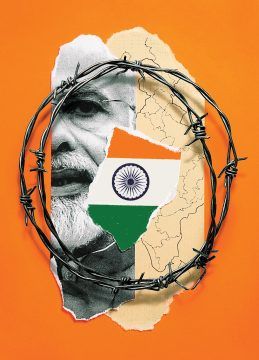

I In August of this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India suspended Article 370 of the constitution, the provision that granted some level of autonomy to

In August of this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India suspended Article 370 of the constitution, the provision that granted some level of autonomy to  Englishness was always a form of theatre, first staged in overseas colonies. Discovering its traces in Rudyard Kipling and India, VS Naipaul remarked on how, “at the height of their power, the British gave the impression of a people at play, a people playing at being English, playing at being English of a certain class”. Today, in a post-imperial Britain run by half-witted public schoolboys, the English character seems even more, as Naipaul wrote, “a creation of fantasy”.

Englishness was always a form of theatre, first staged in overseas colonies. Discovering its traces in Rudyard Kipling and India, VS Naipaul remarked on how, “at the height of their power, the British gave the impression of a people at play, a people playing at being English, playing at being English of a certain class”. Today, in a post-imperial Britain run by half-witted public schoolboys, the English character seems even more, as Naipaul wrote, “a creation of fantasy”. We’re on Flatey, a small island in an archipelago in West Iceland. These islands are clustered in Breiðafjörður, a fjord that Icelanders often talk about in metaphorical terms: “Their freckles were as countless as the islands in Breiðafjörður.” We write this in June, when the sun never forsakes the sky, and half of the island is closed off because it’s nesting season. There are birds everywhere.

We’re on Flatey, a small island in an archipelago in West Iceland. These islands are clustered in Breiðafjörður, a fjord that Icelanders often talk about in metaphorical terms: “Their freckles were as countless as the islands in Breiðafjörður.” We write this in June, when the sun never forsakes the sky, and half of the island is closed off because it’s nesting season. There are birds everywhere. This reliance on models has always been a bête noire for climate change deniers, who have questioned their accuracy as a way of casting doubt on their dire projections. For years, it has been a running battle between scientists and their critics, with the former rallying to defend one dataset and model after another. (The invaluable site Skeptical Science has a

This reliance on models has always been a bête noire for climate change deniers, who have questioned their accuracy as a way of casting doubt on their dire projections. For years, it has been a running battle between scientists and their critics, with the former rallying to defend one dataset and model after another. (The invaluable site Skeptical Science has a  On August 11th, two weeks after Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent soldiers in to pacify the Indian state of Kashmir, a reporter appeared on the news channel Republic TV, riding a motor scooter through the city of Srinagar. She was there to assure viewers that, whatever else they might be hearing, the situation was remarkably calm. “You can see banks here and commercial complexes,” the reporter, Sweta Srivastava, said, as she wound her way past local landmarks. “The situation makes you feel good, because the situation is returning to normal, and the locals are ready to live their lives normally again.” She conducted no interviews; there was no one on the streets to talk to.

On August 11th, two weeks after Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent soldiers in to pacify the Indian state of Kashmir, a reporter appeared on the news channel Republic TV, riding a motor scooter through the city of Srinagar. She was there to assure viewers that, whatever else they might be hearing, the situation was remarkably calm. “You can see banks here and commercial complexes,” the reporter, Sweta Srivastava, said, as she wound her way past local landmarks. “The situation makes you feel good, because the situation is returning to normal, and the locals are ready to live their lives normally again.” She conducted no interviews; there was no one on the streets to talk to. Wood points out that contemporary image-based culture — the profusion he can barely sum up by listing “advertising, fashion, celebrities, television, tattoos, toys, comics, pornography, politics, iPhones, and stuff in general” — is impossible for art history to grasp, even though it is to a great extent the content of contemporary art. But his belief that today’s art “is no longer preoccupied with form” is one that would hardly be accepted by most artists or anyone else who is involved in contemporary art on a daily basis.

Wood points out that contemporary image-based culture — the profusion he can barely sum up by listing “advertising, fashion, celebrities, television, tattoos, toys, comics, pornography, politics, iPhones, and stuff in general” — is impossible for art history to grasp, even though it is to a great extent the content of contemporary art. But his belief that today’s art “is no longer preoccupied with form” is one that would hardly be accepted by most artists or anyone else who is involved in contemporary art on a daily basis. Pathetically little has improved for menopausal women since Wilson died in 1981. Our fears, degradations, and inequalities are still blamed on us—and are still well-used by corporate pill-pushers. Pharmaceutical industry watchers estimate that by 2022, the HRT market will be worth an estimated $28.4 billion. (By comparison, the annual revenue of one of the top ten pharmaceutical companies in the world, Johnson & Johnson, is $40 billion.)

Pathetically little has improved for menopausal women since Wilson died in 1981. Our fears, degradations, and inequalities are still blamed on us—and are still well-used by corporate pill-pushers. Pharmaceutical industry watchers estimate that by 2022, the HRT market will be worth an estimated $28.4 billion. (By comparison, the annual revenue of one of the top ten pharmaceutical companies in the world, Johnson & Johnson, is $40 billion.) “Mary MacLane is mad,” wrote the New York Herald. “She should be put under medical treatment, and pens and paper kept out of her way until she is restored to reason.” The New York Times urged that she be spanked. Other critics raised the charge of “obscenity.” When the Butte Public Library announced that it would not allow the book on its shelves, the Helena Daily Independent applauded, arguing that if this book “should go in, all the self-respecting books in the library would jump out of the window.”

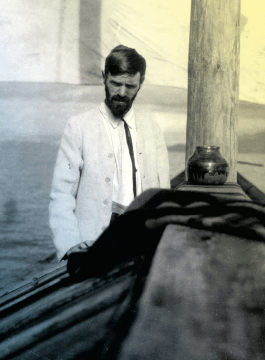

“Mary MacLane is mad,” wrote the New York Herald. “She should be put under medical treatment, and pens and paper kept out of her way until she is restored to reason.” The New York Times urged that she be spanked. Other critics raised the charge of “obscenity.” When the Butte Public Library announced that it would not allow the book on its shelves, the Helena Daily Independent applauded, arguing that if this book “should go in, all the self-respecting books in the library would jump out of the window.” My relationship with D. H. Lawrence began in high school, when I bought a copy of Sons and Lovers more or less at random and proceeded to read it all the way through, by which I mean that my eyes literally traversed every page and recognized that the English language was there recorded in some complexity. But the words, instead of building a reality I could enter and move around in, were like a continually dying fluorescence. I had no idea what was going on. What registered was something like “words, words, flower, sentence, words, coal mining” (like I knew what a coal mine was). As far as I was concerned, Sons and Lovers appeared out of nothing and to nothing it returned. All I knew when I was finished was all I knew before I plucked it, more or less at random, off the shelf: that it was a “classic.”

My relationship with D. H. Lawrence began in high school, when I bought a copy of Sons and Lovers more or less at random and proceeded to read it all the way through, by which I mean that my eyes literally traversed every page and recognized that the English language was there recorded in some complexity. But the words, instead of building a reality I could enter and move around in, were like a continually dying fluorescence. I had no idea what was going on. What registered was something like “words, words, flower, sentence, words, coal mining” (like I knew what a coal mine was). As far as I was concerned, Sons and Lovers appeared out of nothing and to nothing it returned. All I knew when I was finished was all I knew before I plucked it, more or less at random, off the shelf: that it was a “classic.” One hundred and twenty million years ago, when northeastern China was a series of lakes and erupting volcanoes, there lived a tiny mammal just a few inches long. When it died, it was

One hundred and twenty million years ago, when northeastern China was a series of lakes and erupting volcanoes, there lived a tiny mammal just a few inches long. When it died, it was  This generous collection of 154 pieces of what Brian Boyd in the introduction calls Nabokov’s ‘public prose’ – mostly uncollected and sometimes also unpublished journalism – is presented chronologically. Where necessary, the pieces have been expertly translated from Russian and French by Boyd and Anastasia Tolstoy, and the notes and index make this book easy to negotiate. The text is marred only by a few idiosyncratic transliterations of Russian words. At first sight, the book may seem to be yet more of those scrapings from the barrel that have been served up over the four decades since Nabokov’s death. However, unlike the embarrassingly jejune fragments of his novels, such as The Original of Laura, that have been published posthumously, this collection includes some of his sharpest prose, as well as his most cursory. It spans Nabokov’s career, from juvenilia to senilia. In Germany, where Nabokov is revered enough for Rowohlt to have published his collected works in twenty-five volumes, a similar anthology of the author’s ‘public prose’ came out fifteen years ago with the title Eigensinnige Ansichten (probably best translated as ‘Stubbornly Held Views’ or ‘Prejudices’). Stubbornness, even perversity, certainly underlies Nabokov’s opinions.

This generous collection of 154 pieces of what Brian Boyd in the introduction calls Nabokov’s ‘public prose’ – mostly uncollected and sometimes also unpublished journalism – is presented chronologically. Where necessary, the pieces have been expertly translated from Russian and French by Boyd and Anastasia Tolstoy, and the notes and index make this book easy to negotiate. The text is marred only by a few idiosyncratic transliterations of Russian words. At first sight, the book may seem to be yet more of those scrapings from the barrel that have been served up over the four decades since Nabokov’s death. However, unlike the embarrassingly jejune fragments of his novels, such as The Original of Laura, that have been published posthumously, this collection includes some of his sharpest prose, as well as his most cursory. It spans Nabokov’s career, from juvenilia to senilia. In Germany, where Nabokov is revered enough for Rowohlt to have published his collected works in twenty-five volumes, a similar anthology of the author’s ‘public prose’ came out fifteen years ago with the title Eigensinnige Ansichten (probably best translated as ‘Stubbornly Held Views’ or ‘Prejudices’). Stubbornness, even perversity, certainly underlies Nabokov’s opinions. Mosquitoes. Hordes of them, buzzing in your ear and biting incessantly, a maddening nuisance without equal. And not to mention the devastating health impacts caused by malaria, Zika virus and other pathogens they spread.

Mosquitoes. Hordes of them, buzzing in your ear and biting incessantly, a maddening nuisance without equal. And not to mention the devastating health impacts caused by malaria, Zika virus and other pathogens they spread. In

In